Security

Security is fundamental to the resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Until security for both Israelis and Palestinians is addressed and demonstrated, leaders will not have the political capital required to resolve the other core issues of the conflict. Moreover, in a regional dynamic of shared interests and common threats, the security of Israelis and Palestinians can affect the entire Middle East, and vice-versa.

October 7th Update

The attack launched by Hamas on October 7th has forced Israel to reconsider its security and intelligence paradigms. The attack was a catastrophic security and intelligence failure not only due to its far-reaching damage and loss of life, but also because the equipment used by Hamas to perpetrate the heinous attack was not particularly sophisticated or specialized. In limited discussions of a post-war Gaza much of the Israeli side of the conversation has focused on security concerns including the creation of a larger buffer zone between Israel and Gaza and a military presence between Egypt and Gaza.

The need for a territorial buffer for Israelis’ peace of mind has also extended to the northern border with Lebanon following Hezbollah’s attacks in the north. As of March 2024, the conflict on the northern border has remained somewhat limited. Some Israelis are promoting diplomatic efforts to push Hezbollah back to north of the Litani River to prevent full-scale war – at least in the short-term. However, the previous security paradigm of having Hezbollah and IDF forces in close proximity to one another is no longer acceptable to the thousands of Israelis who have been evacuated from their homes since October 7th and will not return with Hezbollah on their doorstep.

Beyond the threats posed by Hamas and Hezbollah on Israel’s southern and northern borders, many Israelis fear another front opening from Palestinians in the West Bank, though, at this point violence has remained limited.

Lurking behind the rising tensions in the region is Iran which has been funding and providing military support to Hamas, Hezbollah, Ansar Allah (Houthis), and other terrorist groups. Any long-term regional stability would need to deal with the Iranian threat.

QUESTION

Can an agreement satisfy Israel’s security requirements and Palestinian demands for a viable, contiguous and sovereign state?

President Bill Clinton Parameters map (2000)

ISRAELI PERSPECTIVE

In its early years, Israel confronted conventional ground invasions from neighboring Arab states, as well as Palestinian fedayeen militia who rejected Israel’s right to exist and threatened to “drive the Jews into the sea.” Israelis were encircled by enemies, and felt exposed by the country’s limited territory, especially at its “narrow waist” in the country’s center, north of Tel Aviv.

Since then, a number of factors have all but eliminated the threat of invasion and conventional military attacks: Israel’s Qualitative Military Edge (QME) (guaranteed by the U.S.), land buffers in the West Bank and Golan Heights, peace agreements with Egypt in 1979 and Jordan in 1994 (and those countries’ alliances with the U.S.), and Iraq’s military defeat and its diminished capability to threaten its neighbors.

As a result of these peace agreements, Israel’s security focus turned to Palestinian terrorist threats. Though terrorism was not a new phenomenon for Israelis, it increased dramatically in the mid-1990s, and again during the second Intifada (2000-2005), when Israelis faced waves of mass-casualty suicide bombings. From 2005 until 2023, no large-scale waves of terrorism have occurred. Instead, Israel faced the increased threat of smaller-scale “lone-wolf” Palestinian attacks. The impact of these individual attacks is still significant across Israeli society.

The one exception before October 7th was the inter-communal violence in May 2021 between Jewish and Arab communities within Israel. In the first half of 2021, tensions rose due to a contentious dispute over property ownership in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem and confrontations between Palestinians and Israeli police in the al-Aqsa compound. In mid-May, these tensions boiled over resulting in rocket fire from Gaza and mass protests in the West Bank. Furthermore, there were riots within mixed Jewish-Arab cities including Lod, Ramle, and Haifa. These riots brought up fears for Israelis of a large enemy population living as citizens or residents within Israel.

