Jerusalem

Perhaps the most complex of all issues that divide Israelis and Palestinians, the question of Jerusalem is central to both sides’ narratives, internal politics and diasporas. Moreover, Jerusalem also involves a wide array of outside parties that have stakes in the city’s future, particularly in terms of property and religious sites and institutions, including Jordan, the Vatican, Islamic communities and various national and international churches. Seemingly intractable, given periodic tensions and the zero-sum rhetoric that often characterizes debates, behind the scenes there has been important progress toward finding acceptable solutions.

October 7th Update

Hamas named the October 7th attack the “Al-Aqsa Flood” hoping to link its attack to the idea of freeing Jerusalem from Jewish control. While other parts of the region have been enflamed through the war in Gaza, Jerusalem for the most part has remained relatively calm without increased tensions on the Temple Mount. This relative calm may be challenged during Ramadan in March 2024 and other periods of heightened sensitivity should the war still be going on. So far, though, Hamas has not managed to get East Jerusalem residents to join in the fight.

Background

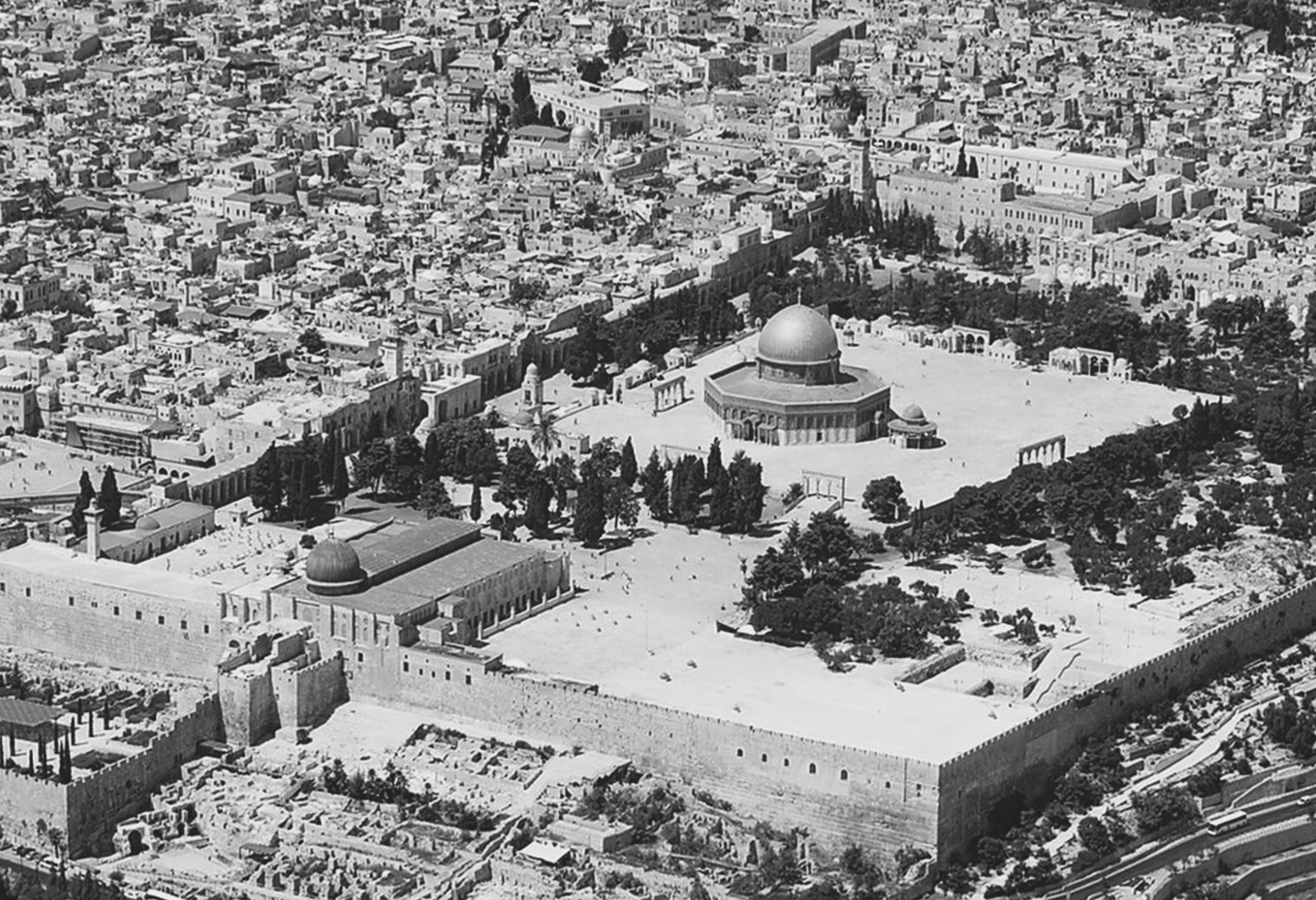

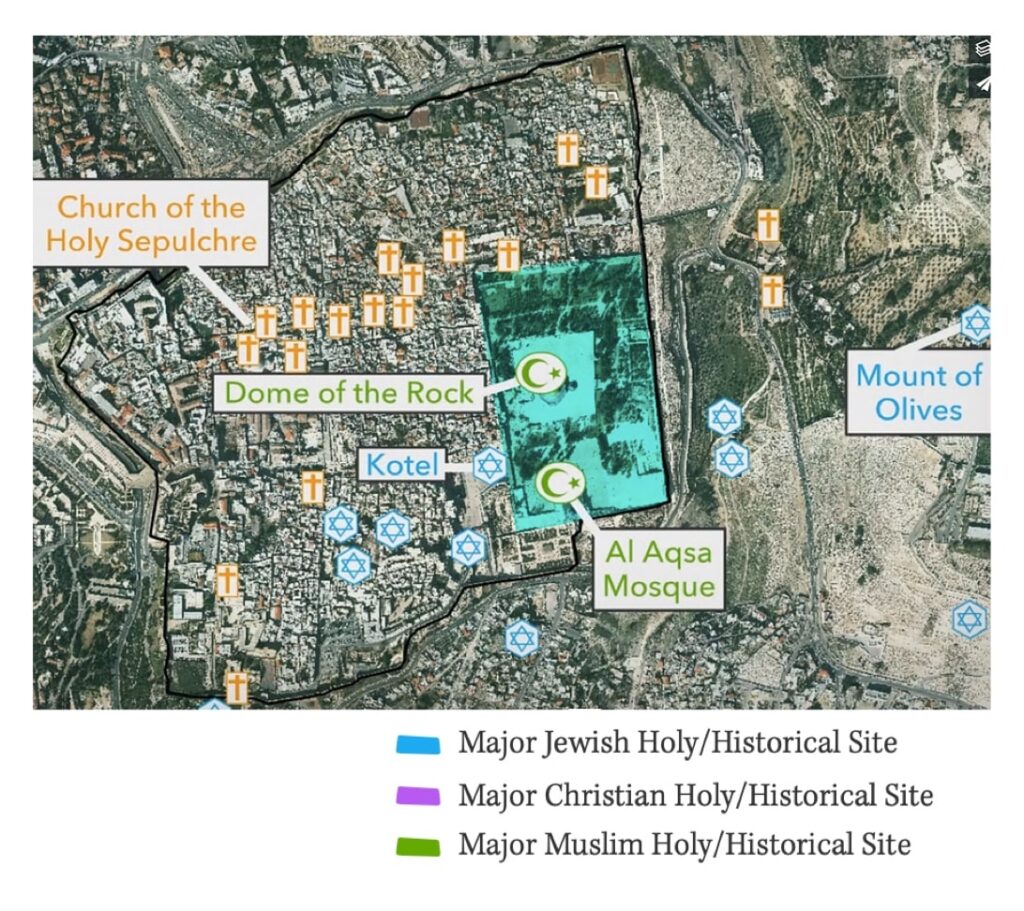

The historical and religious significance of Jerusalem is deeply embedded in the narratives of both Israelis and Palestinians and resonates far beyond the Middle East. Jerusalem was the site of the first and second Jewish Temples; it was the capital of the ancient Israelite kingdom and Jews have maintained a presence in the city for millennia. The city is also where Muslim tradition holds that the Prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven. Likewise, it is where Christians believe Jesus was crucified, buried, and resurrected. The Old City of Jerusalem is home to sites of enormous religious importance, including the Temple Mount/Haram Al Sharif, Western Wall, Church of the Holy Sepulcher, Dome of the Rock, and al-Aqsa Mosque.

Although the 1947 UN Partition Plan would have placed Jerusalem under international control — neither Israeli nor Arab — the 1948-49 war left the city deeply scarred and physically divided: Israel controlled the west, and Jordan controlled the east — including the entire Old City. As a result of the 1967 War, control of the entire city passed to Israel. Soon after, Israel annexed East Jerusalem and additional surrounding Palestinian villages into a vastly enlarged and physically undivided Jerusalem municipality. Israel’s annexation has not been recognized by the international community, though the United States recognized the city as Israel’s capital in 2017. Even though the U.S. moved its embassy to Jerusalem the following year, President Trump explicitly stated that Jerusalem’s final borders would still be subject to final status negotiations. These policies have been maintained by the Biden administration.

Jerusalem is also a teeming, multi-ethnic, modern city of nearly a million residents, developing rapidly despite its turbulent modern history.

The Light Rail in Jerusalem (Shutterstock)

About 60 percent of the city’s population is Jewish, and about 40 percent is Arab Palestinian (Arabs are a majority in the densely populated Old City). Although physically undivided, the city’s Jewish and Arab populations and neighborhoods maintain a largely separate existence.

