Right of Return & Refugees

The Palestinian refugee problem is one of the thorniest topics the parties have faced, at times contributing to the breakdown of negotiations. The vast majority of Palestinians in the world, including large numbers of those in Gaza, the West Bank and East Jerusalem consider themselves and their families to be refugees. In fact, Palestinian identity is deeply intertwined with refugee status and the notion of being displaced.

As part of the 1993 Oslo Accords, for the first time Israelis and Palestinians agreed to negotiate a solution to the refugee problem. American leaders, including President Bill Clinton, have put forward compromise proposals, involving resettlement, compensation and absorption into a new Palestinian state, though none of the ideas have been accepted.

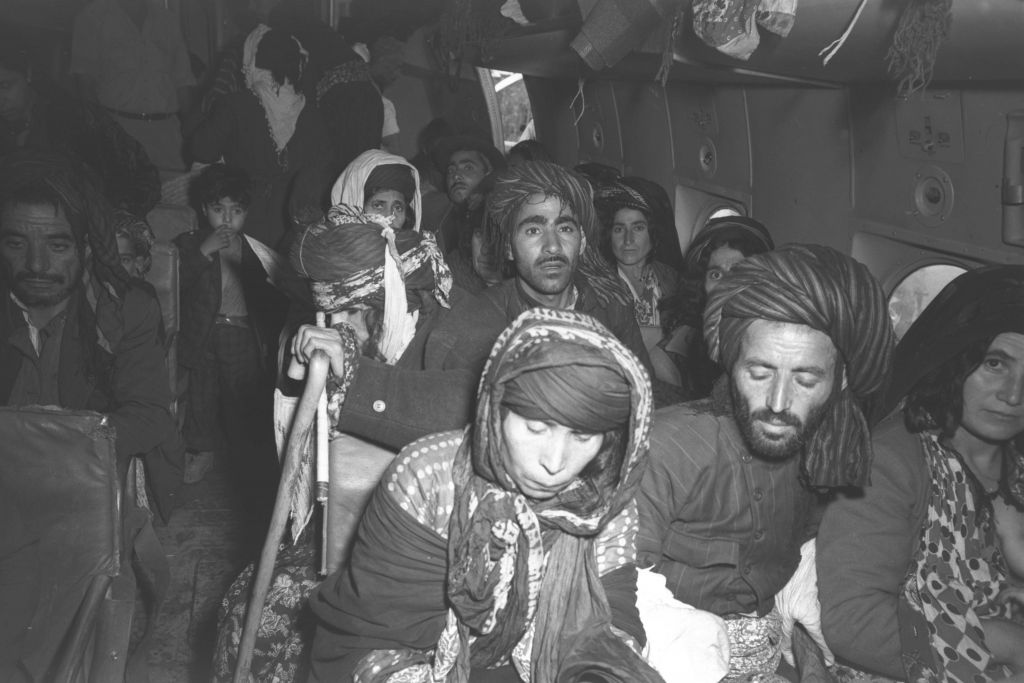

At the conclusion of the Arab-Israeli War of 1948-49, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians had left their homes and property within the new state of Israel. Israelis and Palestinians disagree profoundly about who is responsible for the situation and what should be done—they even disagree on the number of refugees. Although both sides have made some progress during negotiations on practical measures to ultimately address the needs of Palestinian refugees, the intense emotional and narrative aspects of the issue make it difficult to resolve.

October 7th Update

As of the beginning of February, 2024, satellite imaging analysis suggests that well over 50% of buildings in Gaza have been damaged or destroyed. With this widespread destruction, attention is starting to focus on what rebuilding might look like. Israeli decision-makers are keen to ensure what was before October 7th will not be repeated. Israel seeks to minimize or entirely eliminate the role of UNRWA in Gaza and elsewhere and see the war period and its aftermath as an opportunity to “resettle” the Gazans who remain in Gaza, but without them retaining their special refugee status. Palestinians perceive the war in Gaza as another Nakba and view Israeli policy and military strategy aimed at expelling large numbers of Palestinians from Gaza. While Israeli officials might claim that any transfer of population or decision to relocate to other countries is voluntary, Palestinians assert that the military operations have made much of Gaza uninhabitable in order to push Palestinians off their land.

QUESTION

Can there be a “just” resolution of the Palestinian refugee issue consistent with Israel’s identity and demographic concerns?

PALESTINIAN PERSPECTIVE

Palestinians frame the refugee issue in the context of justice, dignity, victimhood, and international law. At the core of the Palestinian narrative is the “Nakba” (“catastrophe”) — the 1948-49 war. Most Palestinians blame Israel for creating the Palestinian refugee situation, as part of a longstanding, disenfranchising Zionist policy from the early 20th century. They argue that during the war, Israel forced Palestinians from their homes. After the war ended and the armistice agreements were signed, Israel mostly blocked Palestinian refugees from returning, another factor Palestinians cite in asserting that Israel is primarily responsible for the plight of Palestinian refugees.

Another wave of Palestinian refugees was created by the 1967 War, and tens of thousands more in subsequent conflicts in Jordan, Lebanon and Syria.