Defense systems and threats

Bombed Israeli bus (Wikimedia Commons)

Left: Defense systems and threats

Right: Bombed Israeli bus (Wikimedia Commons)

In the 21st century, conventional threats to Israel have largely been replaced by asymmetrical ones, including aerial attacks — rockets, short-range missiles, and aircraft, including drones. Israelis are threatened in the south by rocket fire from terrorist groups in the Gaza Strip and Sinai Peninsula, and in the north, by Hezbollah and other terrorist groups in Lebanon and Syria, many backed by Iran. Technological advancements have also put Israel within striking distances of medium and long-range ballistic missiles, with Iran posing the most serious threat. To confront these threats, Israel and the United States have jointly developed cutting-edge missile defense systems: Iron Dome, David’s Sling, and Arrow 3.

Technological advancements have also put Israel within striking distance of medium and long-range ballistic missiles, with Iran posing the most serious threat. To confront these threats, Israel and the United States have jointly developed cutting-edge missile defense systems: Iron Dome, David’s Sling, and Arrow 3. Israel has conducted air strikes against Iranian targets in Syria to disrupt the transfer of key Iranian personnel, weapons, and military technology for precision-guided missiles.

Until October 7, 2023, Israel operated by a military doctrine that believed it was possible to contain threats on its southern and northern borders with a combination of political arrangements, high-tech intelligence and defense systems, and the threat of a powerful Israeli response. This doctrine of containment proved to be successful with only a handful of significant military operations between 2005 and 2023 (e.g. the Second Lebanon War in 2006, Operation Cast Lead in 2008, Operation Pillar of Defense in 2012, and Operation Protective Edge in 2014).

An Israeli Iron Dome anti-rocket system, right, and an American Patriot missile defense system during a joint U.S.-Israeli military exercise (Jack Guez/AFP, 2018)

However, this doctrine was overturned on October 7, 2023, when Hamas launched an unprecedented invasion of Israeli border communities. The attack was preceded by a barrage of rockets from Gaza which served as cover for almost 3,000 militants who broke through the security barrier. The Hamas militants using trucks, motorcycles, cars, and paragliders quickly reached many Israeli civilian communities, military bases, and a music festival. These communities and military bases were caught off guard and upon reaching them the Hamas terrorists proceeded to murder almost 800 civilians and 400 security forces, injure another 3400, and kidnap 247. By the end of October 8th, the IDF had regained control of all communities and bases taken by Hamas.

In late November 2023, after several weeks of airstrikes, Israel began its ground invasion of Gaza aimed at returning the hostages and destroying Hamas’ military capacity. Tensions have remained high on Israel’s northern border and many of the communities have been evacuated in anticipation of a full scale conflict with Hezbollah. Though, as of March 2023, this has not occurred.

Though there are few concrete details about a security arrangement for Gaza following the conclusion of the ongoing war, Israel has indicated that it would likely include an expanded buffer zone on the Israel-Gaza border as well as an Israeli military presence between Egypt and Gaza. The latter security force would operate “as much as possible in cooperation with Egypt and with the assistance of the U.S.”

Another ongoing security threat is Hezbollah as Israel and Hezbollah have been engaged in a limited war since October 7th. As of March 2024, almost 300 Hezbollah militants, over 10 Israeli soldiers, and 6 civilians have been killed and tens of thousands have been displaced.

Talks are ongoing between Israel and Hezbollah mediated by US envoy Amos Hochstein to negotiate a temporary or long-term ceasefire or at least to move Hezbollah forces away from the Israel-Lebanon border. The threat of an escalation between Israel and Hezbollah could spell a significant increase in regional conflict as Hezbollah is more directly backed by Iran than Hamas and has stockpiles of tens of thousands of precision-guided missiles. Some experts say that Hezbollah has approximately 100,000 rockets – ten times more than Hamas’ arsenal.

A picture of a destroyed Palestinian Islamic Jihad tunnel, leading from Gaza into Israel, near the southern Israeli kibbutz of Kissufim (Jack Guez/AFP/Pool, 2018)

PALESTINIAN PERSPECTIVE

Though security is often framed as an Israeli concern, a future state of Palestine would be affected by many of the same threats, and would have a shared interest in countering them. However, many Palestinians have become convinced that Israeli security comes at their expense. In the West Bank and Jerusalem, Palestinians perceive that they are often subjected to wrongful arrests, and at times, violence, by Israeli forces. In addition, many Palestinians fear Israeli settlers and numerous instances of settler violence and vigilantism against innocent Palestinians have occurred.

