Incitement & Terrorism

Incitement and terrorism have been a longstanding concern and a source of tension between Israelis and Palestinians. Typically raised by Israeli leaders, and Israel’s supporters in the U.S., incitement is commonly understood as a form of extreme hate speech and discourse that promotes and encourages violence and terrorism, or even the denial of Israel’s right to exist.

When almost 3,000 Hamas militants and numerous Gazan civilians broke through the security barrier and murdered almost 800 civilians and 400 Israeli security forces, injured another 3,400, and kidnapped 247, many Israelis and others abroad were reminded of the dangers of incitement and terrorism. Though the events of October 7th were not a spontaneous act of popular aggression, but rather a calculated Hamas military operation, the positive reception in Palestinian society to the Hamas attack reflected a deeply entrenched culture of incitement that promotes terrorism. A poll conducted in December 2023 found that 72% of Palestinians supported Hamas’ attack on October 7th. This percentage has held steady – a poll in March 2024 found a similar result (71%).

When Israel provided allegations that UNRWA employees were involved in or supported the attack, the US, Germany, and at least a dozen other countries declared they would pause funding to UNRWA. Furthermore, watchdog organization IMPACT-se (Israeli Institute for Monitoring Peace and Cultural Tolerance in School Education) reported that the events of October 7th have been celebrated in several Palestinian schools in the West Bank and Gaza.

Likewise, Israeli rhetoric surrounding the current war has been problematic for Palestinians including several statements from prominent Israeli politicians. These comments were at the core of South Africa’s accusation that Israel was committing genocide that the country brought to the International Court Justice in late 2023. For many Israelis, however, these claims were akin to a blood libel focusing on the victims, rather than the perpetrators, of a massive terror attack.

There has also been increased pressure from the Biden administration to clamp down on Israeli settlements that are often the origin of attacks on Palestinians and the administration implemented sanctions targeted against settlements, individuals, and organizations that were promoting violence against Palestinians. These U.S. sanctions have been followed by sanctions by the United Kingdom and France in an effort to curb extremist violence.

Yesha Council map of Israel

Map of Palestine (Egypt Logo Center)

Left: Yesha Council map of Israel

Right: Map of Palestine (Egypt Logo Center)

Examples of Incitement

The most common charge of incitement focuses on official statements or content generated by government or political party-sponsored media. For example, as part of the Oslo process, Palestinian leaders committed to forswear violence and recognize Israel, though it was not long before charges of incitement began to seep into bilateral relations.

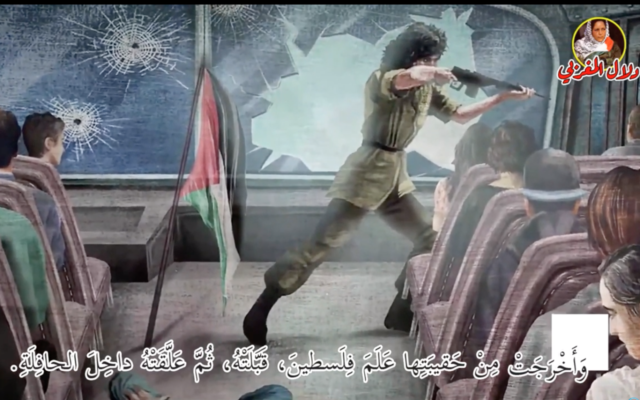

Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat often invoked Palestinian “martyrs” or called for “jihad,” rhetoric Israelis considered incitement. In a more recent example, Palestinian officials honored Dalal Mugrabi, one of the masterminds of a notorious terrorist attack in Israel in 1978 in which dozens of Israeli civilians were killed, including children. Some Palestinian leaders and civil society figures, including the late Faisal Husseini, have called for the “liberation” of Palestine from “the river to the sea,” rhetoric Israelis consider incitement.1 See “Mystery surrounds Faisal Husseini’s Last Interview,” Danny Rubinstein, Haaretz, https://www.haaretz.com/1.5344834

The PLO’s official insignia includes a map of “Palestine,” which does not include Israel, and the Fatah party—the most important Palestinian political party within the PLO and President Abbas’ political home—has rifles in its crest. Many Israelis consider these symbols to be a form of incitement.

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) Logo

Fatah Flag

Left: The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) Logo

Right: Fatah Flag

Beyond the government and recognized Palestinian authorities, there are further concerns about incitement that are regularly raised. Palestinian extremist and terrorist groups, like Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad, are regular sources of incitement to violence via statements of their leaders and media outlets.

U.N. social service agencies, like UNRWA, also receive criticism for allowing incitement and hate speech from their platforms or via their educational institutions—though the U.N. rejects such charges, pointing to their own corrective measures and to U.S. and member state oversight. Attempts have been made to cut U.S. and EU funding to UNRWA in part because of accusations of incitement in UNRWA schools. In 2018, the Trump administration cut funding to UNRWA though the Biden administration resumed it. However, in the aftermath of October 7th, Israel provided allegations that UNRWA employees were involved in or supported the attack. As a result, the U.S., Germany, and at least a dozen other countries declared they would pause funding to UNRWA. In the FY2024 funding bill UNRWA funding was banned for one calendar year (March 25th 2025).

More broadly, there is criticism that incitement is rampant in Palestinian social, popular and mass media.2 There is also vociferous condemnation of what critics call “pay to slay,” the practice of payments to the families of Palestinians who commit acts of violence and terrorism. Palestinian leaders would be wise to tackle this issue in a more serious and transparent manner and put an end to payments that directly benefit perpetrators of terrorism.