Yarmouk, a Palestinian refugee camp in Damascus (UNRWA)

Palestinians demand a “right of return” to their lost homes and villages within the State of Israel. Although in most cases these homes no longer exist, many Palestinians express a deep desire to return, and still possess the original keys passed down through the generations. Encouraged by Palestinian leadership, the Nakba and the right of return (with a key as its most potent symbol) have become core features of Palestinian identity. According to the Palestinians and the United Nations, there were approximately 750,000 Palestinian refugees after the 1948 War, and the surviving refugees, their descendants and the refugees from subsequent wars now number seven million. The Palestinians argue that these descendants must be included in a resolution of the issue.

ISRAELI PERSPECTIVE

Most Israelis blame the Palestinians and Arab states for creating and perpetuating the Palestinian refugee situation. They note that Israel’s War of Independence from 1948-49 began when Arab states rejected the United Nations Partition Plan and attacked Israel, and that Palestinians either left their homes voluntarily or were encouraged to do so by the invading Arab armies, who expected a quick victory. Although there are a variety of historical accounts, the prevailing Israeli understanding is that displacement by force did not occur as an overall strategy, and to the extent that it did occur in specific situations, it was isolated or had legitimate wartime rationale.

Israeli perspective on Palestinian refugees

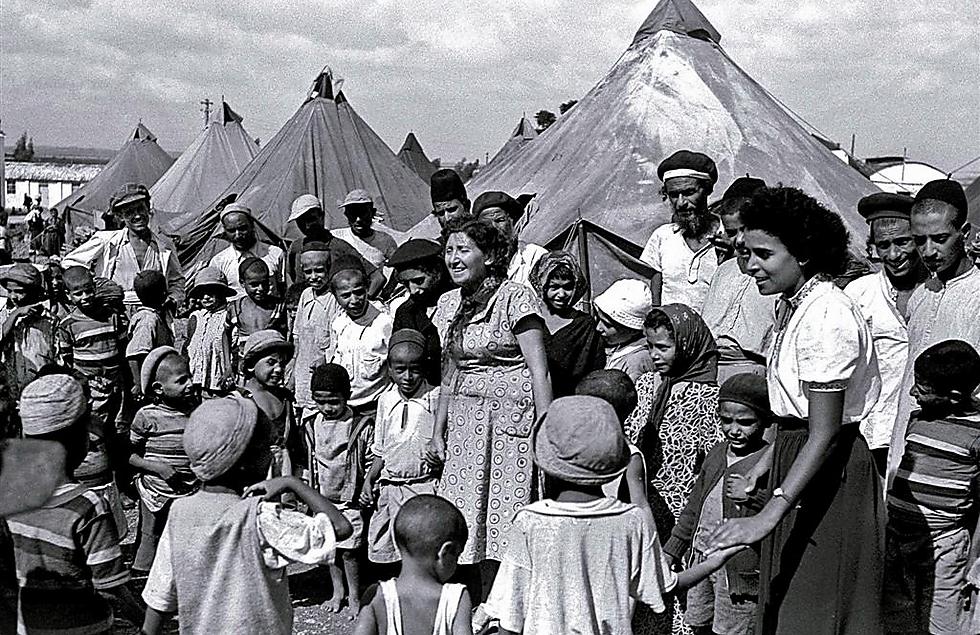

According to the Israeli perspective, Palestinian refugees have few or no legitimate claims against Israel. They accuse Palestinians of inflating the number of refugees, and (along with the Arab states and United Nations) exploiting the issue for political gain, needlessly creating new generations of refugees, instead of resettling them in other countries as other communities have done. Israelis reject the notion that the descendants of the 750,000 1948-49 refugees should be considered refugees themselves, and argue that no other refugee population enjoys a comparable “right of return” for subsequent generations. Israelis hold different interpretations of U.N. General Assembly Resolution 194 and international law and reject Palestinian return rights — both legally and practically.

Many Jews in Israel and the Diaspora also believe that if Palestinian refugees are to be compensated, then so should the reported 856,000 Jewish refugees from Arab states — whose lives were upended and assets were seized when they were forced to flee. Additionally, Israel argues that compensation should be internationally funded.

For Israelis, the possibility of millions of Palestinians moving to Israel through a ‘right of return’ would jeopardize, if not overturn, the Jewish majority in Israel that underpins its Jewish and democratic character and its status as the homeland of the Jewish people. To mitigate this possibility, and in the context of negotiations, Israel has demanded that Palestinians formally recognize the Jewish character of the state of Israel, and declare an end to the conflict and resolution of all claims.