There are ongoing attempts to increase the Jewish presence in Arab neighborhoods using a mixture of property purchases, legal appeals, and evictions. The neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah has recently been the focus of protests and international attention ultimately sparking an eleven-day clash between Israel and Hamas in Gaza.

Jerusalem Skyline

QUESTION

Can Jerusalem serve as the capital of both Israel and a future state of Palestine and can a formula be found that addresses both sides’ claims to historical and religious sites?

ISRAELI PERSPECTIVE

The Israeli government considers the city “Israel’s eternal and undivided capital” — highlighting the Jewish people’s historic connection to Jerusalem, and the “unification” of the city in 1967 after 19 years of Jordanian control of the eastern part. Israel has pledged to ensure access for all faiths to the Old City’s religious sites, and many Israelis are convinced that only Israel can be trusted to do so, citing its record over the past 50+ years. Some Israelis also push for greater Israeli control over the Temple Mount, which remains largely under the administration of the Islamic Waqf, or religious authorities. This push has been pronounced in recent years under the current Israeli coalition government. Several notable examples of flare-ups around the Temple Mount include an Israeli police raid of the al-Aqsa/Temple Mount compound in April 2023, Minister of National Security Itamar Ben-Gvir’s (Otzma Yehudit) multiple visits to the Temple Mount in the same year as well as his calling to ban certain Palestinian worshippers during Ramadan in 2024. However, the longstanding Israeli position in support of the “status quo” enjoys broad public support.

The Kotel (Western Wall) with Israeli Flag (Shutterstock)

In 1980, the Israeli Knesset passed a law that sought to deepen the state’s jurisdiction over the enlarged municipality of Jerusalem. Many Israelis believe Israel should be able to build in its capital without restrictions, and they do not consider the sprawling Jewish areas built post-1967 to be “settlements.”

The Jewish diaspora, including American Jewry, is deeply attached to Jerusalem, as evidenced by extensive social, educational, and philanthropic ties. Jews worldwide consider Jerusalem to be Israel’s capital, which is why President Trump’s recognition and Embassy move enjoyed consensus support. President Biden’s decision to maintain the Trump administration’s policy reaffirmed this broad support. That said, diaspora views are more divided when it comes to recognizing Palestinian claims and potentially a future Palestinian capital in East Jerusalem, should the parties agree to one as part of a peace deal.

There is a presumption within Israeli politics that any agreement that would limit Israeli control over the entirety of Jerusalem, including the Old City, would be unacceptable. Still, the receptivity for various compromise formulas has never been fully tested, partly because the question is so sensitive politically that the Israeli leaders who have negotiated over Jerusalem’s status have done so quietly, often secretly, without engaging the Israeli public. Despite this taboo, there are indications that Israelis would support solutions that relieve Israel from having to fully absorb the city’s large Palestinian population, which some view as a demographic threat.

In terms of the city’s holy places, Israel has repeatedly acknowledged the interests and role of other parties, as reflected in the 1994 Israel-Jordan peace treaty and the 1993 Israel-Vatican agreement.

PALESTINIAN PERSPECTIVE

Palestinians assert a historical, religious, social and cultural claim to Jerusalem, and demand that “East Jerusalem” be the capital of a future Palestinian state. Jerusalem has long played a central role in Palestinian politics and social affairs, even during the 50+ years of Israeli control. Important Palestinian institutions are located throughout East Jerusalem, including hospitals, universities, and many cultural sites. Palestinians—and most of the international community—reject the legality of Israel’s annexation of East Jerusalem, and oppose the expansion of Jewish development into Palestinian neighborhoods. They also object to the wide disparities in social services and public infrastructure for East Jerusalem Palestinians—roughly 40 percent of the city’s population. Many Palestinians are particularly sensitive to the status quo of the holy sites, controlled by Israel with Jordanian religious oversight, and have accused Israel repeatedly of violating the status quo. Palestinians also object to Israel’s recurrent closure of their institutions in the city.

Al-Aqsa Mosque (Shutterstock)

The official Palestinian position, as articulated by the PLO, proposes that “Jerusalem will remain an open city, with freedom of worship guaranteed to believers of the three monotheist religions in their holy shrines.” “West Jerusalem,” they assert, “will be the capital of the State of Israel and East Jerusalem will be the capital of the State of Palestine.” Beyond these general principles, a more nuanced, detailed official Palestinian position is more difficult to ascertain, as Palestinian leaders have been more reticent than some Israeli leaders about putting forward detailed proposals on Jerusalem.1 “Palestinian Position on Core Issues,” PLO paper, April 2019.

The Palestinian diaspora also maintains deep attachments to Jerusalem, generally supporting the political positions of local Palestinian leaders. Across the broader Arab and Islamic worlds, concerns about Jerusalem focus less on the modern city and its political status and more on the narrower issue of control over holy sites.

To sum up the Palestinian position, Palestinians demand a capital of their own in East Jerusalem based on the 1967 lines, including sovereignty over most of the Old City. That said, similar to the dynamic in Israel, Jerusalem is a highly explosive subject in Palestinian politics and Palestinian leaders who have negotiated over its status have done so quietly, often in secret and Palestinian public willingness to accept compromise formulas is yet to be fully tested.

RECOGNITION AS ISRAEL’S CAPITAL

When the United Nations Partition Plan divided Mandatory Palestine into a Jewish state and an Arab state, it granted the greater Jerusalem area a separate status, to be administered by the UN itself. Due to Arab rejection and the ensuing war, that plan was never implemented.

Today, Jerusalem serves as Israel’s capital in practice, with the Prime Minister’s Residence, Knesset, Supreme Court and most government offices located there. At the same time, most of the international community maintains that all the areas east of the 1967 lines are ”occupied territory”. Furthermore, in deference to the city’s still unresolved status, the vast majority of countries have long refrained from operating embassies in the city.

U.S. Embassy in Jerusalem (Shutterstock)

As agreed in the 1993 Oslo Accords, Israel and the Palestinians pledged to negotiate the status of the city. This negotiation was to take place as part of “final-status” negotiations that were never completed.

This approach was backed by numerous American administrations despite some pressure from Congress. Specifically, Congress passed the Jerusalem Embassy Act in 1995 which called on the United States to recognize Jerusalem as “the capital of the State of Israel” and move the American Embassy to the city from Tel Aviv. However, from 1995 until 2018, every US president had signed a waiver delaying the embassy move by six months.

Under the Trump administration, the United States shifted its policy, recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and moving its embassy there. Supporters of this move argue that the recognition simply acknowledged reality — Jerusalem already operates as Israel’s capital — and the Trump administration stated that it had not taken a position on final-status issues. Opponents contend that the move pre-determined the status of Jerusalem and criticize the failure to recognize Palestinian aspirations for a capital in East Jerusalem. However, the Trump administration acknowledged that the boundaries of Israeli sovereignty of Jerusalem would still be determined in “final-status” negotiations.

Moreover, as part of the move, the Consulate-General in Jerusalem, which had served as an independent channel from Washington to Palestinians, was merged with the U.S. embassy. This meant relations with Palestinians would be conducted through the Palestinian Affairs Unit and subject to oversight by the US Ambassador to Israel. Though Joe Biden promised to re-open the US Consulate during his election campaign in 2020, he has yet to do so. Still, in 2022, the Biden administration renamed the Palestinian Affairs Unit as the Office of Palestinian Affairs and indicated that it would report not to the US ambassador, but to the Near East Affairs Bureau at the State Department. The US embassy remains in Jerusalem and the Biden administration has stated that it will remain there.

HELPFUL REALITIES

A Solution for municipal Jerusalem:

