Borders & Territory

The Israeli Security Barrier in the West Bank

Few issues are more central to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict—and efforts to resolve it—than the question of territory and where to draw a border as part of a negotiated agreement. For Palestinians, the 1967 lines are a critical baseline and are viewed as a historic compromise, whereas many Israelis view these lines as arbitrary boundaries that are not defensible.

Progress towards a resolution requires minimizing dislocations, ensuring security and establishing contiguous Palestinian territory. Of the many compromises required to reconcile each side’s requirements, land swaps have become a particularly important tool.

October 7th Update

October 7th marked the collapse of the policy of containment of Hamas in Gaza. For the last fifteen years, Israeli policy and practice had been to treat Gaza as being completely removed from the question of the West Bank. After October 7th and the ensuing war, the U.S. and its regional and Western allies have put the concept of a “pathway” to a Two-State Solution back into the conversation as a necessary political horizon to end the war. Secretary of State Antony Blinken on November 7, 2023 at the G7 laid out five principles regarding Gaza, “No use of Gaza as a platform for terrorism or other violent attacks. No reoccupation of Gaza after the conflict ends. No attempt to blockade or besiege Gaza. No reduction in the territory of Gaza. No forced displacement of civilians for Gaza”. Israel, though, seeks to retake control of the Philadelphi Corridor, the narrow strip of land on the Gaza side that marks the border between Egypt and Gaza in order to prevent smuggling and tunneling. Egypt objects as it does not want Israeli troops on its border.

Though no official plans have been published, there is much discussion within the Biden administration about a possible “grand bargain” that would entail Israel’s support for a political process that could lead to the creation of a demilitarized Palestinian state in exchange for normalized relations with Saudi Arabia. However, the Israeli governing coalition’s cabinet issued a “declaratory decision” rejecting any unilateral recognition of Palestinian statehood.

QUESTION

Can a border be drawn which establishes a Palestinian state roughly equivalent to 100% of the West Bank, Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem while including within Israel’s new borders the vast majority of Israelis living beyond the 1967 lines and ensuring security?

PALESTINIAN PERSPECTIVE

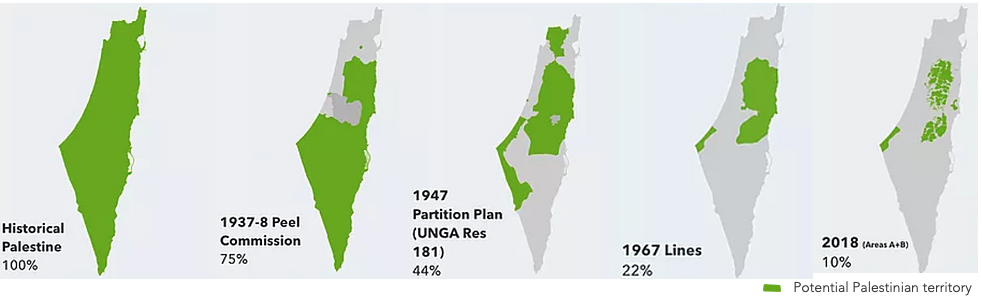

Many Palestinians see the entirety of the land between the Jordan River and Mediterranean Sea as their historic homeland, and believe they are entitled to 100 percent of it. But over time, Palestinians have seen their portion of the land recede — from 100 percent to 75 percent in 1937 (Peel Commission), to 44 percent in 1947 (United Nations Partition Plan), and finally to 22 percent in 1949 (Arab-Israeli War).

Today, Palestinians see their 22 percent shrinking, as Israeli settlements expand across the West Bank. The 1949 armistice lines served as Israel’s effective borders until 1967 — which is why they are known as the 1967 lines or Green Line. From 1949 – 1967, Jordan controlled the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and Egypt controlled the Gaza Strip, but Israel gained control of those areas in the 1967 war. Palestinians and much of the international community consider these areas to be under Israeli military occupation. In 1988, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) began to shift from its demand for 100 percent of the land to a state based on the 1967 lines — 22 percent of historic Palestine. Palestinians view this shift as their ‘historic compromise.’ Today, Palestinians see their 22 percent shrinking, as Israeli settlements expand across the West Bank.

Boiling down the Palestinian position:

A Palestinian state must comprise the equivalent of 100 percent of the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem — 100 percent of their 22 percent.

