Demographics

“Demographics,” often a codeword for ensuring a Jewish majority, is a significant concern for many Israelis. Viewed as essential to maintain the country’s Jewish character, demography has increasingly become a centerpiece of Israeli public discourse and debates about peacemaking. It is also of growing importance in debates across the Jewish diaspora.

BACKGROUND

Demography and the notion of a “Jewish majority” has long been a central feature of Zionist thought. “To be a free nation, in our own land,” the core idea expressed in Israel’s national anthem, Hatikva, has long been understood to place demographics on an equal par with geography and territory. Early Zionist leaders, like David Ben Gurion, placed as much emphasis on securing land for a Jewish state as on maintaining a Jewish majority, seen as a crucial foundation for building a political community that would allow Jews to escape the marginalization and exclusion that defined most Diaspora communities. During Zionism’s early decades, before the establishment of the state, as hostility grew between Jewish and Arab communities, demographics would only grow in importance.

Demographics have also been a key consideration in diplomatic approaches, including peace frameworks like the U.N. partition plan (November 1947), which drew borders for two independent states, one Jewish and one Arab, based on a mix of considerations, including demography, territorial contiguity, and economics.

Map of the U.N. Partition Plan (Jewish virtual library, 1974)

Given the country’s acute strategic vulnerabilities in its early decades—whether it be the threat of conventional war from Egypt, Syria, and other neighbors or the steady stream of terrorist attacks Israelis faced—territory and “defensible borders” took on a more significant role in national security and diplomatic thinking.

These vulnerabilities began to erode, particularly following the peace treaties with Egypt and Jordan and also in the aftermath of the First Intifada (1987-1991), which sparked a deep reckoning in Israel and convinced many Israelis that the country could not control Palestinian territories indefinitely.

Nefesh B’Nefesh (Shahar Azran, 2016)

DEMOGRAPHY AND MODERN ZIONISM

For decades, Zionists argued that time was on Israel’s side and that through natural population growth and Aliyah (immigration) and by reaching a negotiated settlement with Palestinians, a comfortable Jewish majority could be maintained for the foreseeable future. Demographics (i.e., maintaining a Jewish majority) and “separating” from the Palestinians were a major rationale for Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin for negotiating what came to be known as the Oslo Accords.

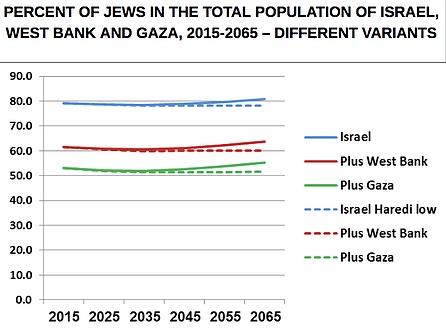

Percent of Jews in the total population of Israel. West Bank, and Gaza, 2015-2065 (Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics)

But following the collapse of Oslo and the trauma of the Second Intifada, the debate shifted dramatically, and many Jewish Israelis began to fear that time and demographics were working against Zionism. These sentiments led to PM Sharon’s “disengagement” from Gaza in 2005 and the removal of Israeli settlements from the densely populated Palestinian territory. Many Likud figures, including former Foreign Minister and Justice Minister Tzipi Livni, joined Sharon and broke with their party in order to support various frameworks for unilateral withdrawal and territorial compromise.

Prime Minister Ariel Sharon with later Prime Minister Ehud Olmert (Sharon Perry/Flash90, 2014)

After Sharon was incapacitated by a stroke, his successor Ehud Olmert promoted an even bolder plan, which he called “convergence” or “realignment.” Olmert’s plan, which was adopted by the Israeli government in 2006, sought to “shape the permanent borders of the State of Israel as a Jewish state, with a Jewish majority, and as a democratic state.” It was based on a preference for a negotiated two-state solution, but if that was not possible, then Olmert pledged that his “Government will take action even in the absence of negotiations and agreement with (the Palestinians).”1 See Guidelines of Israel’s 31 st Government, https://www.mfa.gov.il/mfa/aboutisrael/state/government/pages/basic%20guidelines%20of%20the%2031st%20government%20of%20israel.aspx. For further background on Olmert’s plan, see http://www.reut-institute.org/Publication.aspx?PublicationId=338 Olmert’s plans did not succeed and the Likud party, now under Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, returned to power in 2009.