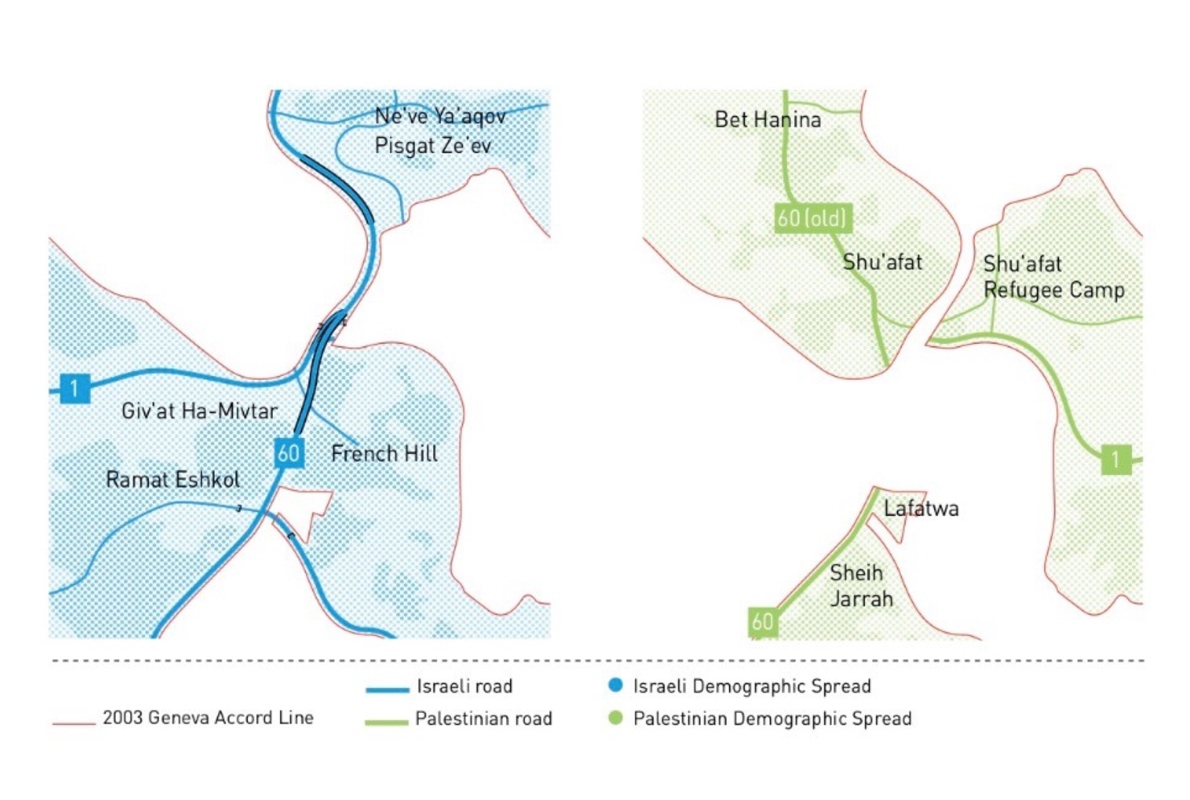

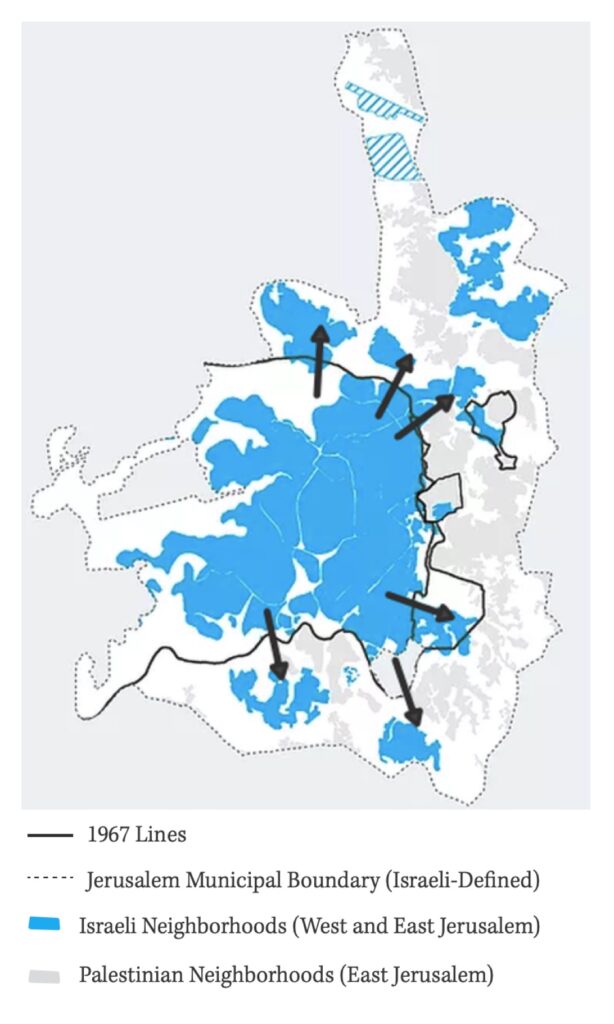

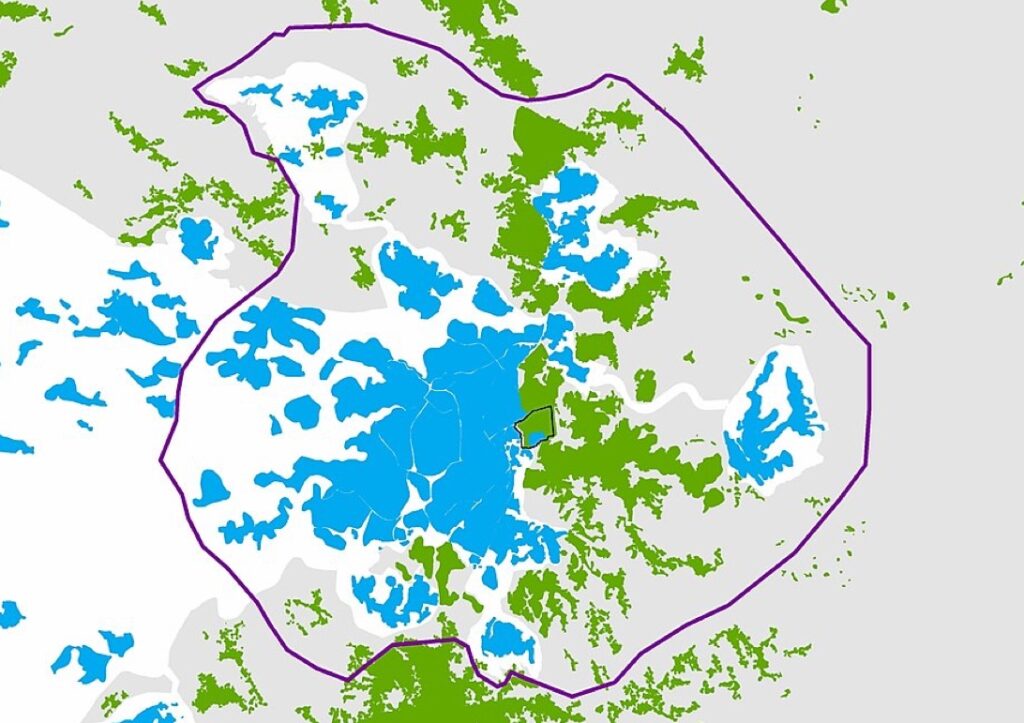

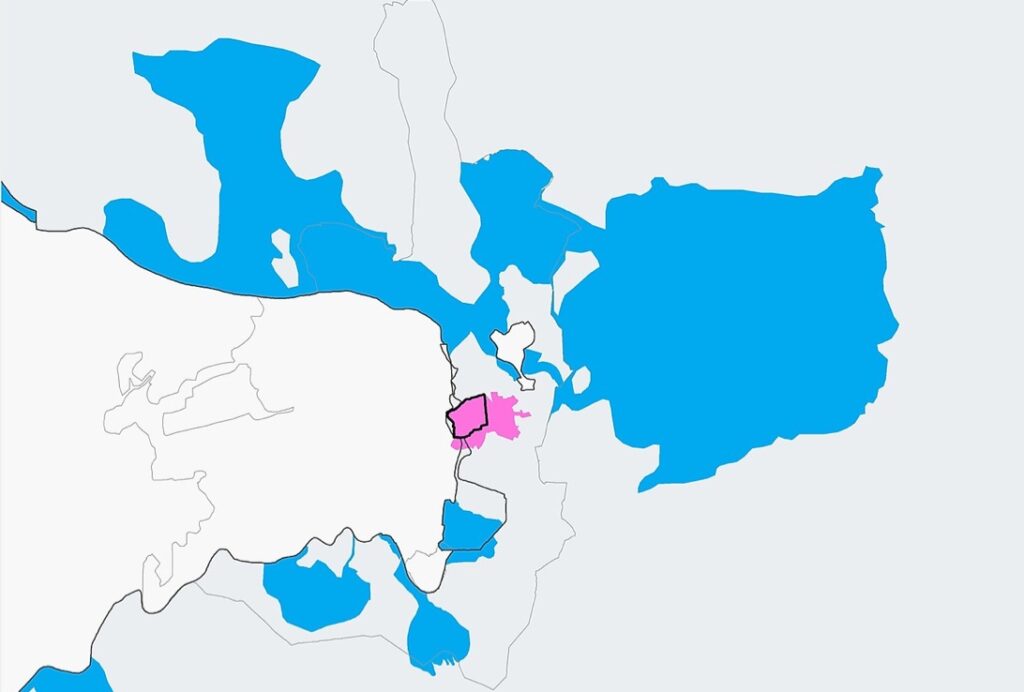

When determining a solution for municipal Jerusalem, Israelis and Palestinians are only negotiating over East Jerusalem. One factor that makes drawing a border possible is that the vast majority of the city’s Jews live in largely Jewish neighborhoods in the “western” areas of the city, and the vast majority of the city’s Palestinians live in largely Palestinian neighborhoods in East Jerusalem. The largest Jewish neighborhoods in East Jerusalem are also contiguous with West Jerusalem—potentially allowing for the creation of two separate and internally contiguous capitals for each country. And although Jerusalem has technically been unified since 1967, there is still little interaction and few shared public institutions between the two communities. Splitting the neighborhoods along Israeli and Palestinian lines would not dramatically alter the daily routine of the vast majority of residents.