ISRAELI PERSPECTIVE

Many Israelis believe they have a historical and religious claim, dating back millennia, to all of the land between the Jordan River and Mediterranean Sea. This includes “Judea and Samaria,” the biblical name for the West Bank.

Map of Israel according to the Yesha Council

Many Israelis do not consider the 1967 lines as a basis for drawing borders, seeing them as arbitrary armistice lines that separated the Israeli and Arab troops in 1949. Additionally, many Israelis reject the characterization of the West Bank and East Jerusalem as “occupied” by Israel. Others argue that borders based on the 1967 lines are not defensible and ask, why should Israel return territory that it won in defensive wars?

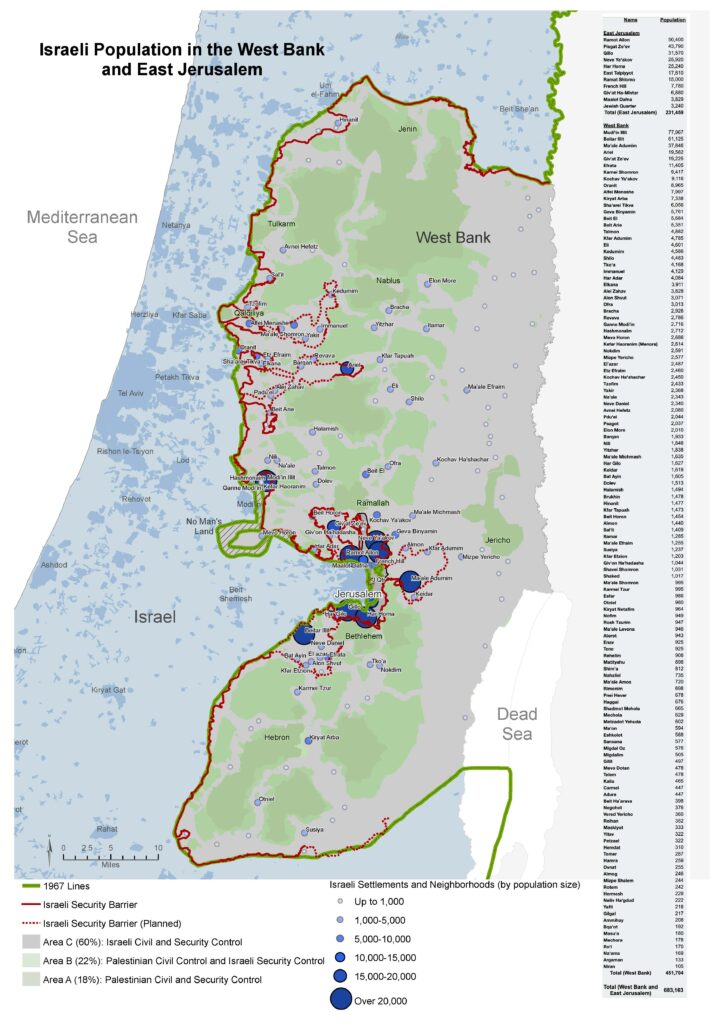

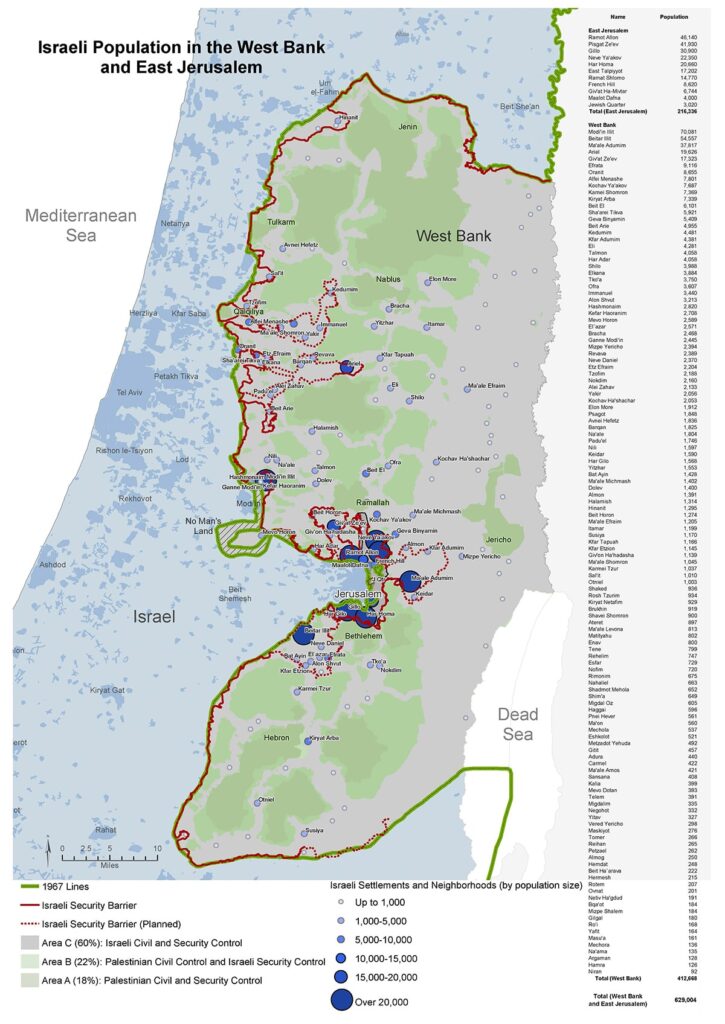

Primarily, the driving considerations for Israel on borders are security and demographic realities on the ground — specifically, Jewish neighborhoods in East Jerusalem, and Israeli settlements in the West Bank, that were built since Israel took control in 1967. In total, there are approximately (630,000+) Israelis who live beyond the 1967 lines–the vast majority in communities adjacent to the 1967 lines.

Often, Israelis do not distinguish between Israeli communities within the 1967 lines and those beyond them that are close by.

Boiling down the Israeli position:

Israel’s borders with a future state of Palestine must ensure security and include the vast majority of Israelis who live beyond the 1967 lines.

HELPFUL REALITIES

