For decades, international political actors – such as diplomats and heads of state – have sought to mediate the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in an attempt to resolve, or at least manage it. In parallel to these official actors, there is another category of mediators which can be referred to as “insider mediators.” In the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, insider religious mediators are religious leaders who attempt to advance a warm ‘religious peace’ and mitigate crisis situations as they arise.

International Political Mediation

U.S. mediation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict grew out of American mediation of Israeli-Arab agreements. It was shaped by a state-centered paradigm which was conceived to generate diplomatic agreement between governments. The role of mediation was seen as consisting of five tasks: (1) establishing contact when the parties cannot afford to declare it at the beginning of the process, (2) exploring positions to determine the existing amount of convergence and set an attainable target, (3) providing necessary persuasion, pressure and incentives, (4) suggesting bridging solutions, and (5) providing credible guarantees for implementation.1 Ezzedine Choukri-Fishere, Against Conventional Wisdom: Mediating the Arab-Israeli Conflict, Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, 2008.

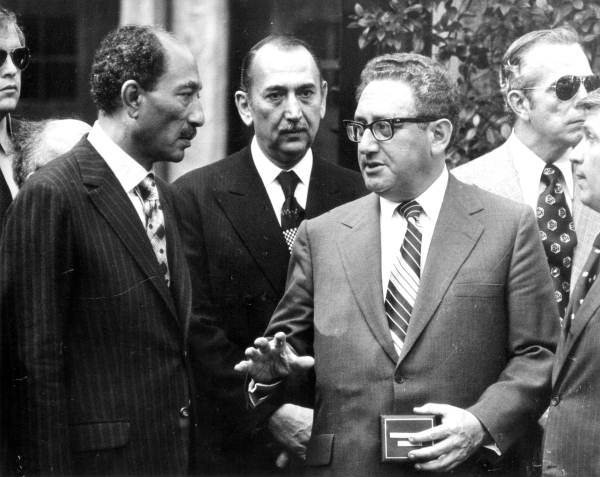

The agreements consolidated the cessation of hostilities and laid the ground for future peace talks. High-level U.S. mediation was critical for success. At first, after the 1973 Yom Kippur War, through U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s shuttle diplomacy, the U.S. mediated both Israeli-Egyptian and Israeli-Syrian disengagement agreements. The agreements consolidated the cessation of hostilities and laid the ground for future peace talks. After failing to convene direct negotiations between Israel and all its Arab neighbors through an international conference, a breakthrough was achieved in bilateral Israeli-Egyptian negotiations, which enjoyed a boost from Egyptian President Anwar Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem.

However, only after 13 days of active mediation by U.S. President Jimmy Carter at Camp David did President Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin sign the Camp David Accords (1978). And the following year it was only after President Carter shuttled for two weeks between Cairo and Jerusalem did the parties reach the Israeli-Egyptian Peace Treaty (1979).

Egyptian President Anwar Sadat (left) and U.S. National Security Adviser and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (right) (Wikimedia, 1973)

However, U.S. mediators underestimated the considerable criticism these agreements would encounter regionally, in Egypt and Israel. Egypt’s regional standing took a major blow and it was consequently expelled from the Arab League, and the Egyptian public evinced great difficulty in accepting recognition of Israel. In Israel, Gush Emunim, the pro-settler religious Zionist movement led by Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook, opposed the agreement, both because it included the evacuation of Israeli settlements from Sinai and approved of Palestinian autonomy on lands Judaism deems divinely promised to the Jewish people. Nevertheless, the very success signaled by the signing of these agreements, as the most powerful Arab country and Israel ended the state of warfare between them, created in Washington D.C. a sense that high-level U.S. brokering of bilateral negotiations is the most efficacious peacemaking route.

Seeking to build on these successes and mediate Israeli-Palestinian agreements, the U.S. first had to also establish relations with the Palestinian side. Though the Camp David Accord included a commitment to establish an elected Palestinian self-governing authority, Israel initially refused to engage with the PLO and the U.S. refused to do so without Israel’s approval. Many mediation efforts, including by European states, focused on creating dialogue between the U.S. and the PLO. In 1988, the U.S. accepted that the PLO met three conditions – recognizing Israel’s right to exist, accepting UN Resolution 242 and renouncing terrorism – and the two entered political dialogue.

New York Times front page December 15, 1988

This political dialogue allowed the U.S. to cooperate with Russia and convene in 1991 in Madrid a comprehensive peace conference, involving all relevant Arab countries. Due to Israel’s rejection of the PLO, a non-PLO Palestinian delegation attended as part of the Jordanian one. In the Madrid Conference all the attending countries formally accepted UN Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338 as a basis for future agreements, laying a foundation for territorial partition as the guiding principle with respect to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

With Israel considering the PLO a terrorist organization, high-profile U.S. attempts failed to capitalize on the newfound relationship with the PLO. Norway discreetly opened a secret communication channel between Israel and the PLO, which guided the parties toward crafting a declaration of principles which would serve as a basis for future peace agreements and provide bridging proposals to support the talks. When the parties reached agreement in 1993, Norway handed the process to the U.S. so that it would use its greater resources to chaperon it further. The Declaration of Principles’ signing ceremony took place in the U.S.. This progress on the Israeli-Palestinian track opened the door for the U.S. to support Israeli-Jordanian negotiations, which concluded in 1994 with the signing of a peace agreement between the two countries.

The U.S. subsequently brokered a series of Israeli-Palestinian agreements between 1994 and 1999, leading to Palestinian self-rule with the establishment of the Palestinian Authority and the launching of a five-year process consisting of a gradual expansion of the areas in which it operated. Egypt and Jordan acted as supporting mediators throughout these years, helping the U.S. secure consent from both Israel and the PLO on a large variety of issues. The outcomes were, however, a mixed bag. Many in both societies strongly opposed the agreements. In particular, Hamas and other Palestinian factions perpetrated violent attacks against Israelis. And religious Zionists ratcheted up their settlement construction efforts in order to prevent partition and limit the scope of concessions the Israeli government could offer.

U.S. mediation failed to offer remedy to the opposition of these mostly non-liberal religious constituencies.2 Ofer Zalzberg, Beyond Liberal Peacemaking: Lessons from Israeli-Palestinian Diplomatic Peacemaking, Review of Middle East Studies, Issue 53, Volume 1, 2019.U.S. administrations tended to consider these groups “irrational” and “fundamentalist”, posting they, therefore, can only be defeated, revealing the administration’s’ own statist and liberal biases. The statist bias was manifested in the U.S. mediator’s engagement primarily only with governments. The interests and values of communities and groups which were not represented by these governments were ignored.

Because for the most part the Israeli and Palestinian governments at the time had a mostly materialistic and secular approach, this exclusion was arguably most pronounced with respect to two kinds of constituencies: those committed to the so-called identity-related core issues of the conflict since 1948 (e.g. Israel’s Jewish character, the status of Israel’s Arab-Palestinian minority and refugee rights) and non-liberal national-religious populations (notably non-liberal religious Zionists and Hamas). The U.S. mediator’s secular, liberal bias, shared to an extent by that of the Israeli Labor Party and the Palestinian Fatah party which were in power for much of the 1990s, was evinced in the basic premises of the U.S. brokered interim agreements. The agreements assumed a correlation between the advancement of human rights, free markets, liberal democracy and international law, on the one hand, and, on the other, the promotion of peace. The 1990s were the heyday of liberal peacemaking, and U.S. policies were promoted, sometimes unconsciously, based on a sense that liberalism has won the day and should be promoted along with peace. However, many ultra-Orthodox Jews and religious Zionists, as well as so called Palestinian “Islamists,” have perceived the Oslo process since the 1990s as an attempt to advance international law at the expense of their respective religious laws, the Halacha and the Sharia. Similarly, the liberal utopia of a conflict-ending distributive compromise, clashed with religious visions and eschatologies which maintained that the land is sacred and therefore indivisible. Indeed, among the major reasons for the failure of these agreements to win broad, durable support in both societies was the omission of the land’s sanctity in the eyes of to large parts of both societies.

Apprehensive of the growing opposition to the peace process, mindful of the original five-year deadline and keen to win over adversaries of the process by disproving their claims of intractability, U.S. mediation shifted in the year 2000 toward attempting to broker a comprehensive, conflict-ending Israeli- Palestinian peace agreement. The U.S. mediators helped Israel and the PLO learn of each other’s positions on the so-called hardest issues of discord and ultimately President Clinton offered bridging proposals for addressing each of them in a conflict-ending agreement: borders, security, settlements, refugees and Jerusalem. The talks failed to give birth to an agreement. Worse, disappointment from the failure and acerbic mutual accusations for it provided the breeding ground for a major escalation, known as the Second Intifada.