Palestinians lined up at an Israeli checkpoint (Shutterstock)

Israeli soldiers check Palestinian cars at a checkpoint near the West Bank (Reuters, 2015)

Left: Palestinians lined up at an Israeli checkpoint (Shutterstock)

Right: Israeli soldiers check Palestinian cars at a checkpoint near the West Bank (Reuters, 2015)

In the Gaza Strip, Palestinians fall victim to air and drone strikes aimed at terror groups. In light of the Israeli and Egyptian closures and restrictions, Gazans also feel a particularly acute sense of isolation and insecurity. In the West Bank, Palestinians feel their dignity and livelihoods are damaged by security checkpoints, military zones and the security barrier and feel helpless against Israeli authorities and settlers.

Since Israel took control of the Gaza Strip, West Bank, Golan Heights, and East Jerusalem in 1967 to various degrees, Palestinians have confronted the Israeli presence in a variety of ways including popular protests and violence such as in the First Intifada (1987-1990) and Second Intifada (2000-2002).

Having experienced the peace process drag on indefinitely, Palestinians seek a rapid Israeli disentanglement from their daily lives – a fact that has only become more apparent since October 7th. Thus, from a Palestinian perspective, accommodating Israeli security in a peace agreement must meet Palestinian security needs and not compromise a genuine sense of Palestinian sovereignty and statehood.

Weighing Israeli security vs Palestinian sovereignty

ASSESSING THE STATUS QUO

One perspective of Israeli security is the strategy of “territorial strategic depth.” Victory in the 1967 War gave Israel full control of Jerusalem, the West Bank, Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights, and the Sinai providing a territorial buffer against conventional attacks from neighbor states.

From 1967 until 1993, the Israeli military oversaw the administration of Palestinian life in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem and built a security apparatus to safeguard Israelis and the new settlements established in the territories. These measures included roadblocks, checkpoints and intervention into Palestinian villages which diminished the Palestinians’ sense of security.

In 1993, the Oslo Accords created a framework for limited Palestinian governance under a new Palestinian Authority (PA). This was intended to be temporary, with final-status talks to follow. To combat terrorism and other threats, the Accords established Israeli-Palestinian intelligence sharing and security coordination, and since then, PA forces have maintained internal security over most Palestinian cities. Still, Israeli forces continue some limited operations into Palestinian population centers, which the Palestinians call “incursions.”

Palestinian Authority (PA) security forces enter the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Kafr Aqab (Twitter, 2021)

Oslo Accords Map (1993)

Left: Palestinian Authority (PA) security forces enter the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Kafr Aqab (Twitter, 2021)

Right: Oslo Accords Map (1993)

This overall arrangement is assisted by an international security training mission led by the United States. With support from Congress, this mission acts as a liaison to security chiefs on all sides, and conducts professional training programs for Palestinians.