The map below illustrates that 75 percent of the 630,000 Israelis living beyond the 1967 lines — approximately 472,000 — reside close to the lines. According to a 2022 survey, this number may be as high as 85 percent who live within “an estimated 8% of the West Bank, largely adjacent to sovereign Israeli urban areas.” This means that minor modifications to the 1967 lines could incorporate the vast majority within Israel’s new borders while allowing for the emergence of a viable Palestinian state. Additionally, Israelis in the West Bank remain integrated with Israel and live lives largely separate from the Palestinians. For example, sixty percent of settlers work across the Green Line in Israel proper, and most Israeli youth attend school in Israel. The few hundred settlers who farm in the West Bank do so on only 1.5 percent of the land.

Israeli Population in the West Bank & East Jerusalem

CHALLENGES

Many experts argue that Israeli settlement growth in the West Bank poses a threat to a two-state agreement. Expansion of settlements — especially those further from the 1967 lines — increases the number of Israelis who would likely find themselves outside the territory annexed to Israel in an agreement. These Israelis may need to be relocated from settlements deeper in the West Bank, although some have also suggested they could be incorporated into the Palestinian state as Israeli citizens with Palestinian residency. As outlying communities continue to grow, there may come a point — some argue soon — when relocation is no longer politically feasible. Notably, the Israeli government has voiced opposition to evacuation.