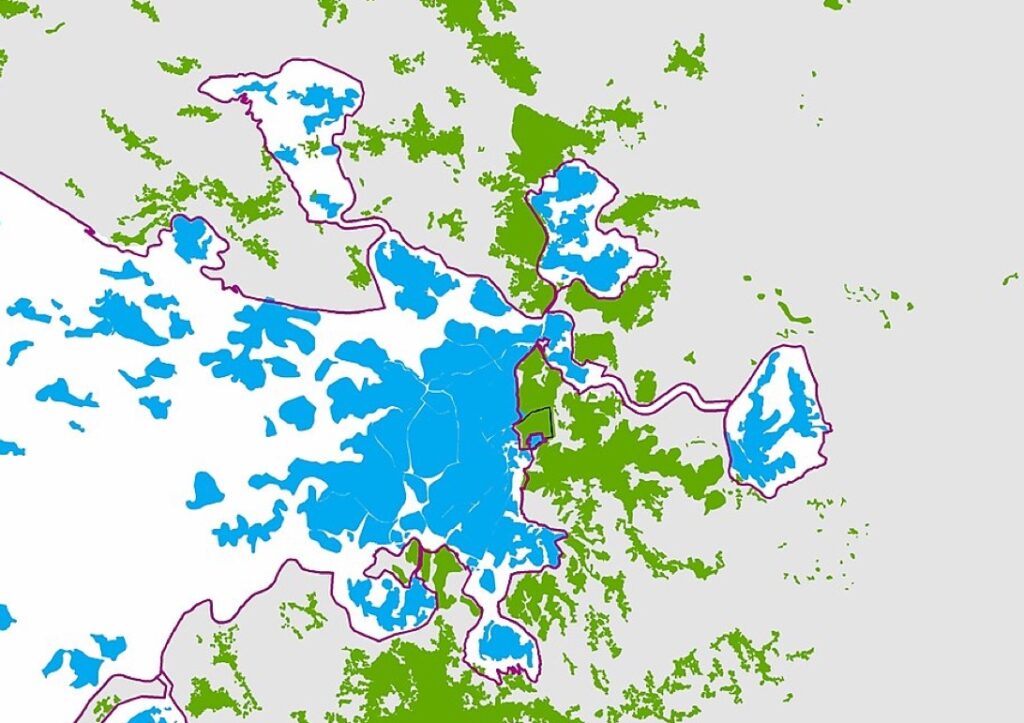

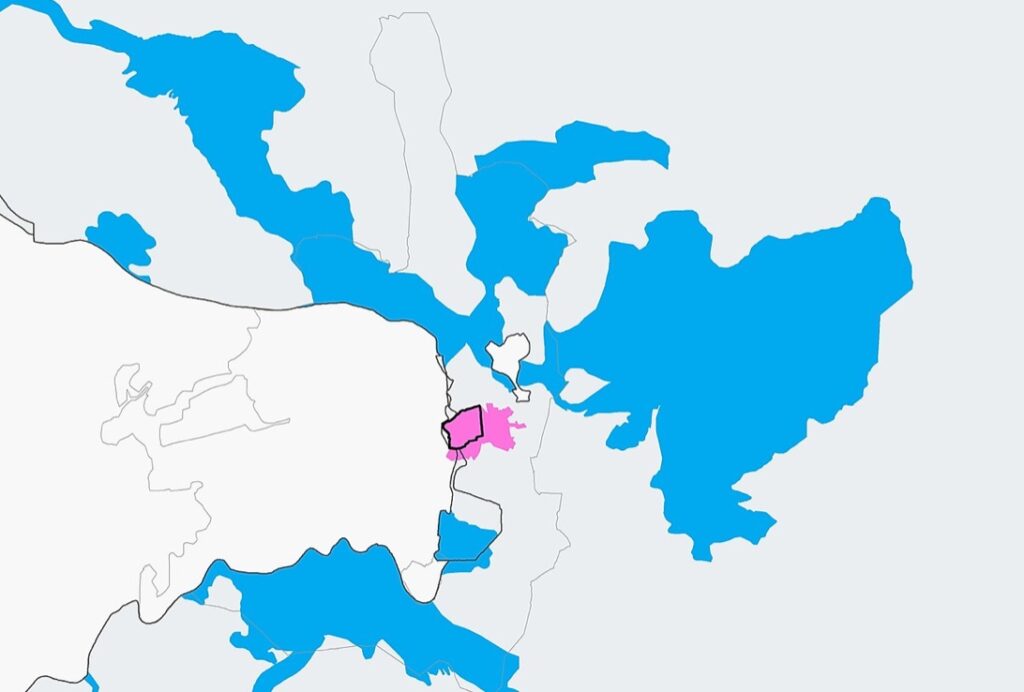

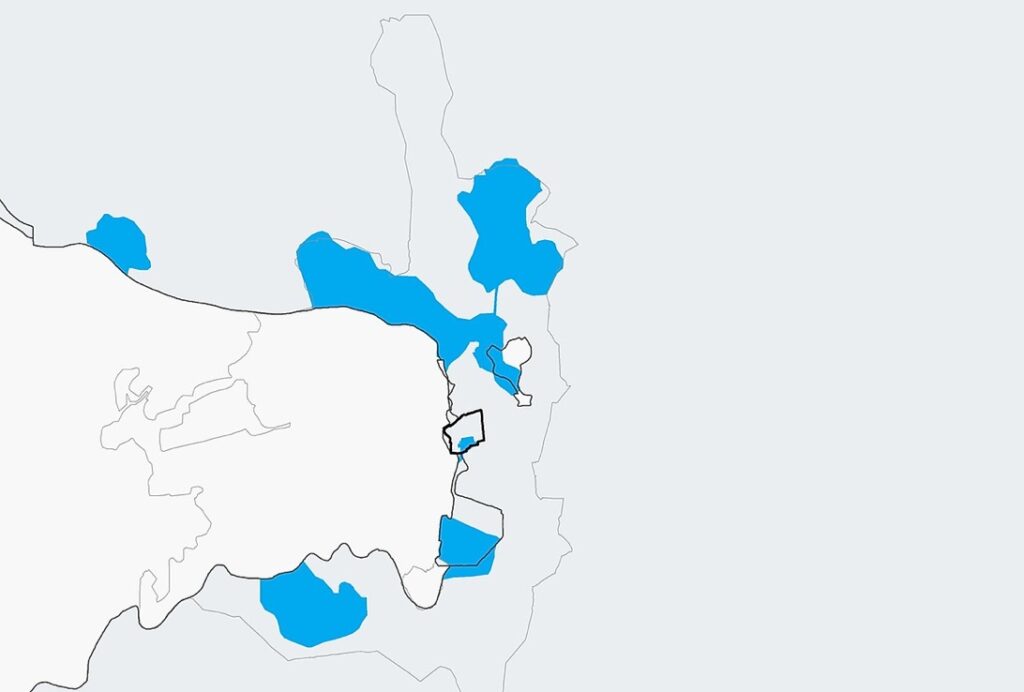

Jerusalem municipal boundaries

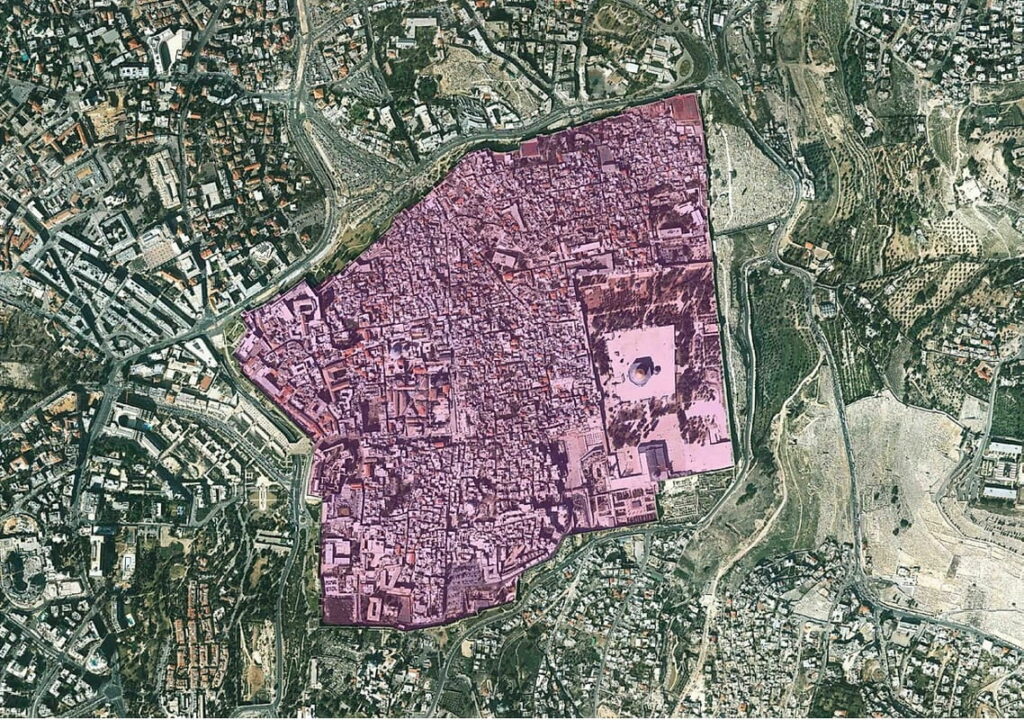

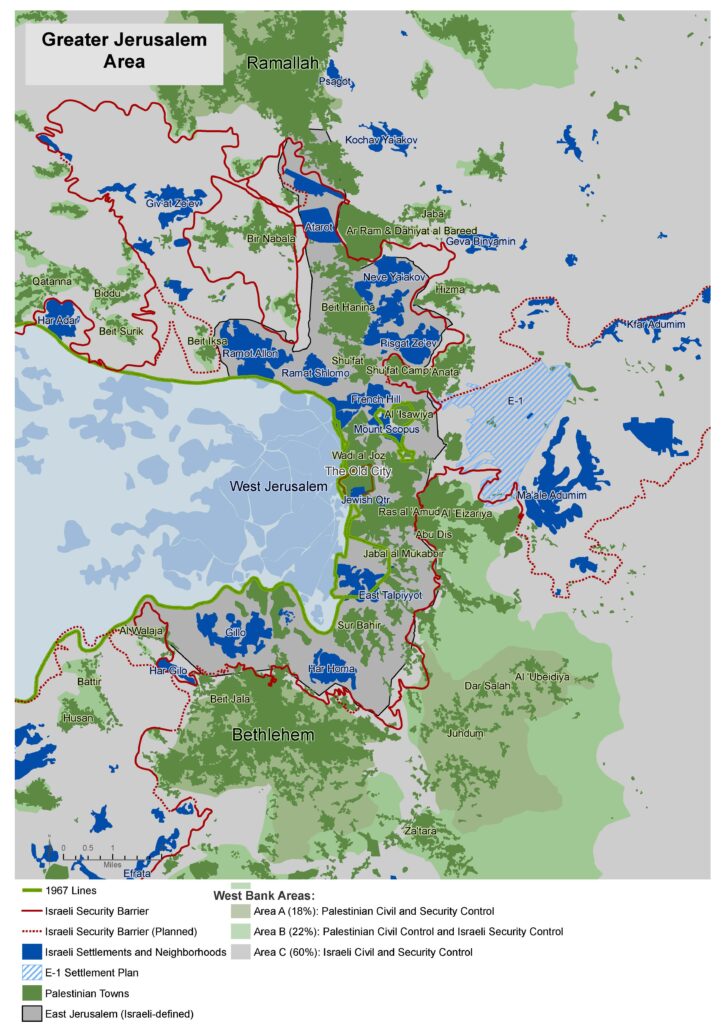

It is helpful to distinguish between the historical city of Jerusalem—which carries the bulk of the historical and religious significance for both sides—from the modern day city of municipal Jerusalem, whose boundaries were delineated by Israel after the 1967 War. The historical city — the Jerusalem of the Hebrew Scriptures, New Testament, and Koran, and even as recently as the early 20th century — represents just a tiny sliver of the city that today bears the same name. Most of the land with religious and historical significance is located in the Old City and the area around it known as the Holy or Historic Basin.

Because municipal Jerusalem is largely devoid of contentious sites, the challenge is to create two viable and contiguous capitals whose geography has become both intertwined, as well as remaining separate, over the past 50+ years.

Greater Jerusalem Area

NARROWING THE CONFLICT

One possible solution, outlined by President Bill Clinton in 2000, proposed that the capital of the state of Israel consist of the city’s Jewish areas creating Yerushalayim, the Hebrew word for Jerusalem — and the capital of the future Palestinian state consist of the Palestinian areas—Al-Quds, the Arabic name for Jerusalem.