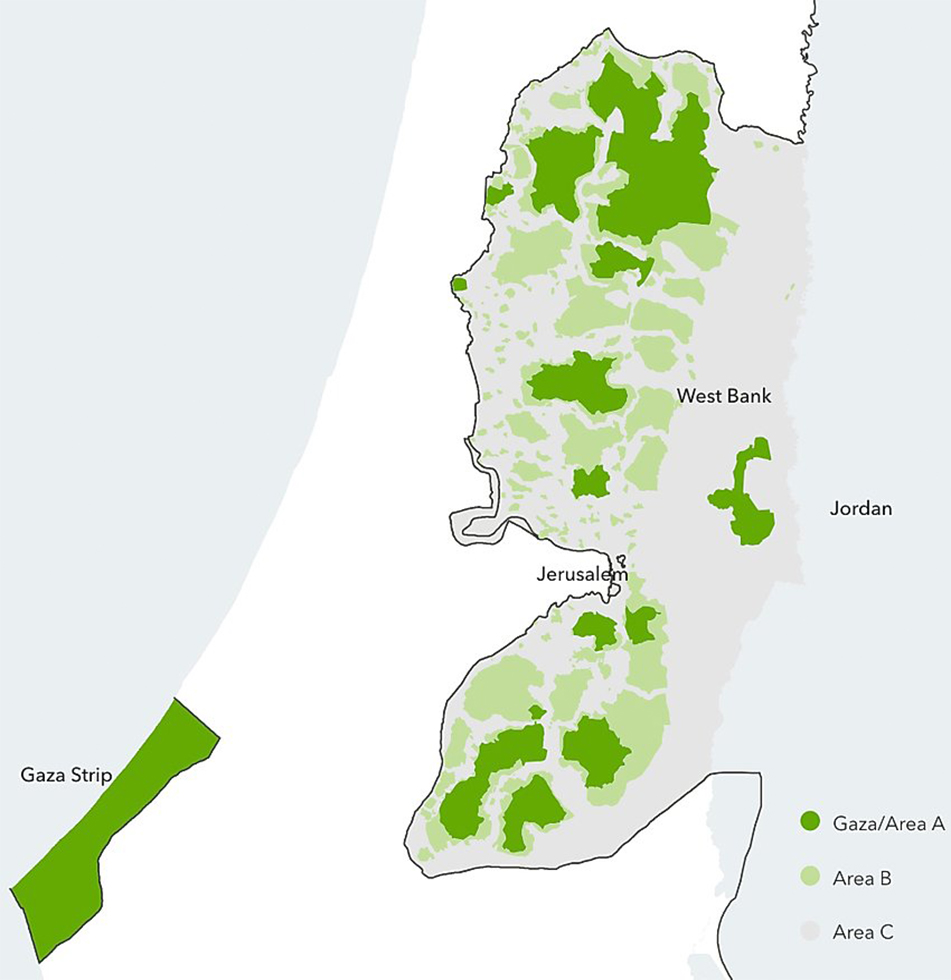

The Oslo Accords divided the West Bank into three areas:

Area A (18%): PA civil and security control in Palestinian cities;

Area B (22%): PA civil control and Israeli security control; and

Area C (60%): Israeli control over remaining Palestinian areas, as well as settlements, major roads, national parks, military zones, and the border with Jordan.

Most Palestinians reject the territorial approach to security because they feel that Israel’s presence in the West Bank threatens their own security and inhibits the establishment of a viable, contiguous, and sovereign Palestinian state.

Many Israelis continue to support the territorial approach, arguing that it gives Israel maximum flexibility to combat terrorism, guard the Jordanian border, and provide security for settlements. They contend that Israel’s borders without most of the West Bank would be “indefensible”.

However, some of the fiercest arguments against the territorial approach come from Israel’s security establishment. Defense experts note that Israel won two wars in 1949 and 1967 without a West Bank land buffer, and since then, Israel’s Qualitative Military Edge (QME) has increased, and the strategic advantages of holding territory have decreased. Experts argue that control of the West Bank harms counterterror efforts more than it helps — fueling Palestinian hostility, and undermining the Palestinian Authority and Palestinian moderates. In the long-run, this delicate balance could prove unsustainable, forcing Israel to retake financial and security responsibility for West Bank Palestinians.

Moreover, Israel’s control of the West Bank complicates its relations with its Western allies and is used as an excuse by extremists around the world to incite hostility against Israel.

Israeli forces in the West Bank (Reuters)

Lastly, many Israeli defense experts argue that in addition to the security costs of Israel’s military presence in the West Bank, there is an even greater cost from its civilian presence, the expanding Israeli settlement enterprise. One major study by Molad—the Center for the Renewal of Israeli Democracy—concluded that settlements, especially the many outposts deep in the West Bank, stretch out the military’s lines of defense, requiring a disproportionate investment in settlement protection. Although settlers make up only five percent of Israel’s population, nearly half of Israeli forces are tasked with their defense.

HELPFUL REALITIES

In a major concession to Israel, Palestinian President Abbas has publicly agreed to a “non-militarized” Palestinian state. The new state could maintain internal security through a police force trained and equipped by the U.S., without possessing an army, navy or air force that could pose a potential threat to Israel.

Abbas has also agreed to restrictions on military alliances with countries or groups hostile to Israel, and on allowing outside armed forces to secure a foothold in a future Palestinian state.