UNRWA

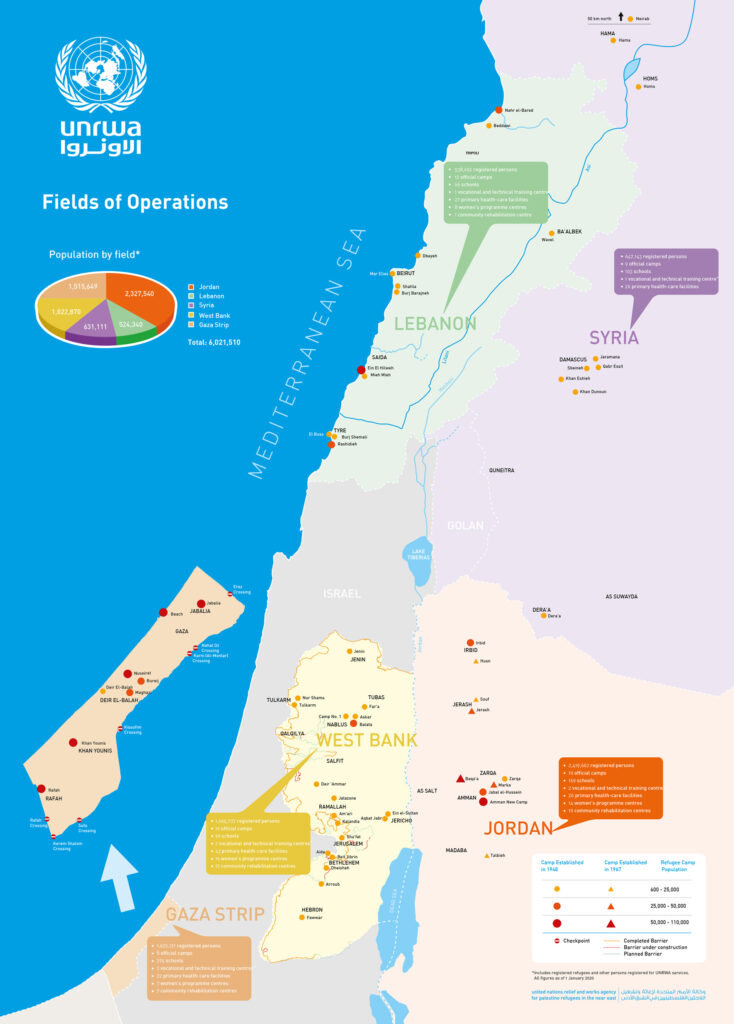

The United Nations Relief Works Agency (UNRWA) was established by the U.N. General Assembly in 1949 — in the wake of the first Arab-Israeli War— as a temporary humanitarian organization for Palestinian refugees. But, as the refugee issue has persisted over multiple generations, so has UNRWA’s work, providing education, health care, and other social services to over three million Palestinians in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria.

UNRWA logo (Wikimedia Commons)

Map of Palestinian refugee camps (UNRWA)

Left: UNRWA logo (Wikimedia Commons)

Right: Map of Palestinian refugee camps (UNRWA)

Over time, UNRWA’s activities have become intensely politicized. The Israeli government has long argued for UNRWA’s end, blaming it for perpetuating the refugee issue by extending refugee status to the millions of descendants of the original Palestinian refugees. Israelis contend that UNRWA has made Palestinians dependent on its social services, incited against Israel in its education materials, and even aided Hamas rockets during the 2014 Israel-Gaza War. UNRWA rejects these criticisms, noting that it is standard practice among refugee bodies to offer multi-generational refugee status. Additionally, UNRWA has condemned Hamas, which it accuses of exploiting its presence in Gaza. And defending its educational role, UNRWA notes that while it has traditionally relied on the curricula of host countries, it has developed an improved review system to remove bias in materials used in Palestinian schools.

In 2018, the Trump administration ended U.S. funding of UNRWA, expressing hope that the agency’s eventual elimination would change the longstanding international definition of Palestinian refugees and drastically reduce their numbers. The U.S. had been UNRWA’s top donor for decades, providing hundreds of millions of dollars annually. The administration’s decision was praised by many leaders in Israel, although Israeli defense officials have warned that UNRWA’s defunding could risk a humanitarian disaster in Gaza and allow Hamas to tighten its control of the territory. Additionally, responses from Palestinian leadership, along with opinion surveys of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza, indicate that the refugee issue will likely remain a critical element in the Palestinian narrative and in the diplomatic arena, with or without UNRWA.

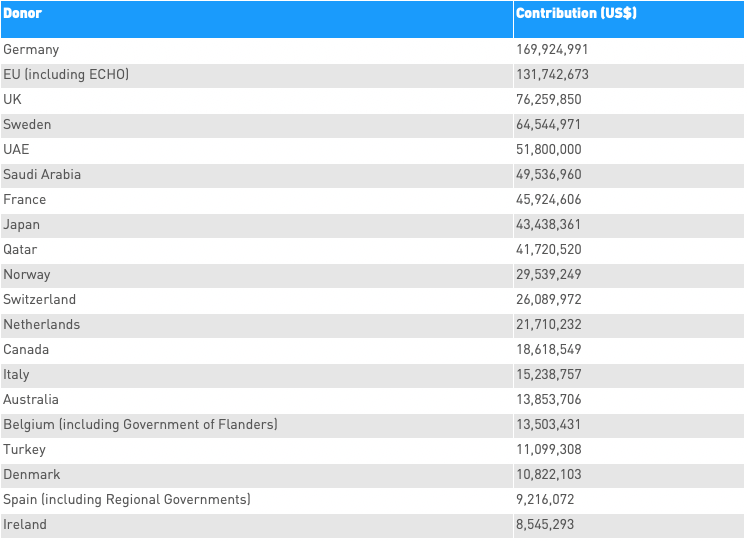

TOP 20 Government donors to UNRWA (2019)

IDENTITY ISSUES

The intangible, highly-sensitive questions of rights, dignity, responsibility and recognition are key to the refugee issue and central to how Israelis and Palestinians view themselves and the other. Both sides see these issues as zero-sum, and powerful social and psychological forces make flexibility difficult. Indeed, mistrust is so profound that even meaningful attempts at compromise will likely be perceived as insufficient, insincere — even insulting. Both sides fear that compromise on intangible issues could have severe implications for more concrete concerns.

Israeli and Palestinian flags (Shutterstock)

RIGHT OF RETURN

At the heart of Palestinian claims is the demand for Israeli recognition of a “right of return” for refugees and their descendants. They trace this right to an array of international legal instruments, primarily paragraph 11 of the 1948 United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194:

“Refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which, under principles of international law or in equity, should be made good by the Governments or authorities responsible.”