International attempts to curb the mounting violence erupting from the Second Intifada (2000) signaled a shift from conflict resolution to conflict management and from exclusive U.S. mediation to a U.S.-led coalition of international mediators. In order to end the violence, the U.S., the European Union, the United Nations and Russia formed the International Quartet. Their jointly proposed violence mitigation efforts were codified as the first of three phases of the “Performance-Based Roadmap to a Permanent Two-State Solution to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict”. The second, transitory phase included an optional agreement between Israel and a Palestinian state with provisional borders a third phase called for a permanent status agreement. The process failed to complete even its first phase and the Second Intifada lasted until 2005.

From the perspective of mediation, one lasting outcome of the process has been the United States Security Coordinator for Israel and the Palestinian Authority (USSC), established with the stated aim of meeting U.S. commitments under the Roadmap.3 The USSC coordinates with the Government of Israel and the Palestinian Authority to enhance security cooperation; leads coalition efforts in advising the Palestinian Authority on security sector reform; and recommends opportunities for nations and international organizations to contribute to the development of a self- sustaining Palestinian security sector.The USSC effectively fosters Israeli-Palestinian security coordination brokering understandings between the security apparatuses of both parties. In addition, the position of a Quartet Envoy was established, creating a point-person who could mediate as a representative of the members of the International Quartet between Israel and the PLO. The envoy’s initial focus was Israel’s Gaza disengagement but it later grew to broader conflict management and conflict resolution. With the years, the Quartet established a robust Office, conducting low-level mediation between the parties.4 OQR Office, as part of its objective to “support the Palestinian people to build the institutions and economy of a viable, peaceful state in Gaza and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem”, coordinates between Israel and the PA regarding Energy, Water, Rule of Law, Movement & Trade, Telecommunication and Economic Mapping.

The Quartet – UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton, and High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy of the European Union Catherine Ashton – met in Moscow. They were joined by Quartet Representative Tony Blair (The Quartet, 2010)

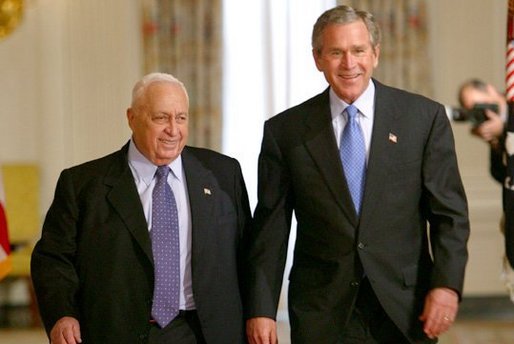

Given the sense of Israeli-Palestinian intractability, the U.S. shifted to coordinating with Israel unilateral acts which it deemed aligned with a two-state vision. With President George W. Bush’s blessing, Israel unilaterally withdrew all its settlements from the Gaza Strip and from a small area in the north of the West Bank. The U.S.-Israeli decision to advance such a step without coordination with the Palestinian leadership, allowed Hamas to convincingly claim among Palestinians that it was its military actions which forced Israel’s withdrawal and that its violent strategy can more effectively promote Palestinian liberation. This boosted Hamas’ popularity, contributing to its victory over Fatah in Palestinian parliamentary elections in 2006.

President George W. Bush and Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon at the White House (White House Archives, 2004)

Once Hamas got to power in Gaza through a military coup in June 2007, mediators faced a need to coordinate with a new governmental entity. Most western governments were unable to do so because of Hamas’ listing as a terrorist organization. Two western countries, Switzerland and Norway, did enter the role of third-party mediation, shuttling discreetly between Gaza, Jerusalem and Ramallah on a variety of issues. The Office of the United Nations Special Coordinator (UNSCO) initially played a similar liaison role regarding Gaza, which expanded to mediating ceasefires, humanitarian aid and stabilization, particularly in recent years. Egypt, the Gaza Strip’s southern neighbor, also found itself in the role of a mediator between Israel and Hamas.

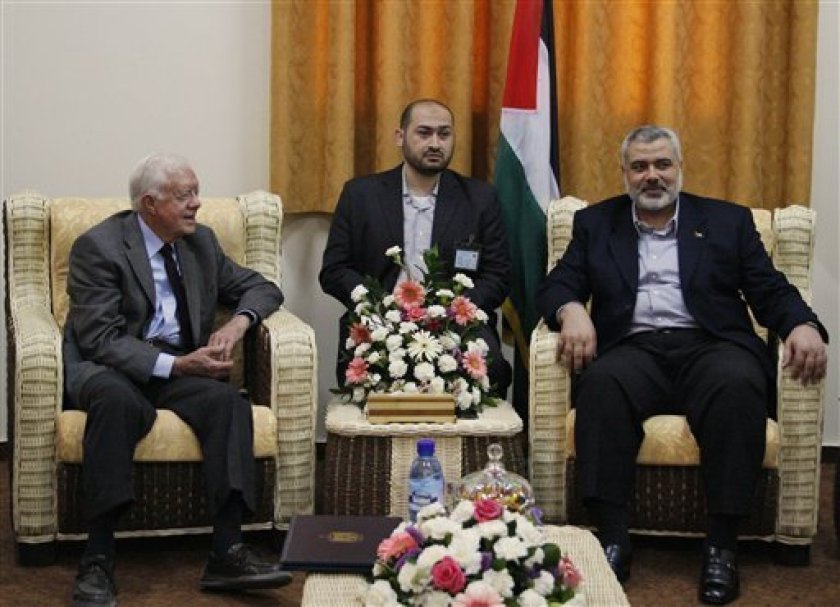

However, being an interested party, and having direct control over Gaza’s southern border and adjacent maritime areas, Egypt has been a different kind of mediator – one which both enjoys more levers over the parties and yet is also susceptible to pressure from them. With the exception of the period in which Egyptian President Mohammad Morsi (a member of the the Muslim Brotherhood) in Cairo, Egypt engaged with Hamas solely through its intelligence service, in order to avoid granting it legitimacy in the process. Two former heads of state, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and former U.K. Prime Minister Tony Blair, have taken advantage of the greater maneuvering room which non-governmental mediation allows in order to engage with Hamas’ leadership toward the broader aim of conflict resolution. They met regularly, directly and indirectly, with Hamas leaders, exploring among other things what context and understandings would be necessary for Hamas to abide by the outcome of Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, or even take part in them. These and other non-governmental mediation efforts have been ongoing since, but government-led mediation to date failed to effectively leverage them.

Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter sits with Ismail Haniyeh, head of Gaza’s Hamas government, during their meeting in Gaza City (Ashraf Amra/AP Photo, 2009)

U.S. mediation shifted back to pursuing conflict resolution, starting with the Annapolis Process (2007-2008), in which Israel and the PLO tried again to strike an end-of-claims agreement. After the bloody and ruinous years of the Second Intifada, the political context was extremely negative, and the odds of diplomatic success seemed so low. Moreover, the division of the Palestinian arena between the PA-ruled West Bank and the Hamas-ruled Gaza, led the U.S. mediator to support the quest for a “shelf-agreement”, i.e. one which would be signed and then shelved until conditions allowed its implementation. Consequently, opposition efforts were less sizable and palpable than those of the 1990s.

The Annapolis Summit (2007-2008)

However, Annapolis failed to conclude an agreement. Mediators then shifted their aim to merely reaching accord on broad-stroke principles. Efforts by U.S. Envoy George Mitchell (2009-2011) and Secretary of State John Kerry (2013-2014) were different in seeking to elicit agreement only on core principles (an “agreed-upon frame of reference”) rather than a fully negotiated treaty, but similar both paradigmatically and in terms of their outcome: failing to achieve consent around the core conflict issues, let alone from non-liberal religious constituencies.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (first from left), U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (second from left), Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas (third from left), and U.S. Special Envoy for Middle East Peace George C. Mitchell (fourth from left) chat after their meeting in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt (State Department photo, 2010)

In the face of persistent intractability, mediators increasingly employed coercive diplomacy in order to compel one of the parties to accept specific parameters for resolution. The Obama Administration allowed the passing of UN Security Council Resolution 2334 in order to reaffirm and consolidate a legal international consensus regarding the 1967 lines as the basis for the borders between Israel and the future state of Palestine. The resolution sought to exact a cost for Israeli settlement construction by calling upon all states “to distinguish, in their relevant dealings, between the territory of the State of Israel and the territories occupied since 1967”. For the Israeli Right, most considered this resolution to be negating Jewish attachments to Judea and Samaria.