Despite the relative separation of Jerusalem’s Jewish and Palestinian populations, the city is one urban unit, which presents a challenge for drawing a traditional border straight through it.

In later negotiations, including during what was known as the Annapolis process (2007-2008), additional compromise formulas were suggested by the Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert.

An Open City

One option is to maintain Jerusalem as an “open city,” with unimpeded movement between its Israeli and Palestinian parts. This model would avoid the need to erect physical barriers and border crossings in the densely populated urban areas — constructing a border outside the city instead. But the “open city” model creates numerous challenges, including the need for a security envelope around Jerusalem; maximal cooperation between the two countries inside the city; and a special economic regime within the city.

Residential areas in an united city of Jerusalem

A Divided City

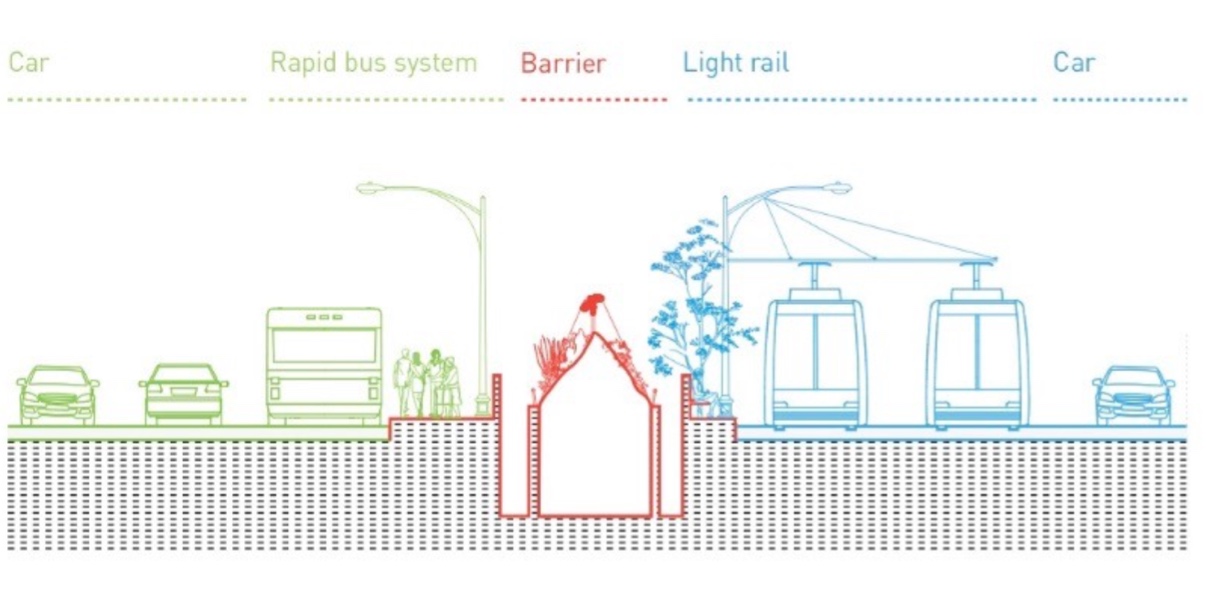

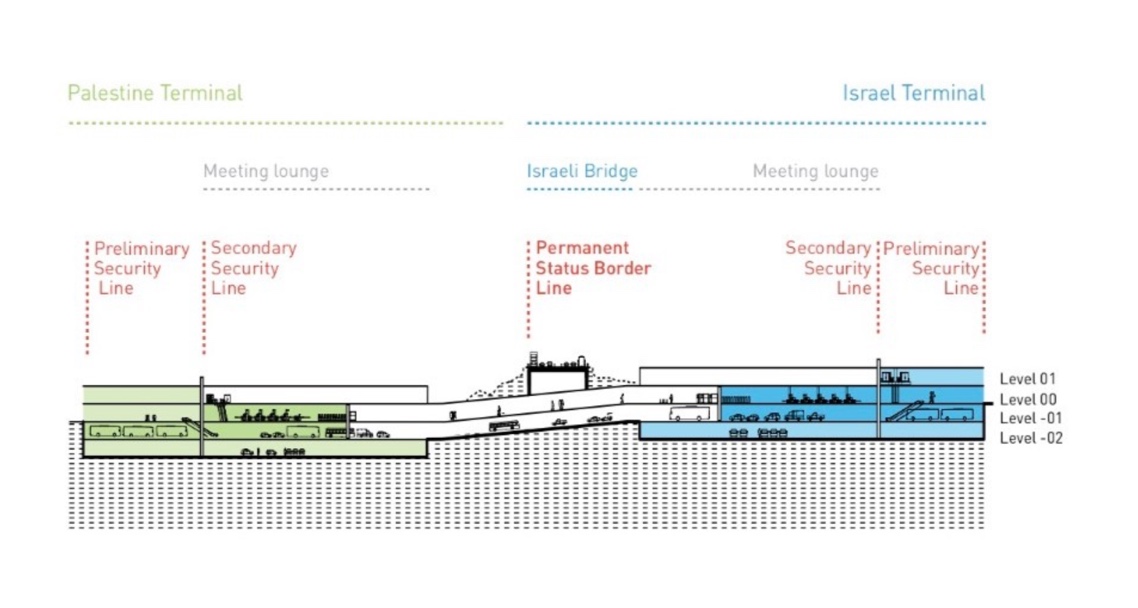

Another potential solution for municipal Jerusalem would be a divided city, which may bring to mind Berlin during the Cold War, Nicosia in Cyprus, or even Jerusalem between 1948-1967. To avoid these scenarios, the border would need to provide adequate security while preserving both cities’ urban fabric and quality of life, and also facilitating the movement of people and goods across the border. In other words, an effective border would have to simultaneously separate and connect the two cities.