Palestinians approach the right of return as an individual right upheld collectively; it cannot be eliminated or withdrawn by states on behalf of their citizens. Palestinian leaders have, at times, showed flexibility on the right of return. But Palestinian willingness to express such ideas in confidential diplomatic channels has not been matched in public discourse. The refugee issue, together with Jerusalem are often understood to be “third-rails” in Palestinian internal politics.

The remains of a Palestinian home in Israel (Wikimedia Commons, 1948)

For their part, Israelis reject legal claims for return rights, and have a strikingly different interpretation of Resolution 194 — Israel has argued it is neither binding, nor at all clear how it would be implemented. Most Israelis consider any concession on a right of return to be an expression of weakness, even betrayal, seeing it as a threat to Israel’s Jewish majority and founding narrative. Many Israelis expect the Palestinians to forsake the right of return in an agreement, although negotiators largely understand such an explicit forfeiture to be highly unlikely.

Palestinian political poster (Shutterstock)

NARROWING THE CONFLICT

Israeli and Palestinian negotiators have explored compromises to resolve the refugee issue while protecting Israel’s Jewish majority. In an agreement, Israel could accept a Palestinian right of return in theory, combined with a Palestinian limit to the right in practice — satisfied primarily through Palestinian citizenship in a new Palestinian state. Consistent with this idea, former President Bill Clinton proposed language for return to “historic Palestine” or to the Palestinian “homeland.”

Israeli Prime Ministers Ehud Barak and Ehud Olmert are reported to have offered compromise formulas on the refugee question that would have allowed for limited numbers of Palestinians to “return” to Israel based on humanitarian grounds and family reunification (in the low thousands). Today, Palestinian leaders still publicly claim the “right” of return. However, in talks with Israel, negotiators have reportedly shown greater flexibility, simply demanding a “just” and “agreed-upon” solution. Mirroring the 2002 Arab Peace Initiative — backed by 57 Arab and Islamic countries — this language suggests that any resolution on refugees would need to be premised on Israeli consent.

Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas has himself suggested that he hopes to return to his childhood home in the Israeli city of Safed — but as a tourist, not to live there. Abbas’ statement was met with great resistance from Palestinians, and not convincing to Israelis.

Acknowledgment of Responsibility

Palestinians demand an Israeli acceptance of its practical and moral responsibility for creating the refugee problem, including acknowledgment of and apology for 1948 events. Israelis categorically reject that reading of history. Furthermore, any recognition of responsibility threatens to undermine the Israeli narrative by implying that Israel was founded “in sin,” and could also carry legal obligations to rectify the situation. These perspectives directly contradict each other, and thus far, creative formulas have failed to bridge the gap.

Oval Office meeting with President Obama and Vice President Biden with Israeli and Palestinian negotiators (Chuck Kennedy, 2013)

In past negotiations, Israel has expressed willingness to acknowledge the suffering of Palestinian refugees, but not an Israeli role in that suffering. Israeli leaders have, however, agreed to contribute to an international fund for Palestinian refugees that could symbolically address, and perhaps substitute for, a recognition of responsibility. Polling suggests that Israelis might be willing to admit partial responsibility for the refugee situation, if Palestinians acknowledged their own role in rejecting the Partition Plan, or in fueling Palestinian terrorism. For their part, Palestinians have refused, as they see it, to find themselves responsible for their own tragedy. Another possible compromise could have Israel only acknowledge its role in prohibiting Palestinian refugees from returning after the war, as this is not in dispute. Ultimately, “constructive ambiguity” could allow both sides to accept language as consistent with their national narratives, without alienating the other side.

Options for Resolving Identity Issues

Some argue that questions of historical narrative simply have no place in final-status negotiations. Likewise, Israeli and Palestinian leaders have largely deferred identity issues in negotiations in order to address more practical concerns. There is little political will to address issues of rights and responsibility, and the parties may have better success in resolving them in a post-conflict environment. On the other hand, resolving the issues now could build trust for tackling other issues, while deferring identity issues could weaken an agreement in the long- term and allow hatred of the other side to fester. Ultimately, to achieve an agreement, compromises will have to be made by both sides. But Israelis and Palestinians have expressed that an effective response to identity issues could allow more flexibility on the practical issues of the conflict.

Palestinian woman holding up key to family home (Shutterstock)

Residency and Citizenship

Any resolution of the refugee issue will likely provide a pathway to permanent residence or citizenship, thus ending the refugees’ stateless status. Giving refugees a sense of choice in determining their place of residence would also be important to a population that perceives itself as having been denied such agency for decades.