After the United States chose to abstain from the vote, the United Nations Security Council passed resolution 2334 (Jane Lane/European Lane, 2016)

The Trump administration increased diplomatic coercion, but directed it at Palestinians. Economically, the Trump administration employed both carrots and sticks: it both ended direct U.S. support to Palestinians (through USAID and UNRWA) and, at the Bahrain Conference, offered a major financial package in favor of the Palestinians to support the Trump ‘Peace to Prosperity’ Plan. Substantively, the Trump administration established U.S. positions in a manner favoring Israeli policies, notably by recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and taking the position that Israeli settlements are not illegal according to international law.

The Trump administration also presented a detailed peace plan advocating a “realistic two-state solution”, offering Palestinians far less than had been the international consensus until then and much less than the PLO declared to be its minimum positions. The entire set of moves was vehemently rejected by Palestinians, both from the PLO and Hamas, who deemed the U.S. positions a fundamental transgression of both Palestinian nationalism, which accords paramount status to Jerusalem and the al-Aqsa Mosque, and Islamic jurisprudence, which in some interpretations precludes permanent partition of the land. Tellingly, Torani Religious Zionist Israelis similarly rejected the Trump Plan, despite its obvious favoring of Israeli interests over Palestinian ones, on account of its approval of permanent territorial partition which their interpretation of Judaism prohibits.

Palestinians holding flags of Palestine, march to protest against the Trump peace plan on (Mostafa Alkharouf/Anadolu Agency, 2020)

‘INSIDER RELIGIOUS MEDIATORS’ ADVANCING RELIGIOUS PEACE IN THE CONTEXT OF THE ISRAELI–PALESTINIAN CONFLICT

(by Daniel Roth)

Introduction:

For decades, international political actors – such as diplomats and heads of state – have sought, often with little success, to mediate the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in an attempt to resolve or at least manage it. Yet, parallel to these international efforts, there is another, often overlooked, power structure that nonetheless wields significant clout within the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and can be referred to as ‘insider religious mediation.’ Insider religious mediators are well-connected members of religious communities, often religious leaders, who attempt to advance a ‘warm’ peace and mitigate crisis situations as they arise. This article will explore the questions: What does insider religious mediation in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict look like in practice? How does it work? Who are the religious leaders who have been serving in this capacity? And what are some of the key milestones and case studies of this often overlooked, behind-the-scenes religious peace process?

What is ‘Insider Religious Mediation’?

The United Nations Development Programme defines an insider mediator as “an individual or group of individuals who derive their legitimacy, credibility, and influence from a socio-cultural and/or religious – and indeed, personal – closeness to the parties of the conflict, endowing them with strong bonds of trust that help foster the necessary attitudinal changes amongst key protagonists which, over time, prevent conflict and contribute to sustaining peace.”5 Cited in United Nations Development Programme. Engaging with Insider Mediators – Sustaining peace in an age of turbulence, 27 Apr. 2020, p. 7.

In their 2016 report “Support to Insider Mediation,” the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) notes that insider mediators, as opposed to outsider mediators, “may be rooted in resources from the local culture and also from religion” and are often, therefore, religious leaders or authorities, that their “legitimacy and effectiveness to mediate is not necessarily based on impartiality but on partiality and closeness to the context,” and, finally, that their “crucial advantage” is their “closeness or access to some of the conflict parties that no one else can reach out to, especially radical, hard-to-reach and armed actors.”6 Mubashir, M., E. Morina, and L. Vimalarajah. “OSCE Support to Insider Mediation: Strengthening mediation capacities, networking, and complementarity,” Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe, 2016, p. 28.

Insider Religious Mediation in the Context of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

Insider religious mediation does not mean advancing people-to-people grassroots religious peacebuilding programs or even necessarily engaging religious leaders in facilitated dialogue groups (though they may give their support to these important activities). Rather, it functions as a channel of mediation alongside the formal governmental mediation process, working to connect the very stakeholders whose worldviews have traditionally collided and who have rejected the various political peace processes. They do not seek to replace the formal political process, however. Rather, they help ensure religion no longer serves as a barrier to peace7 See Bar-Siman-Tov, Yaacov, editor. “Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies – Study no. 406: Barriers to Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, 2010.but instead as a critical bridge to a ‘warm’ peace, meaning a peace between religious leaders and their communities who see each other as neighbors and partners and not enemies. This model of mediation is in line with traditional religious models of third-party mediation and deviates strongly from modern Western forms of professional mediation.8 For more on the difference between traditional and religious models of mediation versus modern Western models, see Roth, Daniel. Third-Party Peacemakers in Judaism: Text, Theory, and Practice, Oxford University Press, 2021, pp. 21-36.

Insider religious mediators seek to engage more senior and often more extreme religious and political leaders or stakeholders who have significant influence over worldviews that have come into conflict. Through an ever-expanding network of deeply trusted relationships, they arrange discreet and intimate meetings with these stakeholders. These meetings may take place in Israel, the Palestinian territories, or abroad, such as in Istanbul, Athens, Oslo, etc.

They always address the political reality at hand, whether it be a change in the current political climate, a particular crisis situation, or an opportunity to introduce a new leader into their intimate network of relationships. Meetings can range from just a few people to as many as fifteen or twenty, each participant simultaneously serving as a religious leader and potentially as an insider mediator.

For example, a meeting may take place between an Islamic-Palestinian insider mediator and a more senior Islamic leader. They may discuss, among other topics, the possibility of introducing the senior Islamic leader to other trusted partners within the insider mediator network, such as a Jewish-Israeli insider mediator, who is himself a representative religious leader of the ‘other side.’ The more senior that the leader being approached is, the more likely several other insider religious mediators will attend the meeting, each one bringing to the room their own reputation and connections. These insider religious mediators often do not see themselves and certainly do not introduce themselves as ‘mediators,’ but rather as religious leaders. Usually, it is the more junior religious leader who actively wears the label of ‘mediator,’ going back and forth between superiors to help weave together the network of relationships.

What is ‘religious peace’?

Religious peace is a warm peace. It is often contrasted with secular or political peace. Political peace may be understood as consisting of a peace agreement negotiated and signed by (primarily) secular politicians, often with a liberal worldview, and based on tangible interests (i.e., economics, demographics, security, natural resources, etc.). In contrast, religious peace is achieved on a foundation of shared core religious values and beliefs—for example, the belief, as articulated by Rabbi Michael Melchior, that “we are all created by and in the image of the same God” and “that crushing the other is crushing the Divine in the other.” This kind of shared core belief is one of several, says Rabbi Melchior, that “are part of the fabric of the peace.”9 Melchior, Michael. “Establishing a Religious Peace.”In Kronish, Ron. Coexistence and Reconciliation in Israel, Paulist Press, 2015, p. 122. See also p.37 of this volume.Among other things, religious peace includes a signed written agreement that seeks to ‘resolve the conflict.’ Religious peace is discussed, and its catalyzing decisions are deliberated by senior (often illiberal) influential religious leaders and is based on deep religious convictions regarding the theology and religious law possessed by each side.10 See Zalzberg, Ofer. “Beyond Liberal Peacemaking: Lessons from Israeli-Palestinian Diplomatic Peacemaking.” Review of Middle East Studies, 53(1), 2019, pp. 46-53.

Religious peace does not mean that religious authorities have necessarily offered their support or ‘permission’ to a secular political peace process (as was common in the 1990s). Rather, it means seeing the very enterprise of peace (Shalom in Hebrew/Salam in Arabic) as the fulfilment of a religious obligation, and for some, as part of a prophetic mission and divine destiny – and not as an abrogation or compromise of one’s religious beliefs. The necessity for advancing religious peace in the Israeli- Palestinian conflict stems from the understanding that the conflict is not only a dispute between two national identities over scarce resources that can be divided up fairly through interest-based problem solving, but is also a collision of worldviews, in particular, those of religious Muslims – as represented by Hamas and the Islamic Jihad – and those of right-wing Torani religious Zionist Jews—who live over the Green Line, and strongly support the settlement movement.

According to these worldviews, the conflict is not just a real estate dispute that can be solved ‘rationally’ but concerns a God-given holy land that is undividable and whose material fate has cosmic consequences. The conflict is also deeply grounded in how each religious tradition sees the other through their religious worldview (how Jews are portrayed in Islamic texts and Gentiles in Jewish texts). Outsider governmental mediators have very little understanding of these core religious issues behind the conflict (besides, perhaps, how they manifest in Jerusalem) and have no means of engaging them constructively.