Residential Areas in a divided city of Jerusalem

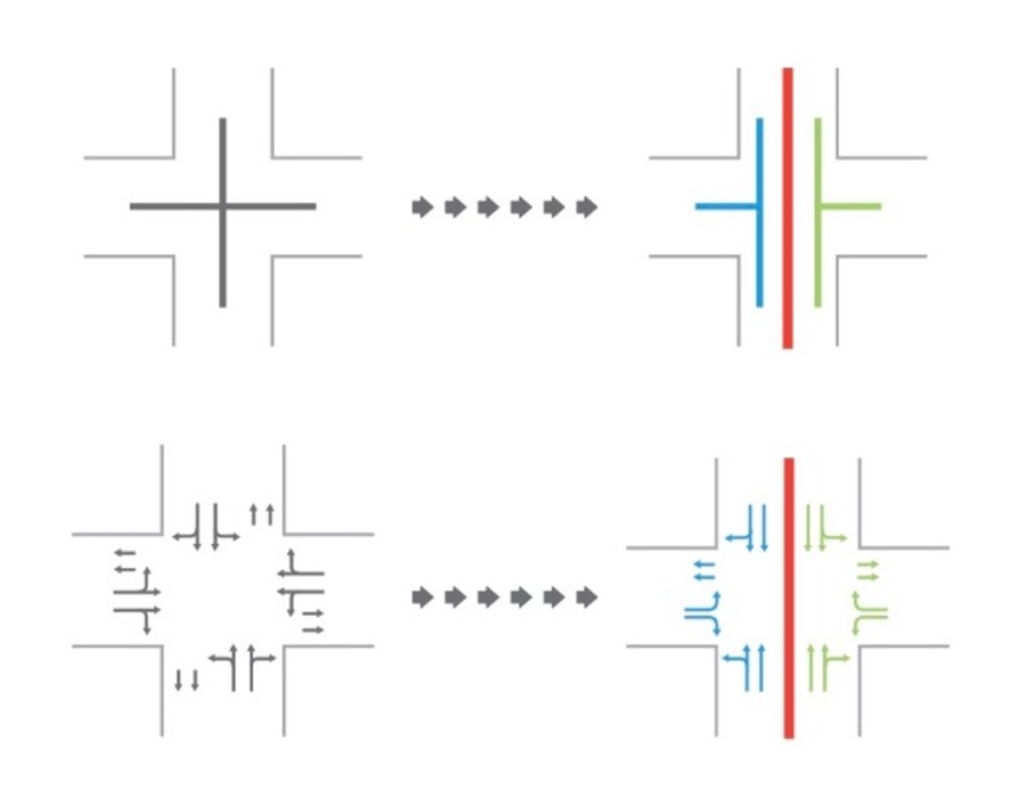

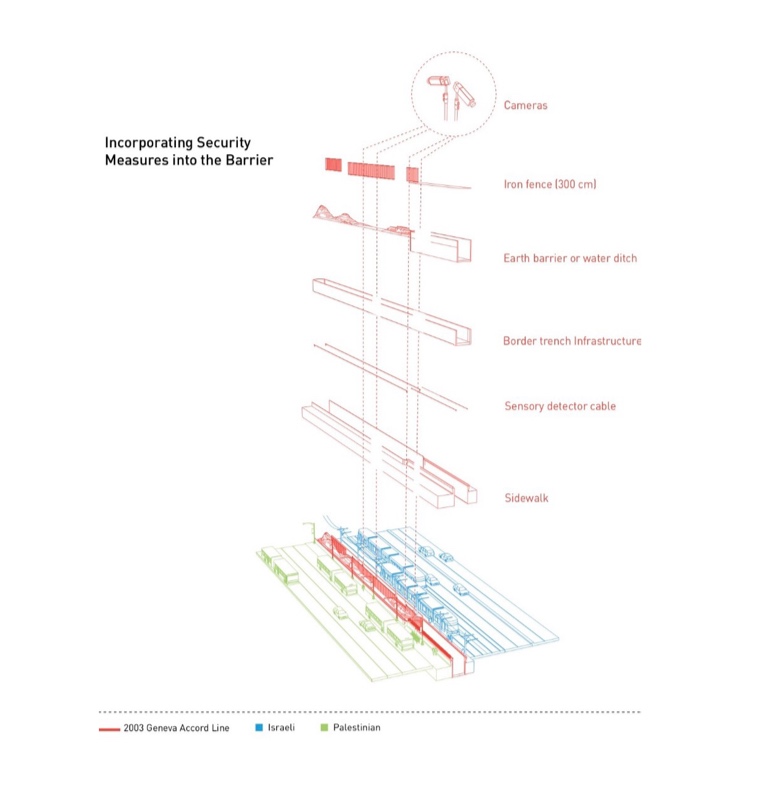

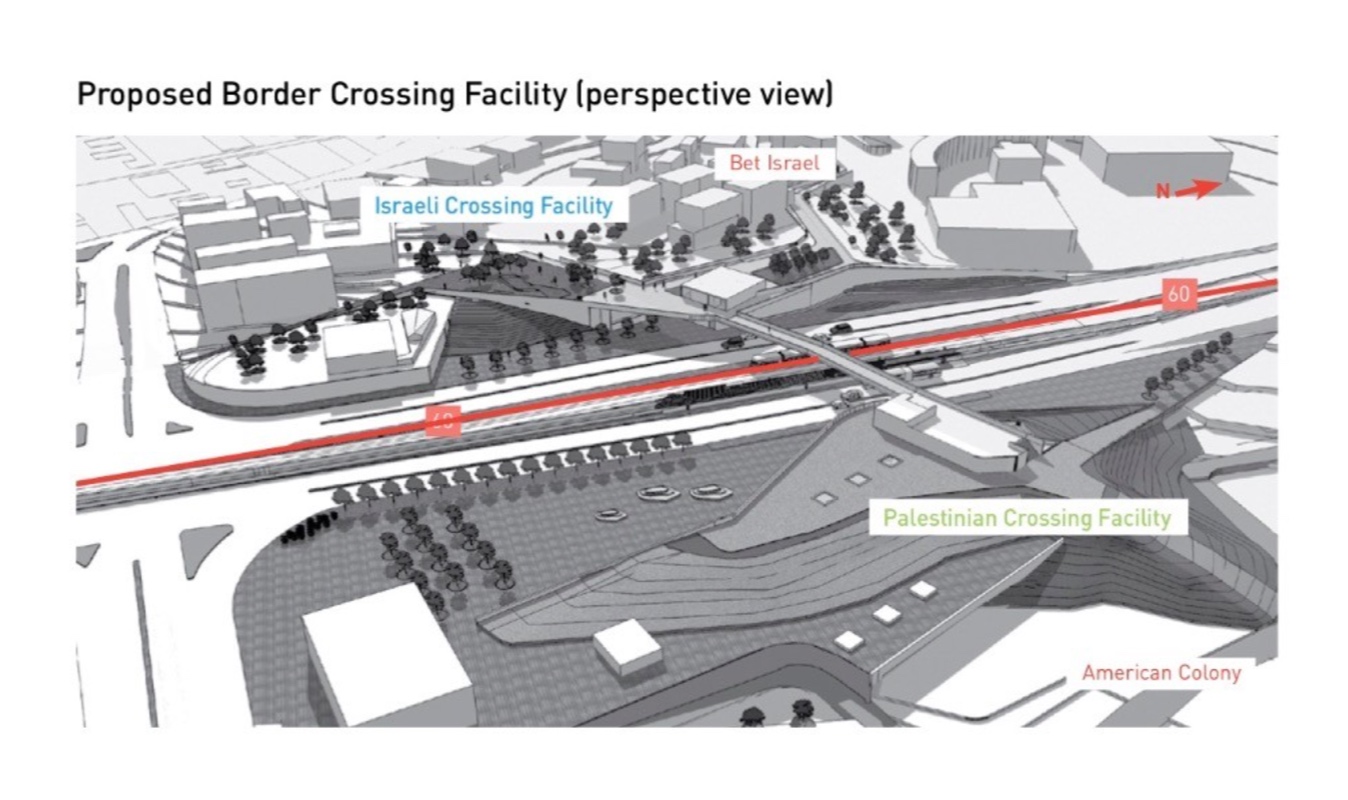

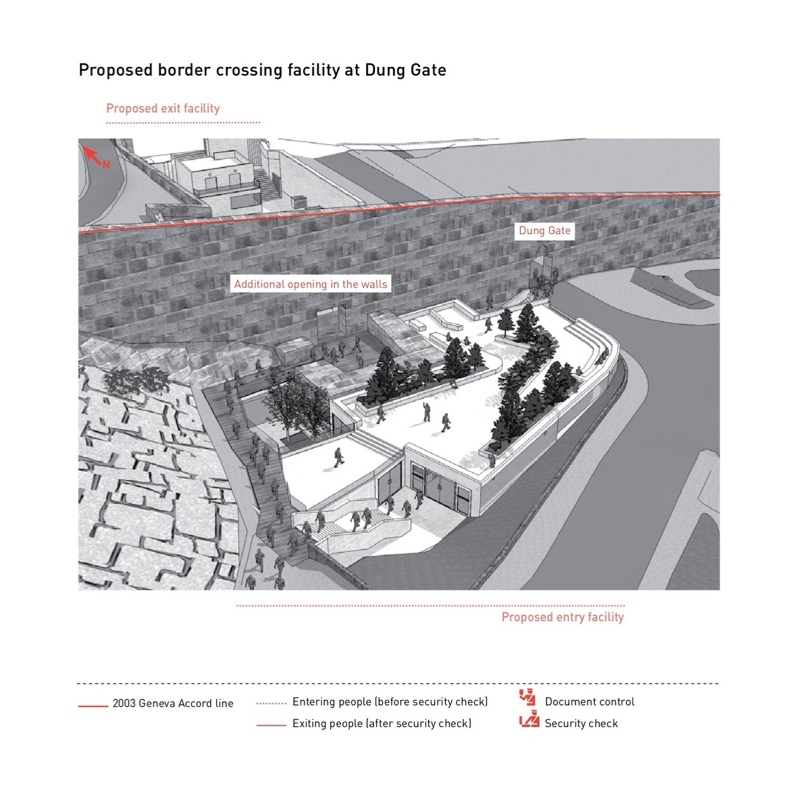

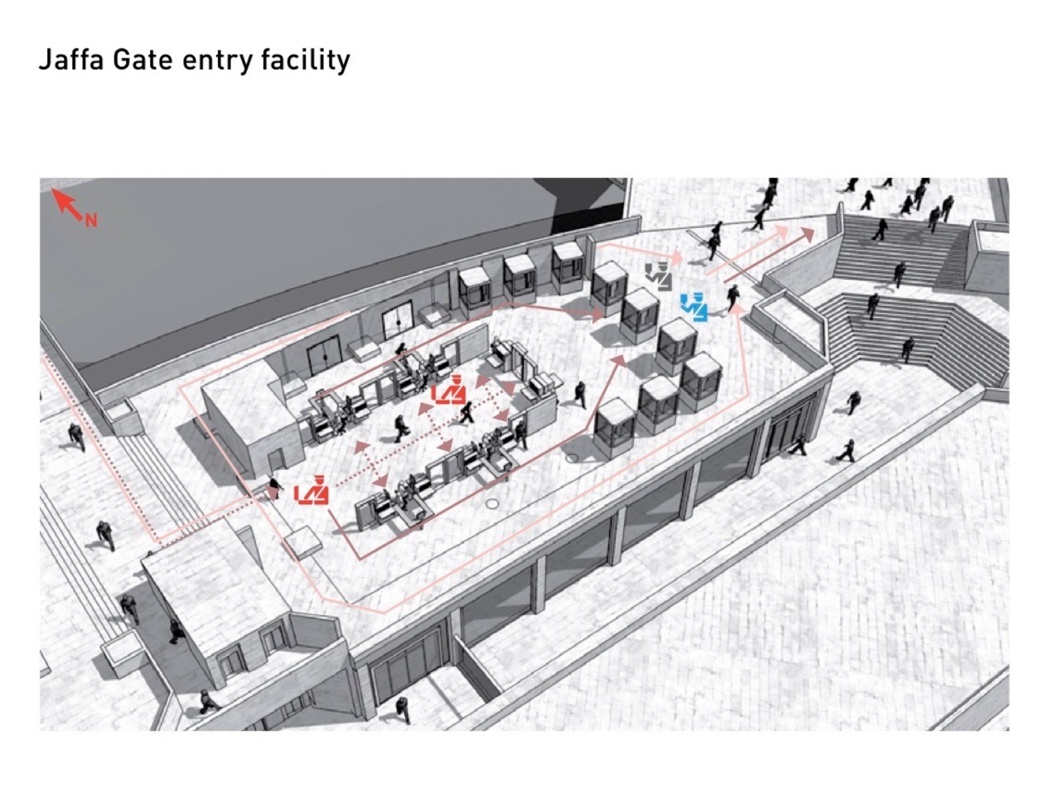

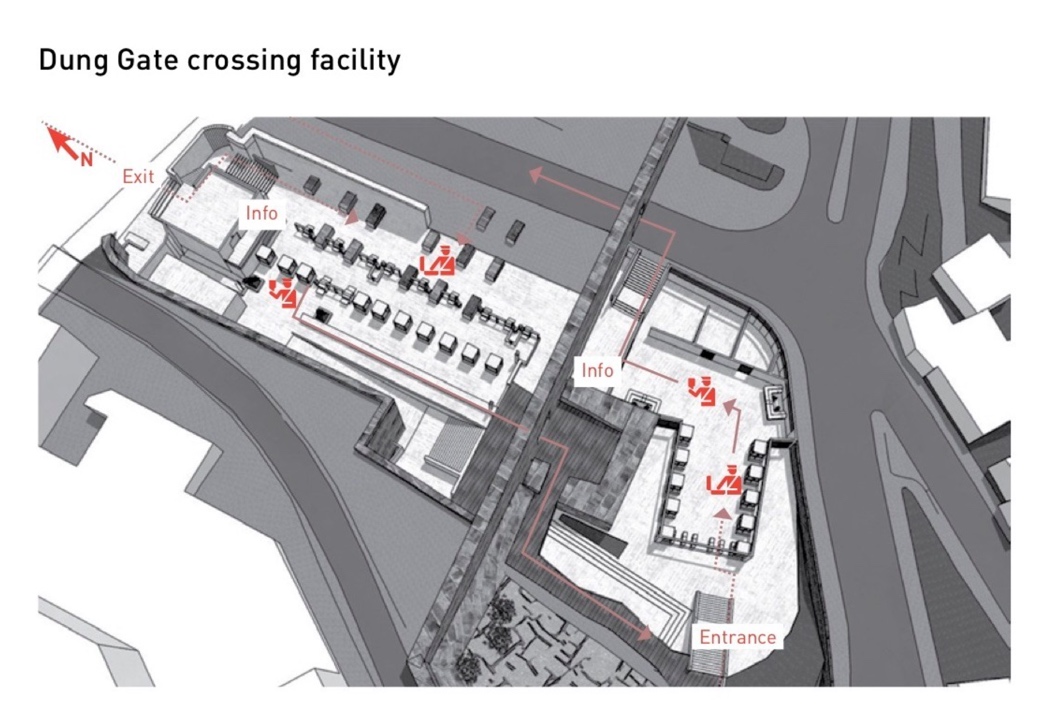

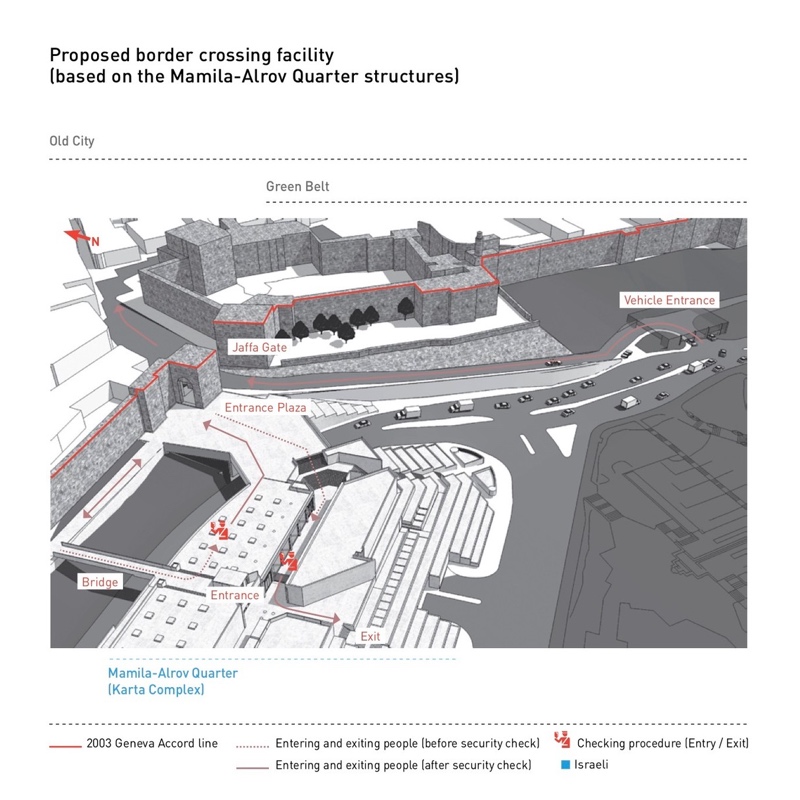

The Geneva Initiative, a joint Israeli-Palestinian civil society effort, proposed a separation barrier that blends in with the built urban landscape. Conceived by the Israeli architecture firm SAYA, the proposal uses familiar urban objects for security measures instead of barbed wire and concrete. Its multi-tiered security infrastructure includes iron fences, trenches, earth barriers, water ditches, cameras, and sensory detector cables. In order to create effective junctions between Yerushalayim and Al Quds, SAYA has proposed channeling people and goods to selected crossings — pedestrians using dense, urban parts, and cars using less crowded, outer areas. One proposed crossing near the American Colony Hotel would create a new link between the urban centers of Yerushalayim and Al Quds. Architectural and technological innovations can thus mitigate the shortcomings of a security barrier — balancing security, commercial, and quality of life considerations.

A Solution for the Old City

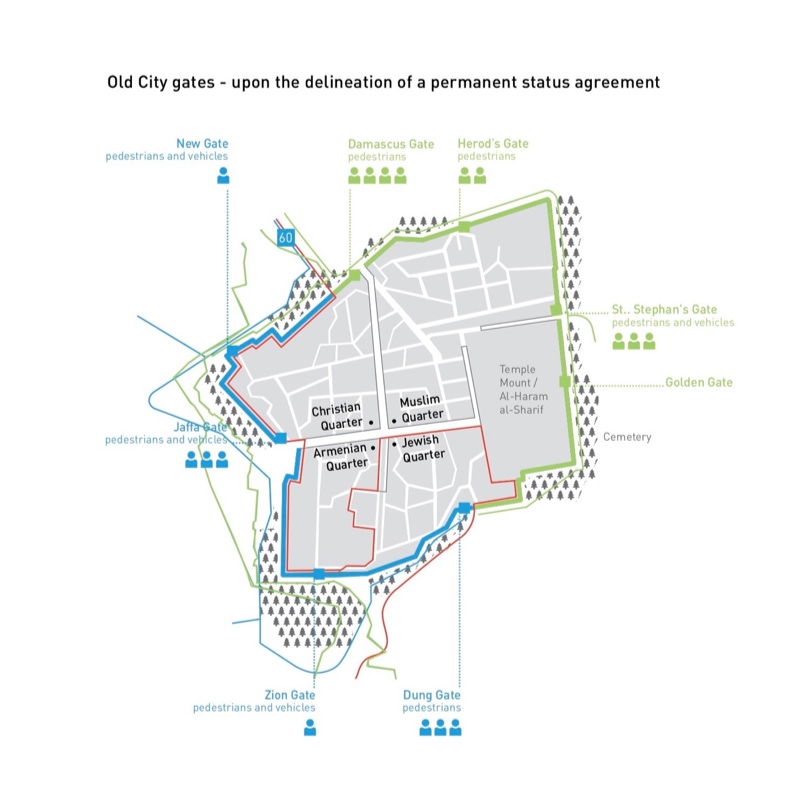

The Old City of Jerusalem is more complicated than municipal Jerusalem. Over 27,000 Muslims, 4,000 Jews, and 7,000 Christians (most of them Palestinian), live in an area of one third of a square mile, divided into the Temple Mount/Haram Al-Sharif, the Jewish Quarter, the Muslim Quarter, the Christian Quarter and the Armenian Quarter. As most Jews in the Old City live in the Jewish Quarter, it might be possible to divide Israelis and Palestinians demographically.