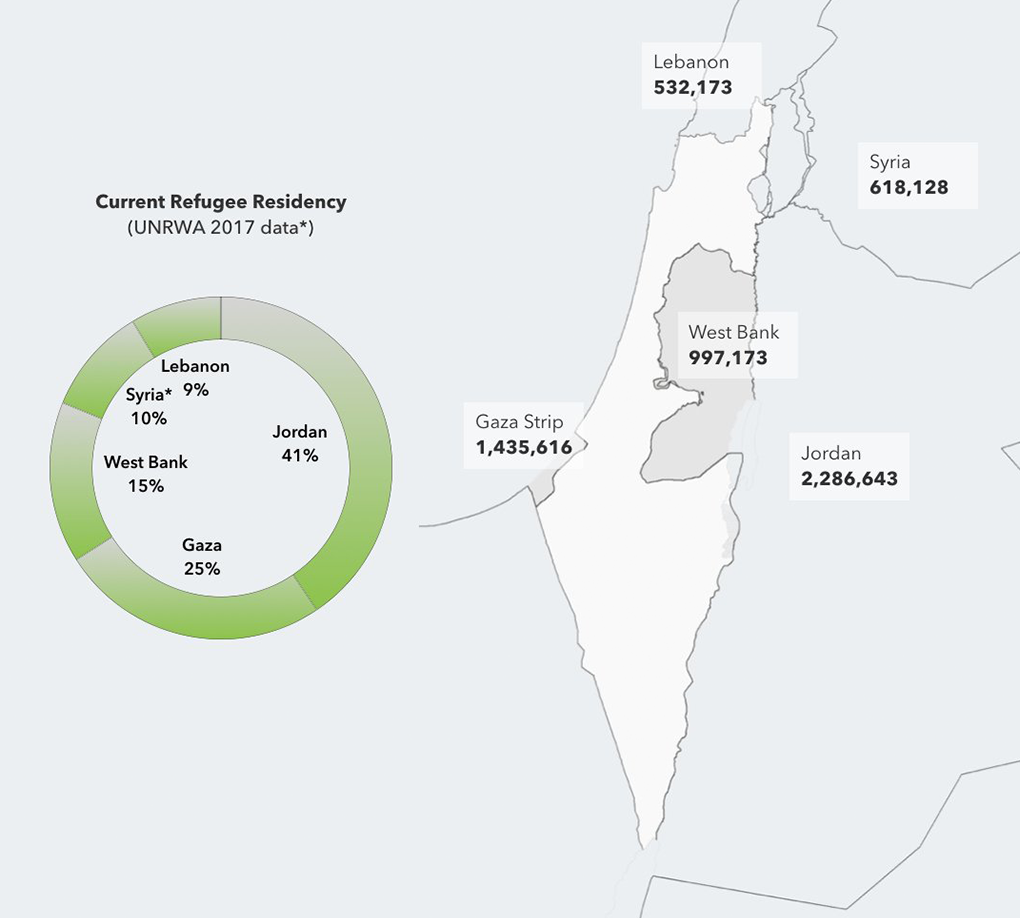

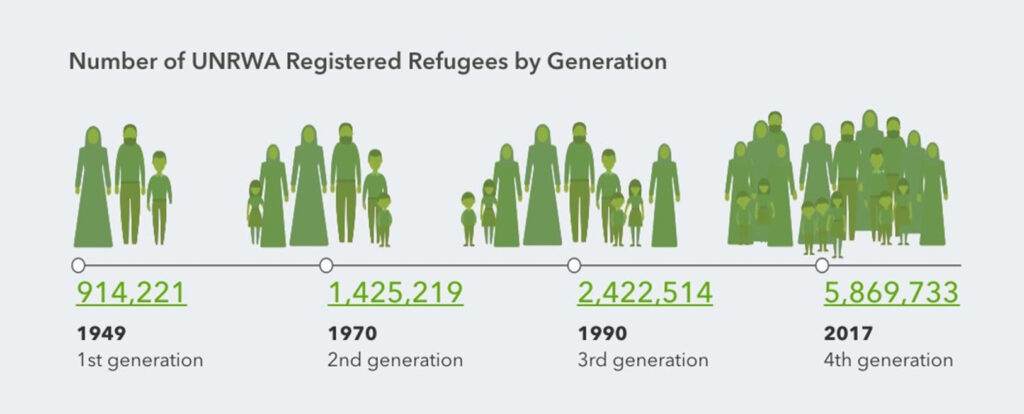

Number of registered persons according to UNRWA

Repatriation

One option would be to repatriate refugees to exercise self-determination in the new Palestinian state. Of symbolic significance to some refugees could be the possibility of repatriating to territory that had been part of Israel-proper, but would be traded to the new Palestinian state in a land-swap, as part of a final-status agreement. Although all Palestinians, in theory, could have the right to citizenship in the Palestinian state, there is a risk that rapid immigration to the new state could pose great strain on its economy and viability.