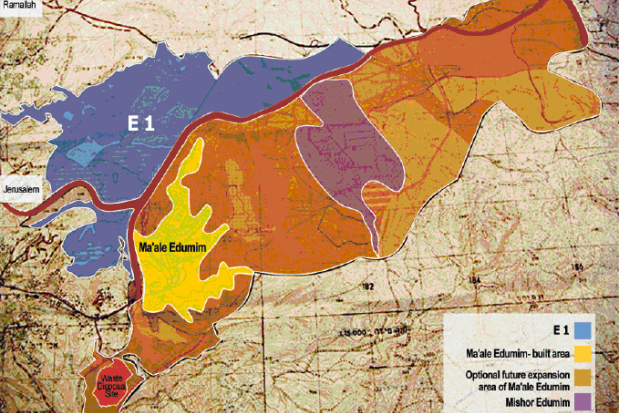

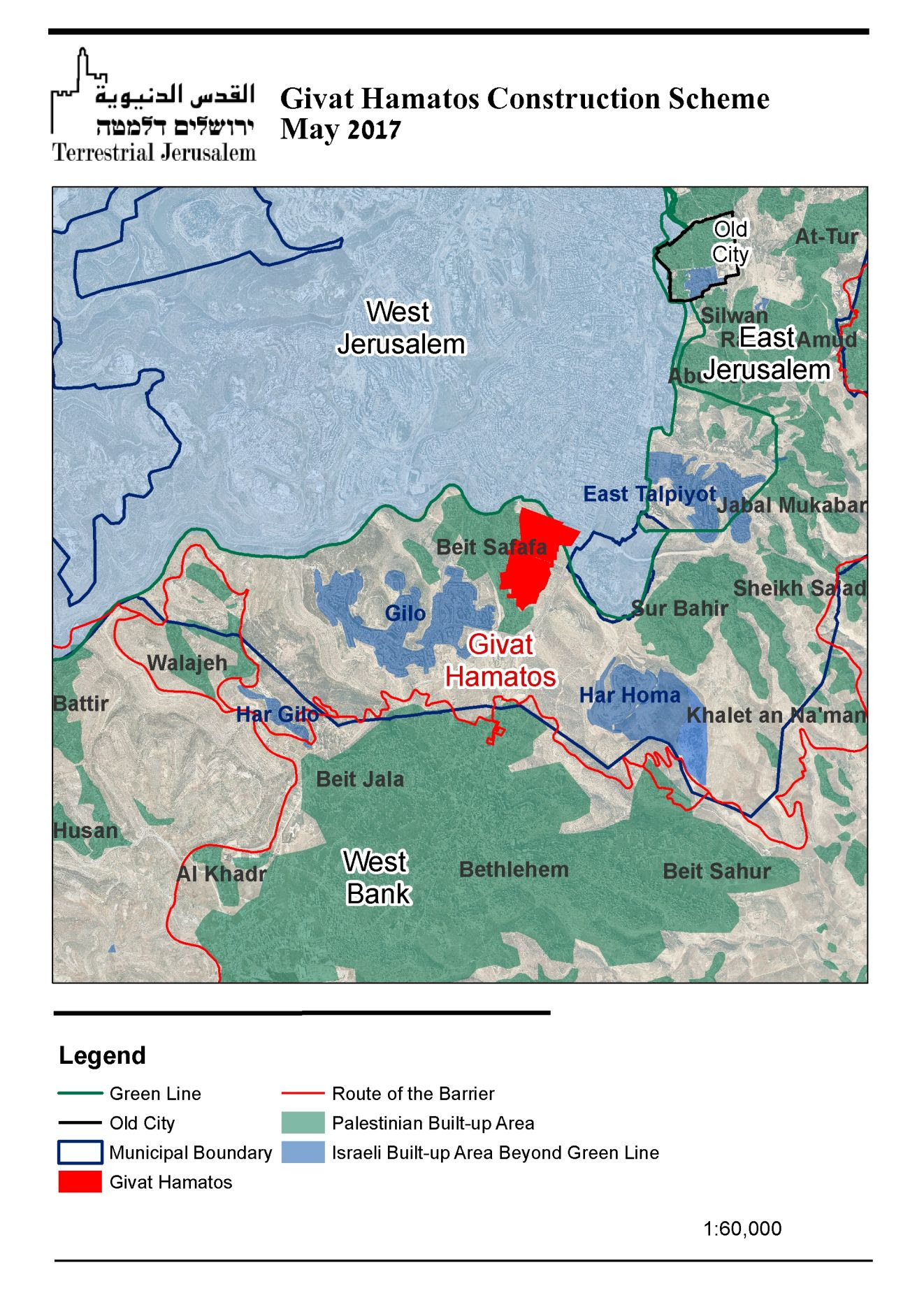

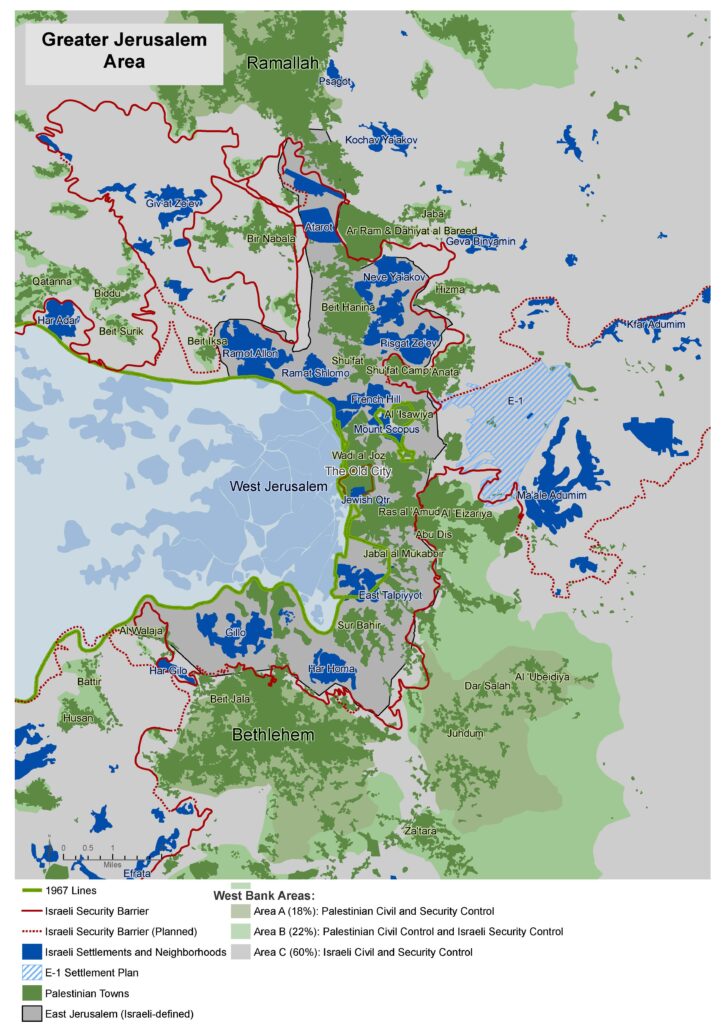

Further expanding Jewish neighborhoods in and around East Jerusalem could also significantly complicate a two-state agreement. By cutting off Palestinian areas in the West Bank from Palestinian East Jerusalem and dividing the West Bank into northern and southern sectors, settlement projects like E1 and Givat Hamatos could prevent a viable and contiguous Palestinian state.

Expanding Jewish neighborhoods in these areas has mixed support in Israel’s current governing coalition. In June 2023, PM Netanyahu postponed a contentious meeting on the development of E1. However, in December 2023, around 1700 housing units were approved just north of Har Homa making it “the first major neighborhood in East Jerusalem to be approved since 2012.”

Greater Jerusalem Area

In response to the second Intifada (uprising), as scores of Palestinian suicide bombers entered Israel largely unchecked, Israel embarked on building a physical barrier — a fence complex in open areas, and a concrete wall in urban areas — that separates Israeli population centers from the vast majority of Palestinians in the West Bank.

The Israeli Security Barrier (Ahmad Gharabli/AFP)

The barrier’s security effectiveness is proven, but its trajectory remains a point of contention. In some cases, it separates Palestinians from lands they own and cultivate, and, notably, it divides parts of East Jerusalem from the West Bank. If the barrier were completed, it would leave roughly 8 percent of the West Bank on the Israeli side. The below map illustrates the route of the security barrier.

Route of the Israeli security barrier

Possibly the biggest challenge is the threat of Israel annexing significant portions of the West Bank. Except in Jerusalem and the Golan Heights, Israel has refrained from taking measures that would suggest it has formally annexed the West Bank. Until the Trump administration, annexation was long considered a red line by the U.S. and the international community, and most Israelis understood that such a move might compromise the country’s Jewish and democratic character, given the large Palestinian population that annexation might place inside of an expanded Israel.