But there would be no clear way to divide the hundreds of significant religious and historic sites located throughout this small area. The Old City is a focal point of Israel’s tourism industry, and likely will be for the future state of Palestine. Any border scheme in or around the Old City must cater to the complex and sometimes contradictory needs of different constituencies.

Old City/Historic Basin and 1967 expanded boundaries

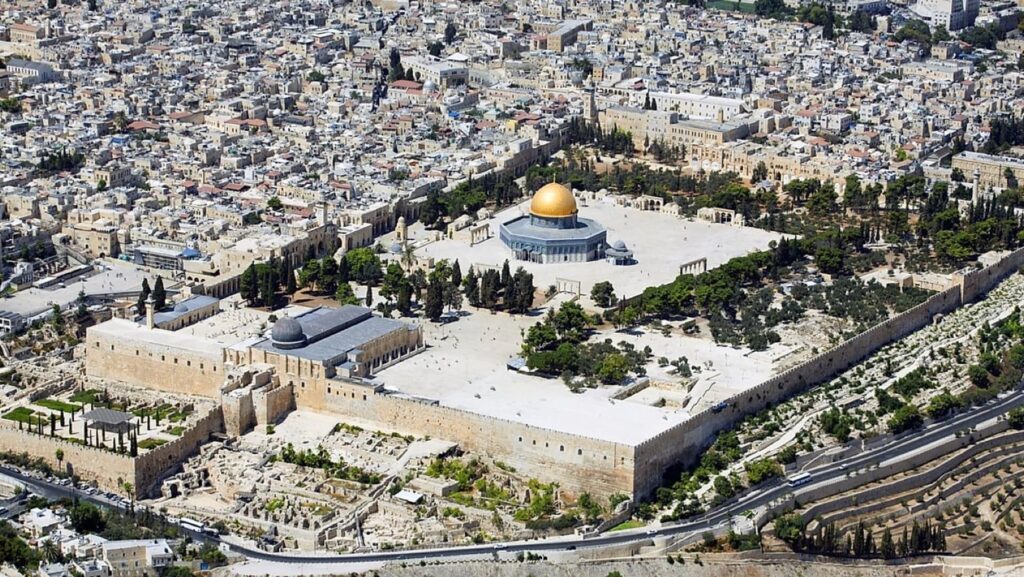

The 37 acre Temple Mount/Haram Al-Sharif is one of the most sensitive areas in the Old City, the site of repeated clashes, and an area of on-going tension. Since 1967, an informal, but recognized “status quo” arrangement has governed the site.

A Jordanian sponsored Islamic religious authority administers the plaza and its institutions and buildings, while Israel exercises overall security control. Palestinian and Muslim worshippers generally have free access, and in normal times tens of thousands of worshippers will gather there during important religious occasions. Israel has imposed limited access restrictions, including on Palestinians, particularly at times of high tension. In adherence to the status quo arrangement, non-Muslims are forbidden from praying at the site.

However, real and perceived fears of changes to the status quo, and occasional provocations, have sometimes led to violence and heightened tensions. At the same time, there is a small, but high-profile and growing movement in Israel to allow Jewish prayer at the Temple Mount, which represents a challenge to the status quo framework that governs the site.

Aerial view of the Temple Mount (Shutterstock)

Israeli Jewish authorities and Israeli security forces have total control over the adjacent Western Wall/Kotel site, which has been significantly expanded and upgraded over the decades since 1967. The Old City’s Christian religious sites, including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre compound, are controlled and administered by church authorities and governed under another set of status quo arrangements.

Transit Points

Any border scheme for the Old City would essentially turn its gates into complex transit points, in some cases even international Israeli-Palestinian border crossings. This is a difficult task given the area’s dense geography and sensitive archeology. SAYA, the Israeli design firm, has proposed numerous architectural solutions to balance the complex logistical and security needs of these crossings with the religious and historical sensitivities of the sites.

Holy/Historic Basin

Although the majority of historic and holy sites lie within the walls of the Old City, some are outside in the surrounding region commonly known as the “Holy Basin” or “Historic Basin.” Limiting a special regime to the Old City gives the regime a natural, pre-existing boundary, within a small space, easily isolated from its surroundings. But excluding the Historic Basin would deny sensitive sites the protection of the special arrangements, create a potential source for future conflict, and miss an opportunity for a richer set of trade-offs at the negotiating table.

Satellite image of Jerusalem

Satellite image of Jerusalem

Left: Satellite image of Jerusalem

Right: Satellite image of Jerusalem

There are various ways to extend the political solution devised for the Old City to the Historic Basin. A territorial approach would construct a physical boundary around the Basin instead of the Old City. A more functional approach would divide the Basin between Israel and the Palestinian state. If implemented wisely, a solution could introduce an added layer of security while minimizing disruption to adjacent Palestinian or Israeli neighborhoods and major Israeli and Palestinian transportation arteries; and limiting the physical separation between included areas and the rest of Jerusalem.

Past Proposals

Throughout previous final status negotiations, the sides presented various proposals outlining solutions to the status of Jerusalem, focused on borders in the Jerusalem area as well as proposals for the Old City and/or the Holy/Historic Basin. The following maps are based on projections by Israeli NGO Terrestrial Jerusalem.

A. Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak (Approximated)

Prime Minister Barak’s Proposal

Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak’s Jerusalem proposal in 2000 follows a divided city model, with the largely Jewish neighborhoods in East Jerusalem (including 70,000 Palestinians in the Palestinian neighborhoods surrounding the Old City) under Israeli sovereignty, and the rest of municipal East Jerusalem under Palestinian sovereignty.

Barak’s proposal for the Old City follows a territorial sovereignty model, where Israel would control the Armenian and Jewish Quarters — including the Western Wall — and the Palestinians would control the Christian and Muslim Quarters — including the Temple Mount.

B. Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert (Approximated)

Prime Minister Olmert’s Proposal

Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert’s proposal in 2008 follows a divided city model for municipal Jerusalem, with Jewish neighborhoods in East Jerusalem (including 13,000 Palestinians) under Israeli sovereignty, and the rest of municipal East Jerusalem under Palestinian sovereignty.

In contrast to Barak’s proposal, Olmert’s uses a special regime model for the Old City and Historic Basin, overseen by an international committee to ensure access for all religions.

C. Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas (Approximated)

President Abbas’ Proposal

Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas’ proposal in 2008 follows an open city model, with most Jewish neighborhoods in East Jerusalem under Israeli sovereignty and all Palestinian neighborhoods under Palestinian sovereignty, with no physical border between them. Abbas insisted that areas with Palestinian residents not fall under Israeli sovereignty. Overall, his position hews close to President Clinton’s December 2000 proposal, though Abbas has avoided public discussions of his compromise formulas on Jerusalem.

Abbas’ proposal for the Old City follows a territorial sovereignty model, with Israel controlling the Jewish Quarter, including the Western Wall, and a Palestinian state controlling the rest of the Old City and much of the Historic Basin, to be overseen by an international committee to ensure access for all religions.

C. U.S. President Trump’s “Peace to Prosperity” Plan

President Trump’s “Peace to Prosperity” Plan in 2020 rejected the division of Jerusalem stating “Jerusalem will remain the sovereign capital of the State of Israel, and it should remain an undivided city.” Israeli sovereignty would extend to the security barrier and the capital of the Palestinian state would constitute the neighborhoods located east and north of the barrier (e.g. Kafr Aqab, Shuafat, Abu Dis). Palestinians residing west of the 1949 Armistice line, but east of the security barrier would have three options regarding their citizenship: become citizens of the State of Israel, become citizens of the State of Palestine, or retain their status as permanent residents in Israel.

The Trump plan is a departure from both Israeli PM Barak and PM Olmert’s proposals which divided Jerusalem roughly along the 1949 armistice line. It also differs from Palestinian President Abbas’ proposal which suggested an open city model for Israelis and Palestinians by putting the entirety of Jerusalem west of the security barrier under Israeli jurisdiction. Furthermore, all of the Old City of Jerusalem would be under Israeli sovereignty though a mechanism would be negotiated creating a Jerusalem-Al Quds Joint Tourism Development Authority and allowing licensed Palestinian tour guides to operate in the Old City.

Under the Trump plan, the current status quo governing Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif in cooperation with Jordan would remain in place.

DIGGING DEEPER

”Palestinian Assessment of the Last Five Year Plan” Center for Palestine Studies – Nur Arafeh

”Sheikh Jarrah Showdown” Terrestrial Jerusalem – Danny Seidemann (Podcast)

”A Walk in The Park” Terrestrial Jerusalem – Danny Seidmann (Podcast)

”Expansion of the National Park in the Visual Basin of the Holy City” Terrestrial Jerusalem

“Jerusalem: Israel’s Eternal Capital” Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs

“Geopolitical Atlas of Contemporary Jerusalem” Terrestrial Jerusalem

“Peace Talks on Jerusalem” Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies

“The Significance of Jerusalem: A Muslim Perspective” Palestine-Israel Journal – Ziad Abu Amr

“The Status of the Status Quo at Jerusalem’s Holy Esplanade” International Crisis Group

“Jerusalem Population” Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research – Yair Assaf-Shapira

“The Border Regime for Jerusalem in Peace” Saya Design for Change

“Jerusalem Atlas” Terrestrial Jerusalem

“Jerusalem Annex” Geneva Initiative

“Al-Haram al-Sharif/ Temple Mount Compound” Geneva Initiative

“Jerusalem Old City Initiative” Windsor University

*These materials are provided for reference purposes, with no intention of endorsement.