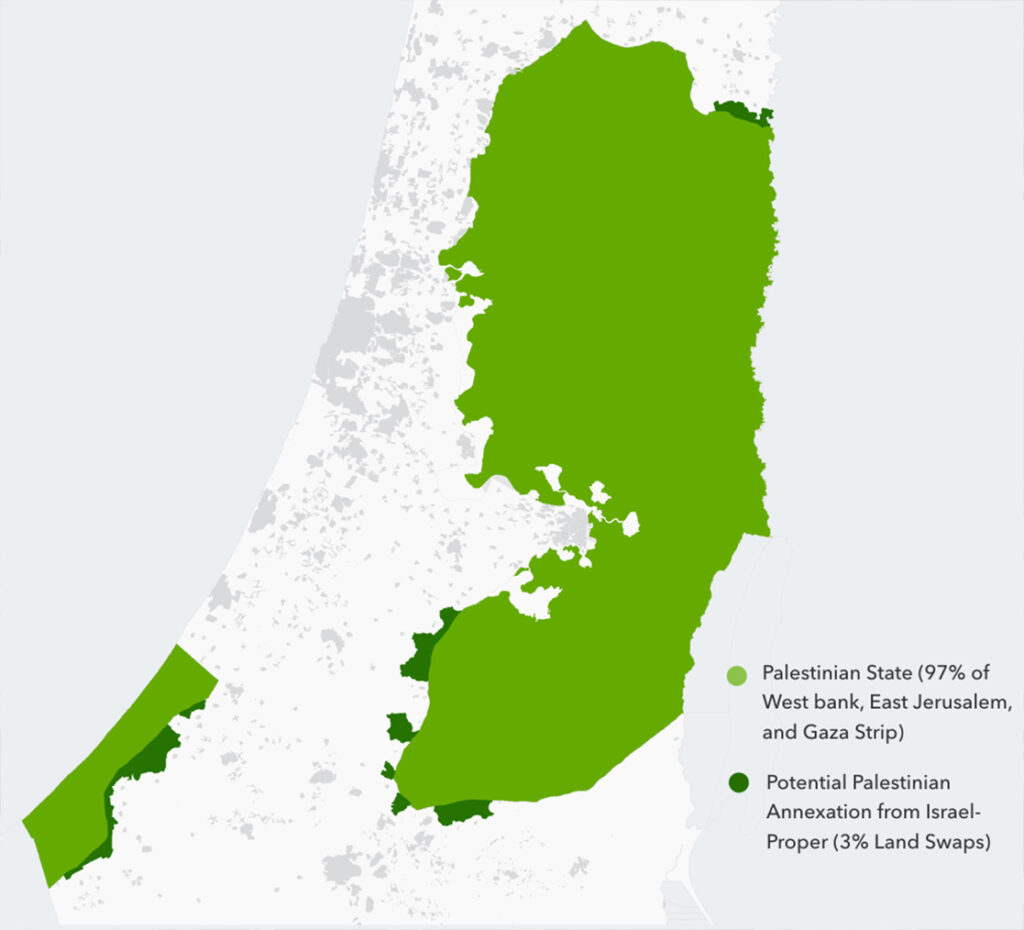

Illustration of borders with 3% land swaps

Return

In past negotiations, Israeli and Palestinian representatives debated a limited return of Palestinian refugees into Israel. This issue is most contentious due to the Israeli concern that Palestinian immigration could upend Israel’s demographic balance and threaten its future as a Jewish state. Therefore, Israel has demanded an upper limit, to heavily constrain the magnitude of refugee return and avoid any long-term or open-ended commitment. However, for the Palestinians, any number, especially if it is too low, might conflict with the principle of giving Palestinians a choice in exercising the right of return. In practice, Israeli negotiators have hardened their positions over time, from agreeing to absorb 40,000 refugees in 2001, to lower numbers in 2008, and ultimately, rejecting any absorption today. Palestinian positions have also varied over the rounds of negotiation, between 80,000 and 300,000.

Other options raised over the years include setting an annual rate of refugee return for an indefinite period (which was rejected by Israel), or a link between the number of refugees to Israel and the number of refugees resettled in third countries. Still, others have proposed linking the number of refugees absorbed by Israel to the number of Israeli settlers who could be permitted to remain in the new Palestinian state. Some suggest that there is currently a narrow window of opportunity for compromise — so long as a few thousand original Palestinian refugees still live.

An Israeli recognition of the right of return for first-generation refugees born before 1948 could provide a meaningful resolution of the refugee issue — indeed, an unprecedented breakthrough — without jeopardizing Israel’s Jewish majority. Lastly, there is disagreement over how to characterize refugee absorption to Israel — Palestinians demand the symbolic terminology of ‘return,’ while Israel insists on language of ‘humanitarian gestures’ and ‘family reunification.’ Negotiators have explored how ambiguity in agreement language could help bridge differences, though it could prove counterproductive once the agreement were subject to public debate.