Security proposal by the Center for New American Security (CNAS)

Perhaps most importantly, making progress on the Palestinian issue could transform Israel’s regional security position by further warming relations with its Arab neighbor states. Through the Arab Peace Initiative, all 22 members of the Arab League, and 57 members of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, have committed to normalizing relations with Israel following an Israeli-Palestinian agreement. Regional normalization could cement the growing security ties between Israel and the Gulf states, and present many new opportunities, including joint missile-defense, intelligence sharing, joint military training and operations, and cooperation against Iran, Islamic extremism and other common threats.

To be sure, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is not the principal driver of instability in the Middle East. That said, progress towards its resolution would likely weaken extremists, strengthen moderates throughout the region, and advance U.S. strategic interests as well.

October 7th has changed the status quo of many paradigms in the region including that of Palestinian statehood. As a result of October 7th, the US and some Arab countries have sought to end the current conflict by implementing a pathway toward Palestinian statehood. For many Israelis, this pathway is an anathema that would “reward” Palestinians for terror. Furthermore, from an Israeli perspective, any peace agreement must not diminish Israel’s ability to protect itself, by itself — and ideally should strengthen Israel’s capabilities and the population’s sense of security. Israelis worry that establishing a Palestinian state in Gaza and the West Bank could result in an attack similar to October 7th albeit on a much larger scale as the West Bank sits close to many of Israel’s most populated areas.

One potential upside of such an agreement for Israel could be that Saudi Arabia would agree to normalize relations with Israel. This would further enmesh Israel in an important strategic alliance aimed at defending itself from Iranian threats.

To be sure, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is not the principal driver of instability in the Middle East. That said, progress towards its resolution would likely weaken extremists, strengthen moderates throughout the region, and advance U.S. strategic interests as well.

CHALLENGES

As a direct result of October 7th, the prospect of an Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank is a non-starter for the Israeli military establishment and many Israelis. They fear a similar attack coming from the West Bank which would be even more devastating as the West Bank sits close to many of Israel’s population centers. That being said, several questions would need to be addressed in any negotiated agreement in the aftermath of October 7th.

How quickly would Israeli troops withdraw from the West Bank?

In past negotiations, Palestinians have stressed that Israeli withdrawal should have a set timeframe, and they have argued for a transition of no more than two to five years.

Israel insists on a lengthier transition, perhaps lasting decades, dependent on Palestinian security effectiveness. PM Netanyahu has promoted the idea of an indefinite presence in the Jordan Valley and elsewhere in the West Bank.

The West Bank settlement of Ganim in 2005, the land where Ganim once stood in (Emil Salman/Getty, 2017)

How would Israel counter threats within the West Bank in an emergency?

Israel demands the right of unilateral intervention, should the security situation warrant it.

The Palestinians have opposed an open-ended allowance for such contingencies, which they consider to be an incursion on their sovereignty.

Israeli security forces at the entrance to the village of Qabatiya in Jenin (Haytham Shtayeh/FLASH90, 2016)

What would prevent invasion or infiltration from the Palestinian border with Jordan?

The Palestinians have opposed a long-term Israeli force, seeing it as undermining Palestinian sovereignty. However, they have been open to a multinational force in the Jordan Valley.

Israel has little confidence in the effectiveness of a multinational force, and insists on maintaining its own long-term presence in the Jordan Valley.

Israel’s Airports Authority operates the Allenby Bridge crossing allowing Palestinians who are banned from flying from Ben Gurion Airport to cross over into Jordan and depart from Amman. At the urging of former U.S. Ambassador to Israel Tom Nides and the Biden administration, the Allenby crossing was opened for full service in April 2023.

The Allenby Bridge border crossing between Jordan and Israel (Shay Levy/FLASH90, 2020)

Who would guard Palestinian coastline and airspace?

Israel has pushed for control of both to prevent infiltration by terrorists or hostile forces. The Palestinians have strongly disagreed.