Only religious leaders serving as insider religious mediators – who have a deep understanding of the religious worldviews in question and possess strong ties to the most influential representatives of these views – are able to manifest a peace that includes these religious worldviews, as opposed to a ‘secular’ one that is predicated on their exclusion. Only the activity of such mediators has the potential for expanding what may be referred to as the ‘tent of peace.’11 For more about the concept of the ‘tent of peace,’ see Melchior, Michael. “Opening the Tent of Peace.” In Overland, G. et al., editors. Violent Extremism in the 21st Century: International Perspectives, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2018, pp. 447-452.

A Timeline of Insider Religious Mediation in the Context of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

A Timeline of Insider Religious Mediation in the Context of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

Since the beginning of the First Intifada in the late 1980s and even more so from the onset of the political peace process in the early 1990s, there have been a handful of religious leaders who function as insider religious mediators, informally and discreetly working together. Perhaps the earliest example of such insider religious mediators working together to mitigate a crisis- situation occurred in the context of Hamas’s abduction of Israeli soldier Nachshon Wachsman in October 1994. Following the kidnapping, Wachsman’s parents turned to Rabbi Menachem Froman to see if he could speak with his acquaintances in Hamas (through his connections with Sheikh Abdullah Nimer Darwish) and try to reach an agreement to release their son. Rabbi Froman related in an interview12 “Rabbi Froman: Hamas is more willing to compromise than the PLO” (interview), Channel 7, 23 Aug. 2008, https://www.inn.co.il/news/

Throughout the 1990s, Rabbi Froman and Sheikh Abdullah continued to approach senior religious and political leaders in efforts to include them in the concept of religious peace. Prof. Hillel Cohen, an Israeli scholar who studies and writes about Jewish-Arab relations in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, related in his eulogy for Rabbi Froman that, in 1996, Rabbi Froman worked out an agreement with senior Hamas leaders which would have brought about a ceasefire between Hamas and Israel as well as the release of Sheikh Ahmad Yassin.13 Zedekiah, Eran. “תמימי דעה ותמימי דרך“, [“Agree and Agree”], RegThink: The Regional Thinking Forum, 3 Oct. 2013, https://www.regthink.org

Since the beginning of the First Intifada in the late 1980s and even more so from the onset of the political peace process in the early 1990s, there have been a handful of religious leaders who began functioning as ‘insider religious mediators’ informally and discreetly working together, in particular Rabbi Menachem Froman and Sheikh Abdullah Nimer Darwish. Perhaps the earliest example of religious leaders serving as insider religious mediators attempting to work together to mitigate a crisis situation occurred in the context of the abduction of the Israeli soldier, Nachshon Wachsman in October 1994.

Following the kidnapping, Wachsman’s parents turned to Rabbi Froman to see if he could speak with his acquaintances in Hamas (through his connections with Sheikh Abdullah) and try to reach an agreement to release their son. Rabbi Froman, related in an interview many years later that he had reached a telephone agreement with Mahmoud al-Zahar, a senior figure in the Hamas political leadership, according to which Nachshon Wachsman would be released in return for the release of Hamas religious and political leader Sheikh Ahmad Yassin (1937 – 2004) from Israeli prison. However, when this agreement reached the hands of the Israeli prime minister at the time, Yitzhak Rabin, he replied that he (Rabin) does not make deals with Hamas. Wachsman was later killed by his hostage takers in a failed special forces attempt to free him. In an interview with Sheikh Abdullah in Haaretz (February 12, 1995), he also related how he had attempted to mediate between Hamas and Israel in various incidents, such as the abduction of Nachshon Wachsman, and how he had called upon Hamas to spare the lives of soldiers.

In January 2002, the first major public gathering of senior religious leaders organized by insider religious mediators took place: The Alexandria Summit of the Religious Leaders of the Holy Land. The primary insider religious leaders who helped make this happen were Rabbi Melchior (drawing on his influence both as a religious leader and, at the time, as Israel’s Deputy Foreign Minister), Rabbi Froman, Cannon Andrew White (the Archbishop of Canterbury’s envoy to the Middle East), and Sheikh Talal Sider (an Islamic religious and political leader from Hebron who was initially one of the founders of Hamas and later a minister in the Palestinian Authority).15 Sheikh Talal Sider, who testified that his own change of heart was a result of his many meetings with Rabbi Froman fell ill shortly after the summit and ultimately passed away in 2007. Rabbi Melchior described him as “a senior and full partner to attempts to persuade the leaders of the three faiths to turn religion into a lever for peace, brotherhood and hope.” See Landau, Yehezkal. Healing the Holy Land: Interreligious Peacebuilding in Israel/Palestine, United States Institute of Peace, 2003, p. 17, and Melchior, Michael. “Islam of a Different Kind,” Haaretz, 5 Mar. 2007, https://www.haaretz.com/1.4809166.

These religious mediators convened senior religious leaders for the first-ever religious peace summit to be held in the Middle East. The summit, despite taking place in the midst of the Second Intifada, received the endorsement16 Hranjski, Hrvoje. “Religious Clerics Gather in Egypt,” Midland Daily News, 19 Jan. 2002, https://www.ourmidland.com/news/article/Religious-Clerics-Gather-in-Egypt-7048808.php.of Israeli PM Ariel Sharon and Palestinian President Yasser Arafat. Participants included Rabbi Eliyahu Bakshi-Doron (1941- 2020, the Chief Rabbi of Israel), Sheikh Taisir Tamimi (Chief Justice of the Palestinian Sharia’ Courts), Sheikh Muhammad Sayyid Tantawy (1928-2010, at the time the Grand Mufti of Egypt and Grand Imam of Al-Azhar University, one of the most influential Islamic institutions in the Muslim world), the Archbishop of Canterbury George Carey, as well as other senior Muslim, Christian and Jewish religious leaders. It resulted in the Alexandria Declaration,17 Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The First Alexandria Declaration of the Religious Leaders of the Holy Land, 21 Jan. 2002,https://mfa.gov.il/MFA/MFAArchive/2002/Pages/The%20First%20Alexandria%20Declaration%20of%20the%20Religious.aspx.a statement undersigned by all participating senior religious leaders that killing “in the name of God” is a desecration of the Divine name and in which they pledged themselves to resolve their disputes peacefully, continuing “a joint quest for a just peace.”18 The complete document and list of participants can be found in English in a report by Yehezkel Landau for the United States Institute for Peace, “Healing the Holy Land: Interreligious Peacebuilding in Israel/Palestine,” Peaceworks, 51, 2003, pp. 16-23, 51-52.

Getting the various religious leaders to not only participate in this summit but also to agree on the exact language of the declaration was far from easy or straightforward, and took tremendous efforts by the insider religious mediators.19 Canon White describes in detail this challenge in Maring, Clayton. “War Junkie for G-d: Andrew White, Iraq.” In Dubensky, Joyce S., editor. Peacemakers in Action, Volume 2: Profiles in Religious Peacebuilding, Cambridge University Press, 2016, pp. 90-93.Though the summit and its declaration won praise from world leaders, it also received harsh criticism by those possessing more extremist worldviews, such as Hamas. Following the Alexandria Summit, there was a strong desire to continue to build on such a historic, successful gathering of religious leaders. In 2002, the Mosaica Center for Interreligious Cooperation was established by Rabbi Melchior, which engaged numerous Jewish and Muslim religious leaders in Israel primarily through joint educational activities. These interreligious educational programs continued to operate until 2015.20 See “Jews and Muslims Talk,” YouTube, uploaded by Mosaica – Religion Society & State, 11 May 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?

In 2005, participants from the Alexandria Summit, including Rabbi Melchior and Rabbi David Rosen, another well-known leader in advancing interreligious dialogue and peace, established the Council of Religious Institutions of the Holy Land (CRIHL).21 See “Council of Religious Institutions of the Holy Land: Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories,” Peace Insight, https://www.peaceinsight.org/en/organisations/crihl/.

The member institutions of CRIHL were the Chief Rabbinate of Israel, the leaders of the local Churches of the Holy Land, the Minister of the Islamic Waqf at the Palestinian Authority, and the Islamic Sharia Court of the Palestinian Authority. The members of the council pledged to strive in their roles as religious leaders “to prevent religion from being used as a source of conflict, and to promote mutual respect, a just and comprehensive peace, and reconciliation between people of all faiths in the Holy Land and worldwide.”22 Wang, Yvonne. How Can Religion Contribute to Peace in the Holy Land? A Study of Religious Peacework in Jerusalem (Ph.D. Thesis), University of Oslo, 2011, p. 198. For more about CRIHL see pp.197-209

CRIHL ceased to operate on a regular basis in 2013 but did reconvene to meet with Jason Greenblatt, the US administration’s Special Envoy for International Negotiations, in 2017.23 See Ahren, Raphael. “In ‘historic’ move, Trump envoy hosts the interfaith meeting,” Times of Israel, 16 Mar. 2017, https://www.timesofisrael.com/in-historic-move-trump-envoy-hosts- interfaith-meeting/#gs.fra0vm.

