Economics & Trade

October 7th Update

Over one-third of the Palestinian GDP traditionally has been made up of Palestinian laborers working within Israel. Considering that some Gazan workers have been accused of using their work permits to gain intelligence on Israeli areas that were targeted in the Hamas attack, there is little to no appetite in Israel for Palestinian laborers to return as before. October 7th marks a further disintegration of the Israeli and Palestinian economies and highlights the need for localized investments within the Palestinian private sector to compensate for the major reduction in Palestinian GDP. Israel is planning to add over 50,000 foreign workers from friendly countries in the Far East and elsewhere to replace Palestinian workers. In an attempt to further disintegrate the Israeli and Gaza economies, Israeli Foreign Minister Yisrael Katz has called for an artificial island off the coast of Gaza to become the hub for trade and humanitarian assistance after the war to provide a secure way for the territory to be connected to the world.

During the current war, as Israel increasingly comes under pressure to distribute adequate humanitarian assistance a variety of secondary options have developed. These include US airdrops of Jordanian supplies and a land route transporting Moroccan supplies via Kerem Shalom. In March 2024, the US and other countries built a pier off the coast of Gaza to increase the influx of humanitarian aid via Cyprus.

Another major development has been Houthi attacks on ships coming through the Red Sea in response to the Israel-Hamas war. Trade through the Red Sea has long been a major chokepoint and area for potential disruption though the tension has increased in recent months. The Houthis announced they would attack all ships bound for Israeli ports until more humanitarian aid is brought to Gazans. Since mid-October, there have been at least sixty Houthi attacks on ships coming through the Red Sea and several ships associated with Israeli businesses have been seized (although most do not have any connection with Israel or the US). This has forced many ships to take longer alternative routes around South Africa. In response, the US and UK launched airstrikes on Houthi areas in Yemen. Though the effects to date are limited, the Houthis and their backers in Iran can play a disruptive role in international trade.

BACKGROUND

The Israeli and Palestinian economies remain deeply intertwined. Electricity, water, labor markets, food supply, consumer goods and numerous other sectors bind the two economies, even as the Israeli and Palestinian people remain effectively separated from one another. Israel’s currency, the shekel, remains a primary currency for the Palestinian economy, and the two economies remain bound by a customs and import tax union negotiated during the Oslo peace process in the 1990s.

100 (NIS) New Israeli Shekels (Nati Shohat/Flash 90, 2017)

Israel remains the Palestinians’ largest trade partner and primary export market.1 See Bader Rock and Yitzhak Gal, Tony Blair Institute for Global Development, London, 2018, https://institute.global/sites/default/files/articles/Israeli-Palestinian-Trade-In-Depth-Analysis.pdf More than 120,000 Palestinians work in Israel daily, and large numbers of Israeli Arabs travel regularly to the West Bank for commerce and higher education—opportunities often facilitated by the U.S. government and American civil society.