In a groundbreaking op-ed in an Israeli newspaper in June 2020, UAE Ambassador to the U.S., Yousef al-Otaiba warned Israel against unilaterally annexing portions of the West Bank. Israel agreed to refrain from annexation and the UAE-Israel normalization agreement, known as the Abraham Accords Peace Agreement, was concluded shortly thereafter.

Annexation proposals have ranged from modest plans to annex only sections of close-by settlement blocs to more ambitious plans to annex all of Area C of the West Bank including the Jordan Valley.

NARROWING THE CONFLICT

For two decades, both sides have presented various proposals for land swaps, including some based on leasing territory–and the U.S. has put forward its own proposals to try to bridge remaining differences.

The below two maps reflect the proposals made by Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert and Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas in peace talks in 2008 that were sponsored by the George W. Bush Administration.

Israeli borders proposal (Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, 2008)

Palestinian borders proposal (Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, 2008)

Left: Israeli borders proposal (Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, 2008)

Right: Palestinian borders proposal (Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, 2008)

In these negotiations between Abbas and Olmert, the bulk of the disagreements focused on the Ariel bloc in the north, and the Jerusalem envelope in the center. Ariel is important to Israel because of its sizable population (19,000+). However, Israeli annexation of Ariel would violate Palestinian requirements — Ariel is not adjacent to the 1967 lines, and its annexation would impede Palestinian contiguity. Ariel illustrates the challenge involved in reconciling Israeli demographic concerns and Palestinian demands for a viable and contiguous state.