Palestinians prepare incendiary balloons near the city of Jabalia in the Gaza Strip (Hassan Jedi/FLASH90, 2019)

NARROWING THE CONFLICT

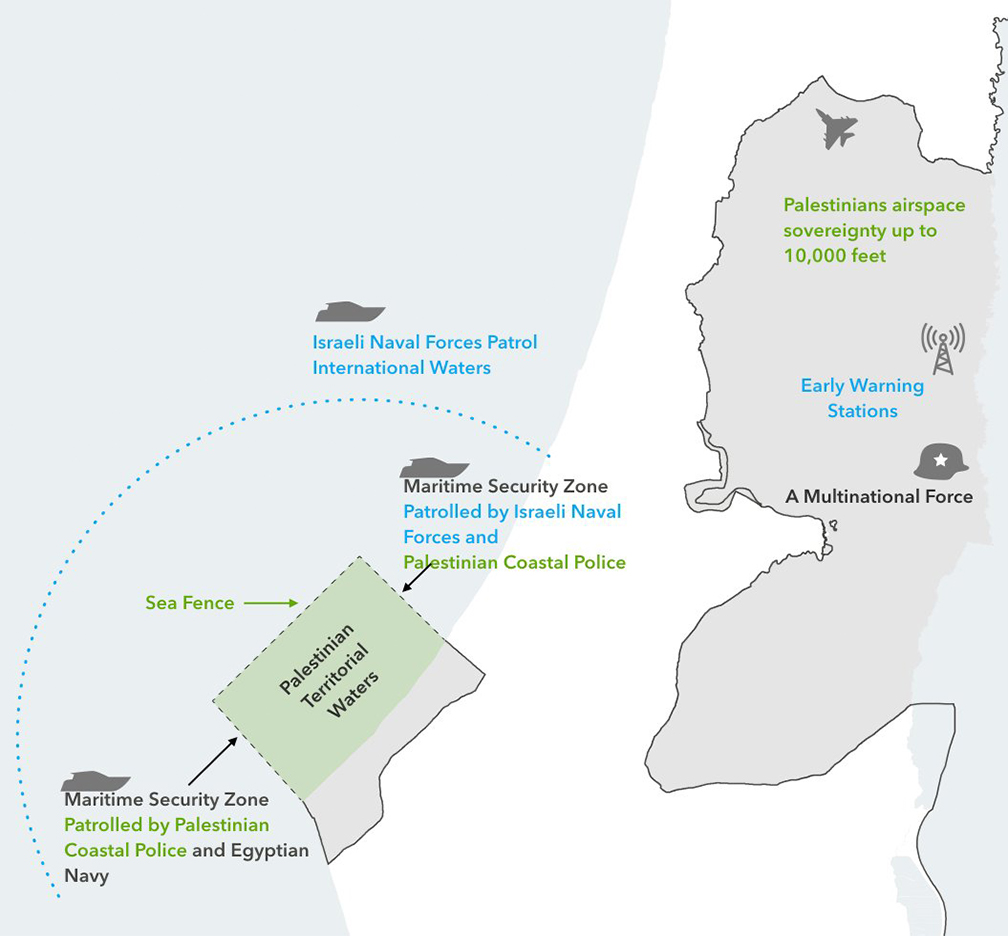

Instead of the territorial approach, Israeli-Palestinian negotiations have explored how a multi-layered security approach could better address the Israeli need for security and the Palestinian need for sovereignty.

The Washington-based, bipartisan Center for New American Security (CNAS) published a 2016 report titled, “Security System for a Two-State Solution,” based on still classified efforts of the 2013- 2014 U.S.-led initiative under the command of Gen. John Allen. This multi-layered approach provided the following security details:

How quickly would Israeli troops withdraw from the West Bank?

A phased process over 10 – 15 years, based on performance benchmarks for the Palestinian forces. Disputes would be resolved by a task force of Americans, Israelis and Palestinians.

How would Israel counter threats within the West Bank in an emergency?

Intelligence cooperation between Israel, the Palestinians, the U.S., Jordan, and Egypt would identify threats and coordinate a response from the Palestinian counter-terror force, with the option of Israeli counter-terror and air support. Suspects would be detained and prosecuted by a joint Israeli-Palestinian counter-terror mechanism.