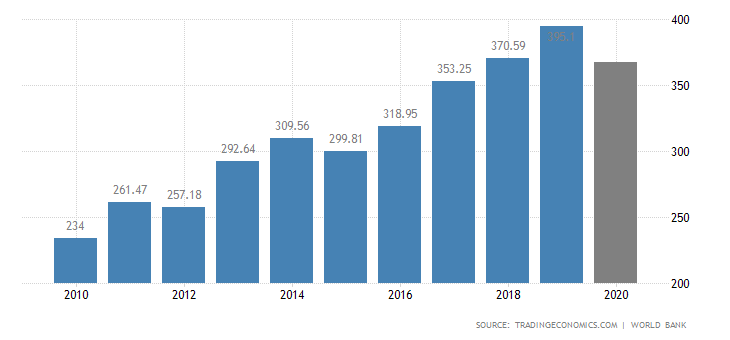

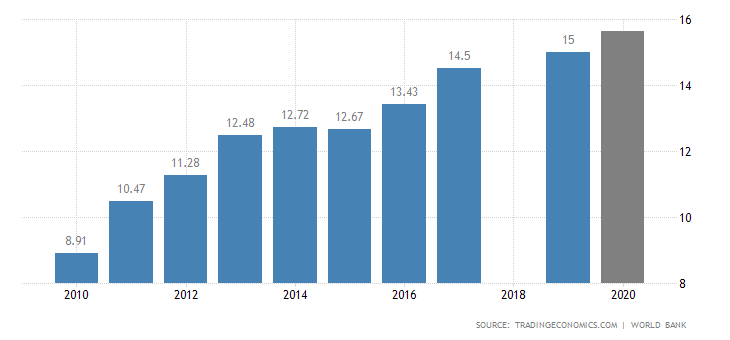

It is important to remember that the two economies are vastly unequal. Israel is an economic behemoth, with few lingering effects of the crippling Arab boycott of decades past, and a much more manageable defense budget due to the dividends from the peace treaties with Jordan and Egypt and the nearly $4 billion in annual U.S. defense assistance. Israel’s GDP is over $350 billion, while the Palestinian economy is closer to $15 billion.2 World Bank figures.

The accrued effects of decades of varied levels of Israeli military control and repeated cycles of conflict have left the Palestinian economy severely impacted, although it does boast a highly educated populace and additional human capital and investment potential via the Palestinian diaspora.

Israel’s separation barrier with the West Bank, its security barriers with Gaza and its ongoing security cooperation with the Palestinian Authority—supported by the U.S.—provide Israel with the security and confidence to consider further economic measures that could provide a boon for all sides. Although Palestinians have ended security cooperation at moments of particular stress and tensions in the relationship, cooperation currently continues.

Many aspects of economic development and cooperation depend on improved Palestinian movement and access, which remains constrained by Israeli restrictions. Many of Israel’s security authorities, however, believe improved Palestinian movement and access can be achieved without compromising the safety of Israelis.3 See “INSS Plan,” authored by a number of Israel’s leading security authorities, including Generals Amos Yadlin and Udi Dekel, Israel Institute for National Security Studies, 2018, https://www.inss.org.il/inss-plan-political-security-framework-israeli-palestinian-arena/; see also Commanders for Israel’s Security, Security First: Change the Rules of the Game, 2019, http://en.cis.org.il/wpcontent/uploads/2016/05/snpl_plan_eng.pdf Security officials are acutely aware of the fundamental connections between economic stability and security, and they also understand that broader economic equities are at stake, including environmental protection, public health and countering violent extremism.

ECONOMIC Links & Anti-Normalization

Even though Israel is the largest trade partner for Palestinians, when economic links between Israeli and Palestinian companies are spotlighted, Forbes4, often there can be a Palestinian backlash. While building the economy of the Palestinian Territories is an essential step to a sustainable political solution, Palestinians have been cautious of those who preach the concept of an ‘economic peace’ at the expense of a political one. Palestinians point to the recent past where they have been offered economic incentives instead of a political horizon leading to a state of their own. Given this dynamic, the Trump administration stressed that there could be no economic investment without an agreement on the wider political situation.

Forbes cover profits for peace (2013)

Economy & Settlements

In recent years, and encouraged by the Trump administration, there has been a push by some in the settlement community, to develop economic partnerships and ties with the local Palestinian community. For some settlers this effort is divorced from any sense of politics and looks to ‘normalize’ settlements into the fabric of the rest of the regional economy and be a driver of non-political peaceful relationships with the local population. The settler business owners point to industrial parks and joint businesses as places to promote Palestinian entrepreneurship and enhance wages for Palestinian workers. These types of Israeli commercial initiatives are tied to the desire to normalize settlements in the wider discourse as a part of the solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, rather than a problem to be overcome by a peace process. The move to create economic relationships with the local settler population is seen as deeply unacceptable by the Palestinian political class. In addition, much of the international community sees these efforts as a way to gloss over the violation of international law that holds settlements as illegal.

Spotlight on Rawabi

Waiting for political progress has frustrated many leading Palestinian entrepreneurs and business leaders. Wanting to take control of what a new state of Palestine could look like, Palestinian developers’ broke ground on the city of Rawabi in January 2010. The new city near Ramallah has faced many obstacles, from Israeli permits to local opposition. Despite this, more than 3,000 Palestinians have taken up residence in the modern new city which serves as a technology hub for the Palestinian economy and offers promise for Palestinians.