“Alexandria in the name of God: Leaders of religious institutions – Muslim, Jewish and Christian – came out yesterday with a joint declaration, ‘The Alexandria Declaration’, that sees murder in the name of God a desecration of the holy and a ‘pollution’ of religion. This is an impressive attempt, very relevant, to separate religion from terror.” Israeli journalist (Nahum Barnea/Yedioth Ahronoth, 2002)

The Alexandria Declaration in Hebrew and Arabic and image of participants (courtesy of Rabbi Melchior)

Rabbi Melchior with Pastor James and Imam Ashafa KAICIID conference, Vienna (2013)

In 2005, the first formal network of insider religious mediators was established. Mediators Rabbi Melchior, Sheikh Darwish and Sheikh Faluji, a former Hamas spokesman, established a strategic network between themselves and the centers at which they served as directors.24 “Rabbi, ex-Hamas and Muslim cleric unveil Mideast peace centres,” Jerusalem (AFP), 29 May 2005, https://www.spacewar.com/2005/050529163408.elpqov5r.html. (The original source doesn’t exist anymore)This partnership was initially referred to as “Alexandria Process Part II” and later renamed The Religious Peace Initiative in the Middle East (RPI). The three centers which make up the RPI are Sheikh Faluji’s Center in Gaza, Sheikh Abdullah’s Center in Kfar Kassem, both of which were later renamed the Adam Centers for Dialogue of Civilizations.25 See the Arabic-language website for Adam Center for Dialogue of Civilizations, https://www.adam.ps/.The center in Kfar Kassem was called specifically, The Adam Center for Interreligious Dialogue.and Rabbi Melchior’s Center Mosaica in Jerusalem, at which Rabbi Melchior continues until today to serve as president.

Together, these three insider religious mediators, with their centers and other partners, continued what had been started in the Alexandria Process. However, this time they aimed at engaging precisely the more extreme and influential religious leadership who were not part of the official Israeli or Palestinian establishment and who had been critical of the Alexandria Process. The goal was to reach out to the religious leaders who had far more influence on the religious worldviews involved in the conflict, namely the Islamic leaders aligned with Hamas and the larger, global Muslim Brotherhood movement and the right-wing, religious Zionist rabbis.

Today, the RPI continues to serve as a strategic network of insider religious mediators. Together, these insider religious mediators work to advance religious peace and help mitigate crisis-situations along the way. This is done through constantly expanding and strengthening their networks of relationships and trust with the most senior religious leaders in the Middle East who have direct influence over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. These crisis-situations can be of a religious nature, such as the Temple Mount/Al-Aqsa Crisis of 2017, or those that risk the lives of thousands, such as the coronavirus pandemic, on the occasion of which the RPI helped mediate between the World Health Organization (and Europe) and senior religious and medical leaders in the region.

In 2020, Mosaica, as part of the RPI, established a new initiative focused on engaging religious leaders on the community level called “Religious Leaders as Mediators.” The new initiative seeks to engage and train, separately, religious Zionist rabbis and Islamic Movement Sheikhs in both professional and traditional mediation to help them better mediate community conflicts. In parallel, Mosaica’s insider religious mediators work discreetly to connect religious Zionist rabbis with Islamic Movement sheiks, particularly within mixed Jewish-Arab cities and other areas within Israel where tensions are often high. The goals are for these local religious leaders to ultimately work together as insider religious mediators between their communities and advance religious peace and mitigate crisis situations as they arise.26 For more about Mosaica, see Mosaica.org.il

In 2020, Mosaica partnered with the World Health Organization (WHO) to combat misinformation and conspiracy theories about COVID-19 by working directly with local religious leaders. The Kavod-Karama (“Dignity”) Project was established to build on this success by proactively addressing challenges, including vaccination campaigns ahead of major Muslim, Jewish, and Christian holidays. The project organized forums that convened religious leaders with representatives from the WHO and Israel’s Ministry of Health, developed materials to aid practitioners and helped established partnerships between health professionals, policymakers, academics, and religious leaders to learn from COVID-19 and prepare for future health emergencies.

Case Studies of Insider Religious Mediation in the Context of the Israeli Palestinian Conflict

The following section presents several case studies of the interventions of insider religious mediators, and in particular, the RPI, operating in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. These case studies are based on published news articles and posts on social media and do not cover even a small fraction of the full extent of the behind-the-scenes activity constantly taking place, but they do serve as important examples of the nature of the activity. The case studies can be divided into three primary categories of activity: 1) Engaging with religious leaders in support of religious peace; 2) Preventing and responding to violence in the name of religion; and 3) Mediating crisis-situations in real time.

Insider religious mediators are often, as noted above, also religious leaders in their own right and as such are connected to religious leaders who are more senior than they are and who are extremely influential stakeholders in sustaining or mitigating the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The religious mediators are constantly strengthening their associations, leveraging them to arrive at higher tiers of leadership within the religious community. Therefore, it can be said that connections made in this context cannot be measured quantitatively but rather qualitatively. It can take a very long time to properly build one relationship and, in turn, bring that new leader to see themselves as an insider mediator who can provide a bridge to another leader, who is perhaps even more senior and influential. Once these relationships are established, they need to constantly be maintained and nurtured by virtue of the tangible results achieved by the connection (these results, however, do not always directly address the conflict). The primary means through which this ‘network building’ takes place is through the arrangement of small intimate and discreet meetings and occasionally larger gatherings, some of which are public.

Connecting Senior Religious Leaders to Religious Peace

Rabbi Melchior has, on several occasions, spoken of how he and his partners have conducted hundreds of sensitive meetings.27 See for example Ben-Dor, Calev. “‘Doing God’, or the importance of religious peacemaking: An interview with Rabbi Michael Melchior,” Fathom, Spring 2016, https://fathomjournal.org/ doing-god-or-the-importance-of-religious-peacemaking-an-interview-with-rabbi-michael- melchior/.

According to Rabbi Melchior, at these meetings and gatherings, some of the most extreme-leaning and influential religious leaders have the opportunity to encounter one another, build trusting relationships and commit to joining a network of religious peacebuilders and eradicating violence in the name of religion. Sheikh Ra’ed has also spoken about such meetings.28 See השיח ראיד באדיר, מנהל מרכז אדם לדיאלוג בין דתות – יוזמה דתית לשלום, [“Discourse with Sheikh Ra’ed Bader, Director of the Adam Center for Dialogue between Religions – Religious Peace Initiative”], YouTube, uploaded by Mosaica – Religion Society and State, 31 Mar. 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mkqUHqtB6IQ.

Though many, including Dr. Ali Sirtawi, Sheikh Imad, and Rabbi Gisser have reflected on their participation in such meetings, the content of these meetings remains completely secret.29 Feldinger, “Muslim leaders across the Middle East.”For example, in an article he published in the Israeli Newspaper Makor (“Peace of Believers,” September 18, 2020), Rabbi Melchior describes one particular meeting he and Sheikh Ra’ed attended, while still withholding identifying details:

“Several years ago, I traveled with my Muslim friends to a meeting, one of hundreds, with senior Islamic leaders […] as part of Mosaica’s Religious Peace Initiative in the Middle East. This meeting was not just another meeting. I waited months, perhaps years. The leader who I met with was the leading Islamic religious leader after the assassination of Sheikh Achmad Yassin [the leader of Hamas]. He and his family spent much time in jail with us [Israelis] […]. He agreed to meet with me in his home after much urging from his partners and his students, the most senior amongst them being the Sheikh Abdullah Nimer Darwish, of blessed memory.”30 Melchior, Michael, Facebook, 8 Sep. 2020,https://m.facebook.com/rabbi.melchior/posts/3940991432596048

Rabbi Melchior goes on to describe how they sat for seven challenging hours, during which they discussed religious principles of war and peace, Hudna (‘ceasefire’) as opposed to Salam (‘peace’) and how religious peace is what has been missing from the secular political peace processes. Then:

“The Sheikh was quiet. And then pounded on the table and said: “the young rabbi is right. There is a time for war and a time for peace.” Other than us, there were twenty people who sat the whole time quietly and vigilantly, religious leaders primarily from Hamas, who were in shock from the turn of events: “What will people say? Your whole life, you instructed us otherwise!” The Sheikh responded in a resolute manner: “No one ever presented peace as a religious project. And in addition, my whole life, I never was afraid of what people would say. I am only afraid of Allah.” We hugged, took a picture together, prayed each one in his own corner and we parted in peace.”31 ibid

Rabbi Froman worked very hard to constantly engage religious and political leaders in this way and had a unique method of trying to arrange meetings: through writing letters. Rabbi Froman sent countless letters to heads of state on their inauguration, well-known writers and thinkers (see, for example, his letter to Elie Wiesel in 2010), and religious leaders, urging them to consider his proposal of advancing peace through religion instead of without it. In 2008, Rabbi Froman, together with Gershon Baskin, a non-religious insider mediator, sent such a letter to Barak Obama shortly after his election victory.32 See Kershner, “From an Israeli Settlement.”They urged him and his new administration to think about Middle East peace differently than it had been conceptualized for the past 20 years. While Rabbi Froman never had the opportunity to meet with President Obama, he did meet with Turkey’s PM Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in 2010, with his partner and long-time Islamic peacemaker, Sheikh Ghassan Manasra.33 See “Jerusalem peacemakers visit Turkish PM over peace plan,” World Bulletin, 4 Jun. 2010, https://www.worldbulletin.net/diplomacy/jerusalem-peacemakers-visit-turkish-pm-over-peace-plan-h59484.html; See also Israeli News Channel Two, “ארדואן נפגש עם הרב פרומן” [“Erdoğan meets with Rabbi Froman”], 3 Jun. 2010, https://www.mako.co.il/newsmilitary/israel/Article-5c6e0801efef821004.htmThe meeting took place soon after the incident of the Mavi Marmara, which had significantly damaged Turkey-Israel relations.

Though much of the meetings and gatherings of senior religious mediators are discreet and far from the public eye, there have been a few public gatherings in which the mediators have brought senior religious leaders from both sides together as a show of support for religious peace. The first was The Alexandria Summit of Religious Leaders of the Holy Land in 2002. Over the years since, the RPI has continued to serve as the platform for numerous gatherings of religious leaders (such as in Norway in 2011 and in Athens in 2015) that are held secretly. In 2015, several of the RPI’s senior insider religious mediators – Sheikh Abdullah, Rabbi Melchior, Sheikh Ra’ed and Rabbi Gisser – all spoke as part of a panel at the Haaretz Peace Conference in Tel Aviv, with the title “Jerusalem and the Religious Aspect of the Conflict: Towards Reconciliation or Explosion?”34 See the complete video of the panel, פאנל – ירושלים והמרכיב הדתי של הסכסוך – פיוס או פיצוץ? – ועידת ישראל לשלום 2015, YouTube, uploaded by Haaretz, 12 Nov. 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Yea0- O7XVU&t=1892s.

This was a very rare occasion, in which these leaders spoke publicly about religious peace, even rarer in the context of a forum which is predominately liberal and secular. In such spaces, the notion of religious peace is considered, at best, exotic and, at worst, a threat to the predominating worldview of those involved. Indeed, Haaretz, who hosted the conference, did not bother to even mention in its articles on the event the historic speech of Sheikh Abdullah speaking about his involvement in advancing religious peace.35 The video of Sheikh Abdullah speaking at the״דברי שייח נימר דרוויש בוועידת השלום 2015״ conference was uploaded to YouTube by Haaretz, 12 Nov. 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watchapp=desktop&v=41i75A_y3ww&feature=youtu.be.

The most historic gathering of senior religious leaders since the Alexandria Summit of 2002 was the Alicante Summit of Religious Leaders for Peace in the Middle East, which took place in November 2016 in Alicante, Spain, under the official auspices of the Spanish Foreign Ministry36 Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores, Unión Europea y Cooperación, “Alicante Summit of religious leaders for peace in the Middle East (Press Release 240),” 14 Nov.2016, http://www.exteriores.gob.es/Portal/en/SalaDePrensa/NotasdePrensa/Documents/Religious%20leaders%20participating.pdfand the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations (UNAOC).37 “Remarks By H.E. Nassir Abdulaziz Al-Nasser The High Representative for the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations Summit for Peace in the Middle East,” unaoc.org, 13 Nov. 2016, https://www.unaoc.org/2016/11/summit-of-religious-leaders-for-peace- in-the-middle-east-alicante-spain/.The RPI’s senior religious mediators, including Rabbi Melchior, Sheikh Ra’ed, Sheikh Imad and Rabbi Gisser, participated and helped organize the historic conference.38 Sheikh Abdullah was unable to attend at the last moment due to health issues.

Like at the Alexandria Summit in 2002, one of the chief rabbis of Israel, Rabbi David Lau, and the Palestinian Authority’s top Sharia judge, Dr. Mahmoud al-Habbash – who also served as President Mahmoud Abbas’s advisor on religious and Islamic affairs – were in attendance. However, this time, more ‘extreme’ worldviews were also included. On the Jewish side, one of the most influential leaders of the Torani religious Zionist movement, Rabbi Yaakov Ariel, attended, and on the Islamic side, Dr. Naser al-Din al- Shaer (Senior Professor at Al-Najah University in Nablus, Minister for Education and Deputy PM) was scheduled to attend on behalf of Hamas in the Palestinian Cabinet.39 “Religious leaders participating at Summit for Peace in the Middle East, Alicante, 14 and 15 November 2016,” http://www.exteriores.gob.esPortal/en/SalaDePrensa/

The participants, even those advocating for the more extreme worldviews, condemned all religious violence, undersigning a statement that declared “the proper means of solving conflict and disagreement is by negotiation and deliberation only” and pledged “to relentlessly seek peace in the Land.” The historic summit was covered in the English-, Hebrew– and Arabic-language media.40 See for example Sharon, Jeremy. “Jewish and Muslim Leaders call for end to violence and incitement,” 17 Nov. 2016, Jerusalem Post, https://www.jpost.com/arab-israeli-conflict/jewish-and-muslim-leaders-call-for-end-to-violence-and-incitement-472930; Times of Israel Staff. “Hamas-linked imam, Israel chief rabbi unite in call for peace,” Times of Israel, 19 Nov. 2016, https://www.timesofisrael.com/hamas-linked-imam-israel-chief-rabbi-unite-in-call-for-peace/; “רבנים ישראלים, ושיח’ים פלסטינים נפגשו בוועידה בספרד”, Makor Rishon, 17 Nov. 2016, https://www.makorrishon.co.il/nrg/online/1/ART2/847/879.html.

Religious Leaders for Peace in the Middle East Summit (Alicante/Spain, 2016)

A year later, in 2017, at the invitation of UNAOC, many of the senior insider religious mediators and leaders who had attended and helped organize the Alicante Summit – including Rabbi Melchior, Sheikh Ra’ed, Sheikh Imad, Dr. Nasser, and Rabbi Gisser, as well as Rabbanit Bar Shalom – presented their work at the special session on “The Role of Religious Leaders in Peacebuilding in the Middle East” at the United Nations in New York City.41 See the brochure for this event at https://www.unaoc.org/wpcontent/uploads/religious- leaders-v5-final3.pdf.final3.pdf.

Video of complete conference at the UN, (photo courtesy of Rabbi Melchior, July 19, 2017)

Preventing and Responding to Violence in the Name of Religion

Preventing and responding to violence in the name of religion has been a central prerogative of religious mediation since the Alexandria Declaration in 2002, which stated, “The Holy Land is holy to all three of our faiths. Therefore, followers of the divine religions must respect its sanctity and bloodshed must not be allowed to pollute it.”42 See the brochure for this event at https://www.unaoc.org/wpcontent/uploads/religious- leaders-v5-final3.pdf.This notion was later reaffirmed in the Alicante Declaration, which stated that “[t]he violence that is conducted, supposedly in the name of God, is a desecration of His name, a crime against those who are created in His image, and a debasement of faith. The proper means of solving conflict and disagreement is by negotiation and deliberation only.”43 Landau, “Healing the Holy Land,” p. 51.Therefore, insider religious mediators invest a significant amount of time and effort in addressing violence, whether it be to try and prevent it or to respond to it with clear denunciations.