Sen. Lindsey Graham on Capitol Hill with Stuart and Robbi Force of South Carolina (Mary Troyan/Greenville News, 2016)

PALESTINIAN RESPONSES

Palestinian leaders have generally rejected criticisms about incitement, pointing to their repeated, official condemnations of violence, and the intense oversight and scrutiny of the international donor community for nearly three decades. Avoiding censorship or protecting freedom of expression are also common responses.

Palestinians will often respond to charges of incitement by pointing to Israeli attacks, like the mass killing of Palestinian worshippers in 1994 in Hebron, the horrific murder of Palestinian teenager Muhammed Abu Khdeir in 2014, or the arson-murder of the Dawabshe family in Duma the following year. Palestinians also cite ‘price-tag’ attacks by Israeli “Hill Top Youth” as ongoing examples of incitement and violence.

Moreover, Palestinian leaders sometimes dismiss concerns about incitement, claiming the arguments are made by Israelis who are against peacemaking and are looking for a convenient excuse to avoid compromise.

DIPLOMATIC AND POLICY RESPONSES

Policymakers have struggled for years to turn concerns about incitement into clearly defined standards and effective policy solutions.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his then-Foreign Minister, the late Ariel Sharon, put a particular emphasis on the issue at the 1998 Wye River Peace Accords. They managed to achieve two concessions from the Palestinians. First, Arafat convened the Palestinian National Council which voted to amend the PLO official charter, canceling provisions calling for “armed struggle,” further reinforcing the Palestinian commitment to forswear violence.

Second, the U.S. supported the establishment of a trilateral U.S.-Israel-Palestinian “anti-incitement” committee, which was compsed of experts and met for 1-2 years, though the body was unable to produce any meaningful outcomes. In fact, the work of the committee laid bare that the parties could not agree on a definition of incitement or what specifically should be done about it.

Signing ceremony of the Wye River peace accords (Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 1998)

Still, Israeli leaders have continued to raise the concern regularly—in terms of official Palestinian Authority actions, statements and actions by other Palestinian actors, and also in the context of U.N. supported educational and social programs—and the U.S. and the international community regularly repeat these concerns, though little concrete action has been proposed in recent years.2 See Jerusalem Post, “UN Expresses Rare Criticism on Palestinian Hate Speech and Incitement,” for a report on the 2019 report of the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

American leaders, both Democrats and Republicans, have regularly spoken out against incitement. After a horrific attack on Jewish worshippers at a synagogue in Jerusalem in 2014, Secretary of State John Kerry condemned “incitement…(and) calls for ‘days of rage…(which are) unacceptable.”3 See https://apnews.com/dc225aa303c94ae9bebde273ce3764bb/john-kerry-condemns-attack-jerusalem- synagogue, November, 2014. President Trump has raised the issue repeatedly, calling on Palestinians to “speak in a unified voice against incitement to violence and hate” when he first met with PA President Abbas in Washington. In releasing his peace plan in January 2020, Trump called for “ending the incitement of hatred against Israel.”

Although Israeli leaders gave less priority in the past to the PA’s “welfare” payments, following the passage of the Taylor Force Act in 2018—named for an American graduate student and military veteran who was murdered by a Palestinian terrorist in Tel Aviv in 2016—direct U.S. government economic assistance to the Palestinian Authority was suspended unless and until Palestinian officials end such payments.

Israel passed a similar law aimed at curtailing “pay to slay,” which allows Israel to withhold and deduct the amount of money the PA provides in such payments from the taxes and tariffs Israel collects on the PA’s behalf.

Making it clear that there are no official PA policies that incentivize violence is critical to building trust and restoring faith in Palestinian governing institutions. Exclusively employing income-based and other acceptable formulas to establish eligibility for social welfare programs could effectively decouple violent acts and payments and preserve much-needed social and economic safety nets.

Still, money is fungible and experts concede that there is no ironclad way for either the U.S. or Israel to put in place a total ban on problematic payments. That said, there is more the U.S., Israel and other parties could do to report on this issue, generate greater transparency, and encourage other donors, including in Europe and among Arab states, to adopt measures that make it more difficult to use international assistance for such condemnable behavior. For example, the EU Parliament has passed resolutions every year since 2019 criticizing the PA for its textbook contents which often contain imagery glorifying martyrdom. Though these resolutions were backed with threats to cut funding there has been little follow-through.

Even here, Palestinians will defend their decisions about social welfare policies, saying allowances to families of “martyrs,” the wounded, or prisoners represent a larger ideal of defending their right of self-determination under conditions they deem to be occupation.

Many anti-incitement watchdogs and experts call for greater educational efforts and counter speech as a strategy for combating incitement. Still, some experts say such efforts can backfire. For example, “when Arabs hear stories of the Holocaust, or Israelis confront reports of historical Palestinian suffering…they resent the accounts as instruments intended to elicit sympathy or weaken their will.4 See Shibley Telhami, Brookings Institution, 2014, https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/the-power-and-weakness- of-inciting-violence/

A group of Palestinian students visit to Auschwitz (Moment, 2014)

Digging Deeper

”Jewish Settler Violence Increasing in West Bank” Voice of America

*These materials are provided for reference purposes, with no intention of endorsement.