If Israeli and Palestinian officials disagree on the proper response, a side agreement with the U.S. would guarantee American support for Israeli unilateral intervention under certain criteria.

What would prevent invasion or infiltration from the Palestinian border with Jordan?

Initially, Israelis would control the border, but with a less visible presence. Later, a U.S.-led multinational force could guard the border, bolstered by Palestinian security forces with Israeli remote monitoring and early warning stations and sensors in the West Bank. A limited, independent Israeli force could also be possible.

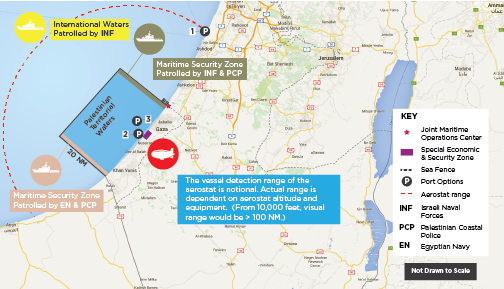

Who would guard Palestinian coastline and airspace?

Palestinians would have airspace sovereignty up to 10,000 feet in altitude, so that Israel could defend both states from aerial attacks without interfering with Palestinian aviation.

In the Mediterranean, the Palestinians could have a seaport —potentially on a man-made island several miles from the mainland — overseen by Palestinian and multinational forces, with coordination with Israel. Security would be augmented by a “sea fence” and an outer layer of Israeli security.

Visual representation of the CNAS security plan

Visual representation of the CNAS security plan

Left: Visual representation of the CNAS security plan

Right: Visual representation of the CNAS security plan

Additionally, pursuant to a negotiated agreement, Israel could continue to exercise a number of options for protecting itself, by itself. Israel would still have its elite security apparatus operating at full capacity — including military, intelligence agencies, and police forces. Israel’s security barrier has been effective in helping to prevent terrorist infiltration but remains unfinished. Israel could complete the barrier to defend its new internationally-recognized borders.

However, the events of October 7th demonstrated that even a high-tech defense system is susceptible to relatively low-tech interference. For Israel to agree to such an agreement new systems, protocols, and defense capabilities would need to be implemented.

This would also likely entail the removal of Hamas from the Gaza Strip as many Israelis are convinced that their southern border remains vulnerable as long as the terrorist group remains in power. Hezbollah poses a similar, if not greater, threat along Israel’s northern border and many are closely watching the area to see if a full scale confrontation erupts. As of early 2024, Israel has signaled that a diplomatic agreement would be enough to avoid a direct conflict though it is possible that any agreement would only be a temporary solution.

What the Parties Gain from an Agreement

Both Parties

- Expanded security cooperation with upgraded internal and border security systems

- Enhanced regional political and security cooperation

- Long term U.S. and international aid and commitments

- End or reduction of the conflict and claims

Israel

- Right to defend itself, by itself, with U.S. support

- Gradual redeployment based on Palestinian performance

- Permanent West Bank security presence, through early-warning stations, remote monitoring and potential limited force in Jordan Valley

- IDF redeployed from outlying settlements to focus on national defense

Palestinians

- Recognition of Palestinian statehood and sovereignty

- Reduction of Israeli intrusions into Palestinian life

- Clear timetable for Israeli withdrawal

- Multiparty mechanism for resolving disputes to ensure adherence to timeline

DIGGING DEEPER

”Hamas’s October 7 Attack: Visualizing the Data” – Center for Strategic and International Studies

”Israeli Security After October 7” – Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Ariel Levite

”Two-State Security” Center for New American Security – Ilan Goldenberg

”An Alternative Gaza Strategy” Commanders for Israel’s Security – Amnon Reshef

”Enhancing West Bank Stability and Security” Commanders for Israel’s Security

“Security First” Commanders for Israel’s Security

“Israel’s Strategic Environment” Institute for National Security Studies – Amos Yadlin

“State with No Army, Army With No State” Washington Institute for Near East Policy – Neri Zilber

“Arab Peace Initiative” S. Daniel Abraham Center for Middle East Peace

*These materials are provided for reference purposes, with no intention of endorsement