Number of UNRWA registered persons by generation

Integration

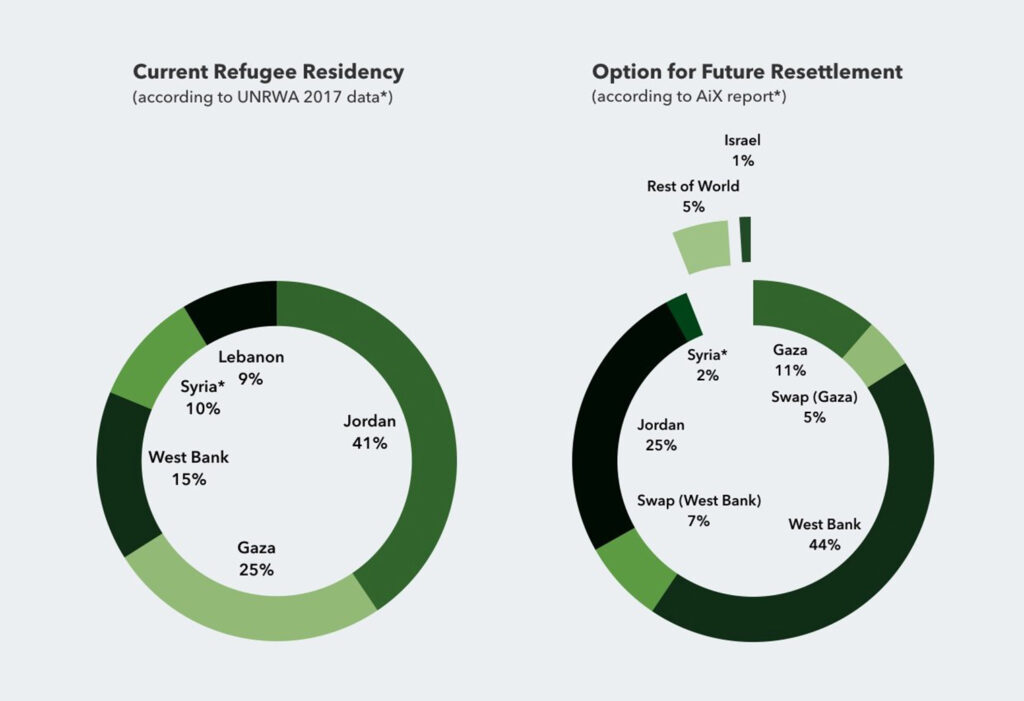

A solution to the Palestinian refugee issue would likely offer integration for refugees living in third countries who choose to remain, contingent on approval from their host countries. As many refugees currently live in refugee camps, significant funding would likely be needed to integrate them as permanent residents, especially in terms of housing, employment, infrastructure, education, and health. Such a plan could be part of a broader economic development initiative in the region. Notably, Lebanon and Syria, which have hosted nearly 20 percent of Palestinian refugees over time, have strongly opposed permanent integration of their refugee populations. Jordan, home to the largest Palestinian community outside the territories, presents a different model given the extent to which most have already integrated.

Resettlement

Another important component would be resettlement in countries that would be willing to take in refugees as permanent residents or citizens.

Future resettlement based on analysis by the Aix Group

Compensation

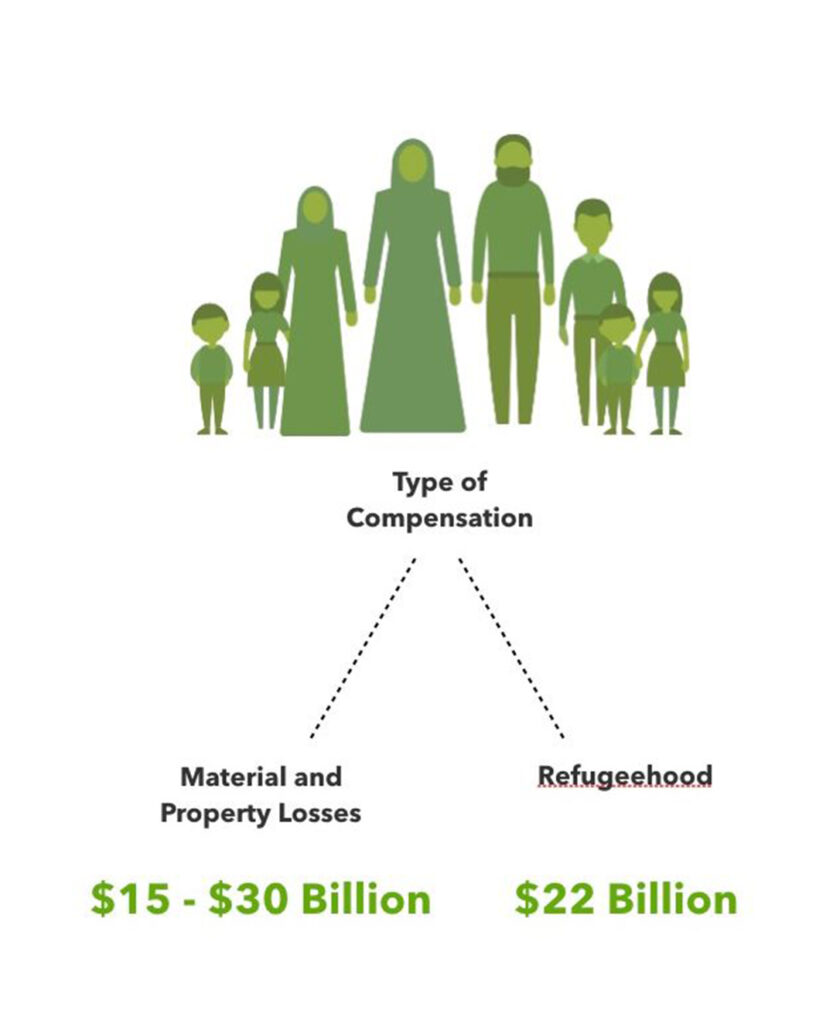

Figures based on Aix Group report summary: Economic Dimensions of a Two- State agreement between Israel and Palestine (Vol II: Supplementary Papers, 2010)

Compensation is a central part of a comprehensive solution to the Palestinian refugee issue. Previous negotiations focused on two types of compensation: Compensation for refugeehood or suffering — sometimes referred to as ‘fast track’ — is essentially per capita compensation that all eligible (however the parties agree to define them) refugees would be entitled to. Compensation for material and property loss — sometimes called slow, or evidential, track — aims to compensate refugees for specific assets left behind, and presents a unique challenge in terms of providing evidence for assets that date back decades and even centuries.

Drawing on international law and the 1948 United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194, the Palestinians have pushed for open-ended compensation for all Palestinian refugees, stressing that Israel itself must take responsibility for funding. Israeli negotiators have demanded that the international community play the primary role in funding compensation, and only in a one-time lump sum to Palestinians who previously owned land within Israel. Although the parties agree in principle on compensation for assets and suffering, there is considerable disagreement over how refugees should prove past ownership of assets, and how the value of those assets should be calculated.