Insider religious mediators, because of their vast network of connections to other religious leaders within their respective religious communities, have played important roles in mitigating crisis-situations in mixed Jewish-Arab cities within Israel. Often, religious Jewish Israelis and Islamist ‘Palestinians of ‘48’/ Israeli-Arabs live in the same neighborhoods within these mixed cities, which leads to constant conflict. These mixed cities, in certain ways, are microcosms of the larger Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Tensions in these cities are always high, but particularly so around religious holidays. In 2008, rioting broke out in the mixed city of Acre due to an incident between Jews and Arabs that had taken place on the holiest day in Judaism, Yom Kippur. Rabbi Melchior and Sheikh Abdullah quickly made public calls for peace. Drawing on religious symbolism from the Jewish festival of Sukkot, which immediately follows Yom Kippur and commemorates the temporary shelters built by the Israelites on their way from Egypt to the Promised Land, the religious leaders sat together in a Sukkah (‘tent’) which they called the “Sukkah of Peace.” Rabbi Melchior condemned the violence that had broken out between Jews and Arabs in the city: “We will not accept any form of incitement […] In Israel’s sukkah, there must be room for its Muslim and Christian citizens. We must cast out those who incite, and who hate, and leave room only for the good.”44 Einav, Hagai. “Hundreds gather at Akko ‘Peace Sukkah,’” ynetnews.com, 15 Oct. 2008, https://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-3609256,00.html.

Rabbi Melchior, Sheikh Namir Darwish meet at ‘Peace Sukkah’ (George Ginsburg/Ynet News, 2008)

In 2014, the most somber day in Judaism, Yom Kippur, and the most joyous day of the Islamic calendar, Eid Al-Adha, fell on the same day. There was once again a concern which prompted Israeli police warnings that there would be an eruption of violence, particularly in mixed Jewish-Muslim cities within Israel, such as had taken place in Acre in 2008. This time, Rabbi Melchior and Sheikh Ra’ed Bader reached out to the most ‘radical’ Muslim leaders and asked for their support in attempting to avoid violence. The Muslim leaders issued a historic Fatwa that was published in the Arabic language press and posted on the walls of mosques calling on their co-religionists to respect Yom Kippur, while, in parallel, Rabbi Melchior arranged for senior rabbis to publish a statement explaining the significance of Eid Al Adha45 Melchior, “‘Doing God.’” Rabbi Melchior and Mosaica also arranged a series of meetings between rabbis and imams, so that they could inform themselves regarding the sensitivities involved with each holy day, encouraging them to work together to prevent violence. In addition, Mosaica’s Tochnit Gishurim – a project which supports tens of ‘community mediation and dialogue centers’ throughout the country, including in the mixed cities – held a number of events and meetings in these cities promoting nonviolence and tolerance on this sensitive, dual holy day. Their joint efforts and the efforts of their partners contributed to preventing violence from breaking out on that day.46 Lidman, Melanie. “Leaders bid to downplay tensions as Yom Kippur, Eid al-Adha clash,” Times of Israel, 2 Oct. 2014, https://www.timesofisrael.com/ leaders-bid-to-downplay-tensions-as-yom-kippur-eid-al- adha-clash/.

In November 2019, the RPI’s senior insider religious mediators, together with Mosaica’s Center for Conflict Resolution through Agreement’s senior professional mediators, presented to the top 300 Israeli police officers about their work in mitigating this crisis-situation and practical lessons that can be learned from it moving forward.

Fatwa (Islamic ruling) to respect Yom Kippur and celebrate Eid Al-Adha

Rabbi Melchior speaking about the role of religious leaders preventing violence on Yom Kippur/Eid Al-Adha to top Israeli police officers (November, 2019)

Religious leaders – such as Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi , one of the most influential Islamic authorities in the world – have had a direct impact on the level of violence in the region through their rulings, such as through permitting suicide attacks carried out by Hamas against Israelis. In direct opposition to this religious position, Sheikh Abdullah wrote a controversial book in 1999 (Auqifu Al-Siyasat Al-Intihariya Li-Hukumat Al-Istitan Al-Israeiliya), in which he openly spoke out against suicide bombings being carried out in the name of Islam against Israel.

Years later, in 2016, Sheikh Qaradawi openly reversed his ruling on suicide bombings on Saudi TV, stating that such acts were no longer permitted.47 See Sheikh Salman al-Awda’s interview of Sheikh Qaradawi on the Saudi TV channel Al-Hiwar.الشيخ سلمان العودة يحاور العلامة يوسف القرضاوي في لقاء خاص على قناة الحوار, YouTube, uploaded by Al Hiwar TV, 18 Nov. 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C825fzdDm6A.This historic change in religious ruling attracted the attention of the well-known Israeli journalist Zvi Yehezkeli, who reported about it on Israel’s Channel 13.48 See program;לונדון את קירשנבאום, [“London et Kirshenbaum”], Channel 13, 28 Nov. 2016, https://13news.co.il/item/programs/london-and-kirshenbaum/episodes/ntr1220842/, 24:00 (of 48-minute video).

Image of book

Watch the full video

Rabbi Melchior, in his 2016 article “Don’t dismiss the Islamic ruling on suicide attacks,” explained some of the backstory of this momentous occasion:

“Why did Sheikh Qaradawi reverse his ruling and why now? Just prior to announcing his decision on Saudi television, Qaradawi met with Dr. Nasser al-Din al-Shaer, a renowned Islamic scholar, former deputy PM for Hamas in the joint Fatah-Hamas Government and a key Palestinian figure in an initiative my colleagues and I have been working on for several years[, t]he Religious Peace Initiative […]. Al-Shaer reported to Qaradawi about the Religious Peace Initiative and its unique approach of pursuing peace by including, rather than ex-cluding, religious Jews and Islamists. Al-Shaer also requested Qaradawi’s support and blessing for the Initiative and asked him to publicly renounce his earlier fatwa. Qaradawi reported this meeting on his website and took to the airwaves.”49 Melchior, Michael. “Don’t dismiss the Islamic ruling on suicide at- tacks,” Times of Israel, 16 Jan. 2016,https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/dont-dismiss-the-islamic-ruling-on-suicide-attacks/.

Religious leaders who are also insider religious mediators will often be the first to denounce acts of ethnonational violence and, in addition, take action to engage others, often more senior religious leaders, to make similar declarations denouncing violence, to visit the scene of the crime and/or to visit with survivors. Sheikh Abdullah and his followers in the Southern Branch of the Islamic Movement consistently and sharply condemned the suicide bombings that were carried out by Hamas and Islamic Jihad in early 1996 on the pretext that murder is forbidden, regardless of the murder’s context or the motives for carrying it out. Years later, Sheikh Ra’ed, Sheikh Abdullah’s primary disciple and the leading Islamic authority of the Southern Branch, publicly denounced the violent murder of the Jewish Fogel Family in 2011.50 11 March 2020, ““,לפי ההלכה המוסלמית מגיע לרוצחים מאיתמר עונש מוות [“According to Islamic Law, The Murderers of Itamar are Liable the Death Penalty”], https://www.mako.co.il/opinionsarticles/Article9a0dc813053de21006.htm.

Jewish-Israeli insider mediators have often acted quickly to denounce acts of violence done by Jews to Palestinians as well. Usually, this meant reaching out and engaging more senior religious leaders to denounce the violence or pay a visit to the victims. In 2001, Chief Rabbi Bakshi-Doron sent a letter through Rabbi Froman to Yasser Arafat denouncing the murder of three Palestinians at the hands of Jewish-Israeli extremists. Rabbi Froman was consistently one of the first both to denounce acts of Jewish violence against Palestinians and to visit the sites where they occurred and pay respects to the victims; for example, following the burning of the Mosque in Lubban al-Sharqiya on May 4, 2010, by Jewish extremists51 YouTube, uploaded 6 May 2020 by Asaf Perry,”,הרב מנחם פרומן לאחר פעולת תג מחיר במסגד בלובן א שארקיה” https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=QdUk8yo9m9A& feature=related.Several months later, on October 5, 2010, another mosque was burnt in the West Bank village of Beit Fajjar. This time Rabbi Froman came to visit the mosque with Rabbi Aaron Lichtenstein and Rabbi Shlomo Risken, religious Zionist rabbis from the West Bank who were more senior than himself and, what is more, not generally aligned with his peacebuilding activities.52 See picture of the religious leaders, “An Israel soldier and a settler rabbi” (image), Getty Images, 5 Oct. 2010, https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/an-israeli-soldier-anda-settler-rabbi-talk-to-palestinian-newsphoto/104793963.