CURRENT SITUATION

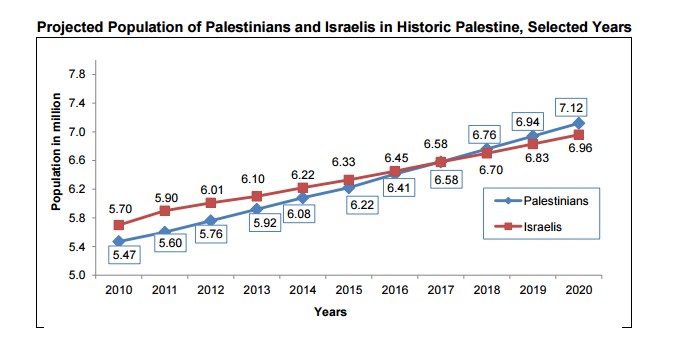

Although Jews represent about 75 percent of Israel’s population, when including the Palestinian territories, the split is closer to 50/50. The Jewish population in 2020 is just under seven million, and the Palestinian Arab population in Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza is estimated at around six million.2 See Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics, https://www.cbs.gov.il/en/mediarelease/pages/2019/population-of-israel-on-the-eve-of-2020.aspx, and CIA, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/. For further information, see https://www.ispeacestillpossible.com/copy-of-threats-and-helpful-realiti Demographics is yet another battleground in the Israeli-Palestinian debate, and some advocates contend that the Palestinian population is much smaller, though these calculations have been debunked by leading demographers.

Chart by Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics

Most Jewish Israelis, and the majority of Jewish American leaders, continue to worry that once Jews no longer constitute a clear majority in the territory under Israeli control, then either Israel’s Jewish character or its democracy will be inexorably compromised. By this logic, if Israel were to rule over a non-Jewish majority or near majority without granting equal rights, then Israel would no longer be a democracy. But if Israel were to grant full democratic rights to Palestinians, then Israel would transform into a binational state and no longer be a Jewish state.

Therefore, many have argued that in order for Israel to maintain its Jewish majority and democracy, it must relinquish control over Palestinian territory. But there are profound disagreements about how to relinquish control. For more than a decade, Prime Minister Netanyahu has generally opposed relinquishing Israeli control and places less emphasis on demographics, though at different junctures, he has reticently accepted the notion of a two-state solution under certain conditions.

Israelis who dismiss demographic warnings argue that Gaza should not be included in calculations since Israel already withdrew, and West Bank Palestinians already have voting rights under the Palestinian Authority. Some Israelis are calling for the resettlement of the Gaza Strip for political, religious, and security reasons which would potentially reintroduce a large Palestinian population into the demographic mix.

Some even promote the idea of re-drawing Israel’s borders to reduce the size of the country’s Arab population, ideas generally viewed as antidemocratic and deeply controversial.3 Non-Jewish Israelis, particularly the approximately 20% of the population that is Arab, generally reject demographic-driven frameworks and instead promote a political platform based on citizenship, civil rights, and equality.

Digging Deeper

”Israel Approaches 9.5 Million Residents on the Eve of 2022” The Times of Israel – Amy Spiro

”World Jewish Population” The Hebrew University – Sergio DellaPergola

”Israel: A Jewish, Democratic and Secure State” The Jerusalem Post – Jermy Saltan

”The 2019 Election – The Rise of the Far-Right” The Jerusalem Post – Jermy Saltan, Joel Braunold

*These materials are provided for reference purposes, with no intention of endorsement.