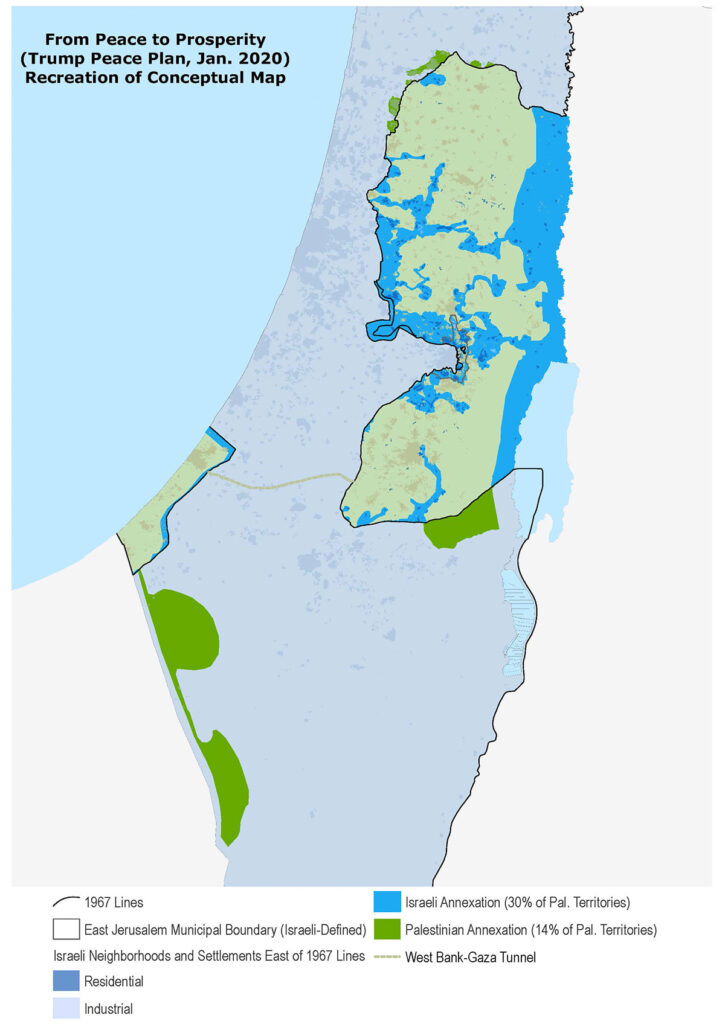

In January 2020, President Donald Trump presented the “From Peace to Prosperity” plan which contained the below map which was the first map presented by the United States, which previously had made proposals based on percentages and other elements of a solution. Among its many objectives, the Trump plan provides that no Israeli or Palestinian will be relocated. Thus, 15 Israeli settlements would remain in the new Palestinian state and 54 Palestinian towns would become enclaves in West Bank areas annexed by Israel.

As well, in 2019, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo reversed the State Department’s legal position, held since 1978, that civilian Israeli settlements in the West Bank were “inconsistent with international law.” However, in 2024, Secretary of State Antony Blinken again reversed the Trump administration’s decision and returned to the previously held policy.

Trump’s “From Peace to Prosperity” plan (2020)

In between official rounds of negotiations, many Israeli, Palestinian and American former officials and experts have devised various proposals outlining borders between Israel and a new Palestinian state. Here are some examples:

- 2003 Geneva Initiative

- 2010 Baker Institute Report

- 2011 Makovsky Report

- The Strange Resurrection of the Two-State Solution – Foreign Affairs Martin Indyk

Digging Deeper

”Human Perspective of Palestinian Movement” Video

”The West Bank Security Barrier and Its Gaps” I24 News – Simcha Pasko

“Givat Hamatos and Mordot Gilo in Context” Terrestrial Jerusalem

”Ramifications of West Bank Annexation: Security And Beyond” Commanders for Israel’s Security

”Enhancing West Bank Stability and Security” Commanders for Israel’s Security

”Regulating Israeli and Palestinian Construction in Area C” Commanders for Israel’s Security

*These materials are provided for reference purposes, with no intention of endorsement.