Some proposals advocate that an agreement also include funds to repay the countries who have hosted the refugees for decades. Although the need for such compensation is debatable, it would certainly incentivize these countries to support the peace deal, and perhaps encourage them to allow refugees to remain in their countries as permanent residents.

One word of caution: There is a big question mark regarding the viability and wisdom of varying compensation schemes. In all likelihood, the amount of funding that would be available for compensation would be significantly less than what refugees expect, raising the risks of a backlash among disillusioned or disappointed refugees. Estimates for required funding for refugee compensation have differed greatly — from as little as $3 billion and as high as $200 billion. The AIX Group, comprised of Israeli and Palestinian economists and scholars, estimate that the total amount would be $55-85 billion.

Oversight and Implementation

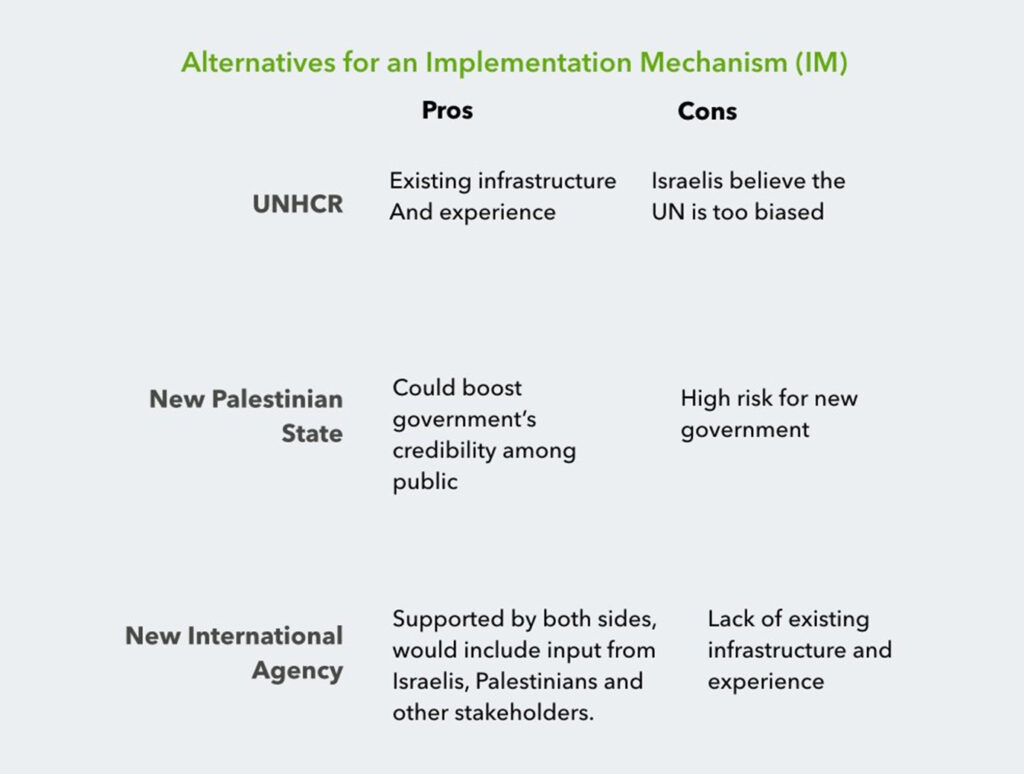

An elaborate plan that deals with refugee residency options and compensation would require a complex implementation mechanism (IM). One option would be to build the IM out of an existing body to minimize the need for negotiating an entirely new bureaucracy. The office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, which actively deals with such issues, might seem like a natural choice. However, given the politics surrounding the U.N. and Israel, Israelis have largely dismissed this option. Another option could be to use the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee within the World Bank, a longstanding donor structure that has worked to fund the PA and international NGOs for Israelis and Palestinians.

Alternatively, the IM could be run by a new agency within the PLO or as part of the new Palestinian government, potentially boosting the Palestinian leadership’s credibility, which could be helpful in light of compromises it would likely have to make on other issues. Still, Palestinians might hesitate to take on such a complex process that will inevitably be the subject of criticism and complaints.

Lastly, there is the possibility of a newly-established international agency, composed of representatives of the two parties, regional stakeholders, and international members. Both Israelis and Palestinians have favored this idea in past negotiations, including an independent international commission, and an international fund, with significant participation from the World Bank. Still, the parties have differed over the level of detail to be included in an agreement, with Palestinians supporting a higher level of detail, and Israel supporting most details to be worked out later with the IM.

The effectiveness of the IM would depend on the level of engagement with Israel, the new Palestinian state, the U.S. and the international community. With expectations high, there will be intense pressure on the IM to deliver rapid results.

Pro/Con chart of alternatives for an implementation mechanism

Digging Deeper

“Position on Refugees” Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) – Negotiations Affairs Department

”The Privileged Palestinian “Refugees” The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies – Efraim Karsh

“The Palestinian Refugee Problem” Rex Brynen and Roula El-Rifai

“Bringing Back the Palestinian Refugee Question” International Crisis Group

“The Palestinian Refugee Issue: Normative Dimensions” Chatham House

“Resolution to the Palestinian Refugees within a Two-State Agreement” AIX Group

“Solution to the Problem of the 1948 Palestinian Refugees” Geneva Initiative

*These materials are provided for reference purposes, with no intention of endorsement.