In the summer of 2015, following the horrific Duma Arson Attack, Rabbi Melchior was approached by the heads of the National Religious rabbinic organization Tzohar to plan a condolence meeting with the family.53 See Kempinski, Yoni. “Tzohar Rabbis Visit Arson Victims,” Israel National News, 3 Aug. 2015,https://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/198983.They did not have the contacts to arrange it. Rabbi Melchior, together with his partner Sheikh Abdullah, arranged a meeting at the Sheba Medical Center in Israel, where members of the family were being treated at the time.54 See “Tzohar Rabbonim Make a Joint Visit to Victims of Duma Arson Attack with Clerics of Other Religions,” The Yeshiva World, 3 Aug. 2015, https://www.theyeshivaworld.com/news/ headlines-breaking-stories/331413/tzohar-rabbonim-make-a-joint-visit-to-victims-of-duma- arson-attack-with-clerics-of-other-religions.html.

The Jewish delegation included the Chief Rabbi of Jerusalem, Rabbi Aryeh Stern, and the heads of the Tzohar organization, Rabbi David Stav and Rabbi Rafi Feurstein. The group of rabbis, together with Rabbi Melchior, Sheikh Abdullah, and Sheikh Ra’ed, met with the surviving family members and expressed their commitment to ongoing peace efforts and dialogue.55 For a complete video of the visit of the rabbis see Blumenfeld, Revital. “אביו של אבו חאדיר ביקר את משפחת דואבשה” [“The father of Abu Hadir visited the Duabsha family”], (video), Walla, 3 Aug. 2015, https://news.walla.co.il/item/2878563

Watch the full video

Speaking out against violence has come to also include speaking out against antisemitism and islamophobia. Rabbi Melchior and Sheikh Abdullah made a pact that every time there is an act of antisemitism, Sheikh Abdullah would speak out against it, and every time there is an act of islamophobia, Rabbi Melchior would do the same. In 1998, a young Russian immigrant created caricatures of the prophet Mohammed in the form of a pig which she distributed around Hebron56 See Schmemann, Serge. “A day in court for Israeli who enraged Muslims,” New York Times, 19 Jul. 1997, https://www.nytimes.com/1997/07/19/world/a-day-in-court-for-israeli-who-enraged-muslims.htmlThis enraged the locals, who saw it as a blasphemous attack on Islam. President Ezer Weizman and Israel PM Netanyahu condemned the act, but this was not enough to defuse the rage. Rabbi Melchior, in his Facebook post eulogizing the passing of Chief Rabbi Eliyahu Bakshi-Doron (1941-2020), tells of how he heard from his Palestinian contacts that in the wake of the incident the imams in Hebron were preparing incendiary sermons to deliver in the mosques, which could have inflamed violent riots.57 Melchior, Michael, Facebook, 16 Apr. 2020, https://m.facebook.com/315417618486799/posts/3482920515069811/extid=xkb7LkHIWO94sVUJ&d=nHe understood that there was a need for a religious voice (and not just political voices) to win the confidence of the Muslim leadership and therefore brought Chief Rabbi Bakshi-Doron to Hebron, where they met with the Grand Mufti of Hebron. The Chief Rabbi explained that the woman’s actions were an abomination according to Jewish law. The Mufti was reassured by this response from the highest Jewish authority in Israel. He calmed the imams and, in so doing, avoided potential bloodshed.

In 2007, Sheikh Abdullah was the first Muslim leader to have ever spoken at the Global Forum for Combatting Antisemitism, which convened that year in Jerusalem.58 Gur, Haviv Rettig. “Islamic Mov’t: Muslims have accepted 2- state solution,” 11 Feb. 2007, Jerusalem Post, https://www.jpost.com/Middle-East/Islamic-Movt-Muslims-have-accepted-2-state-solutionHe declared, “I am a soldier, and hopefully the lead soldier, in the war against anti-Semitism and Islamophobia in the region.” In the same speech, Sheikh Abdullah sharply criticized anyone who denies the Holocaust, including Iranian President Ahmadinejad: “Tell anyone who denies the Holocaust: ‘Go ask the Germans, did you do it or not?’’59 Barkat, Amiram.”השייח דרוויש גינה הכחשת שואה והצהרות אחמדינג’אד“, “HaSheikh Darwish genah hachashat Shoah vehatzarot Ahmadinejad”, Haaretz, 2 Feb. 2007,https://www.haaretz.co.il/misc/2007-02-11/ty-article/0000017f-f702-d318-afff-f7638bb30000In April 2020, MK Dr. Mansour Abbas, from the Ra’am party, which is connected to the Southern Branch of the Islamic Movement, delivered a historic speech on the occasion of Holocaust Remembrance Day, in which he attested, “As a religious Palestinian Muslim Arab, who was raised on the legacy of Sheikh Abdullah Nimer Darwish, who founded the Islamic Movement, I have empathy for the pain and suffering over the years of Holocaust survivors and the families of the murdered.”60 See “Arab-Israeli lawmaker honors Holocaust victims at Knesset,” i24News, 21 Apr. 2020, https://www.i24news.tv/en/news/israel/1587474273-history-made-after-arab-israeli-lawmaker-honors-holocaust-victims-at-knesset. See also Wolf, Etzeek.News1, 21 Apr. 2020, https://www.i24news.tv/en/news/israel/1587474273-history-made-after-arab-israeli-lawmaker-honors-holocaust-victims-at-knesset

It is also important to note in this context the historic visit by Sheikh Muhammad bin Abdul Karim Issa, Secretary General of the Muslim World League (based in Saudi Arabia), to Auschwitz in January 2020.61 See Schwartz, Yaakov. “This must never happen again, says Saudi cleric as Muslim group tours Auschwitz,” Times of Israel, 24 Jan. 2020, https://www.timesofisrael.com/this-must-never-happen-again-says-saudi-cleric-as-muslim-group-tours-auschwitz/#gs.fsm49i; and i24 News, 24 Jan. 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uFwDsCjn-Qs.The trip took place together with tens of other Islamic leaders and leaders of the American Jewish Committee and was an important step toward advancing religious peace between Jews and the Muslim world.

Watch the full video

Mediating Crisis Situations in Real Time

A very significant amount of the religious mediators’ time and resources are invested in discreetly responding to and mitigating crisis-situations behind the scenes, as they arise in real-time. These situations, in turn, also strengthen their networks and standing within and between their communities. Rabbi Melchior says that his network of religious mediators is constantly intervening to maintain peace, efforts that are not restricted to religious contexts.62 Feldinger, “Muslim leaders across the Middle East.”Rabbi Melchior has also shared that most of their work takes place quietly and confidentially and each success is built on the relationships that the insider religious mediators have developed with one another.63 Klein, Zvika. “‘הרב מיכאל מלכיאור: ‘השלום לא יבוא מבחוץ“[Rabbi Michael Melchior: Peace Will Not Come From Out There”], 4 Mar. 2018, Makor Rishon,https://www.makorrishon.co.il/judaism/25715/.

As noted above, Rabbi Froman and Sheikh Abdullah already began working to advance religiously sanctioned ceasefires and hostage exchanges between Hamas and Israel in the mid-90s, such as in the context of a kidnapped Israeli soldier, Nachshon Wachsman, who was held hostage by Hamas in 1994. Over the years since Rabbi Froman continued to conduct meetings to advance ceasefires as well as hostage exchanges. On June 26, 2006, it was reported that Rabbi Froman was blocked by Israeli forces in the middle of conducting a meeting in Jerusalem with senior Hamas leaders, including Mahmoud Abu-Ter and Israeli MK Ibrahim Sarsour (who had taken over for Sheikh Abdullah as leader of the Southern Branch of the Islamic Movement).64 See “This was 2006,” passia.org, 26 Jan. 2006 http://passia.org/media/filer_public/f7/07/f70733ec-3cad-4fa6-8d73-16b826c66246/palestine_in_review_2006.pdf, P.4.The meeting purportedly concerned the announcing of a ceasefire between Hamas and Israel. On February 15, 2008, Rabbi Froman, together with a Palestinian journalist with close ties to Hamas, Khaled Amayreh, attempted to mediate a ceasefire and hostage exchange between Israel and Hamas.65 See Cobban, Helena. “Video of Froman and Amayreh discussing Accord,” 15 Feb. 2008, https://vintage.justworldnews.org/2008/02/page/2/; and Etinger, Yair, Haaretz, 3. Feb. 2008, “רב ועיתונאי פלשתינאי ניסחו הצעה לשחרור גלעד שליט” [“Rabbi and Journalist Drafted Proposal for Release of Gilad Shalit”],https://www.haaretz.co.il/misc/1.1302462Rabbi Froman and Amayreh connected senior religious leaders in Turkey with senior religious leaders in Israel in order to try and bring about the release of Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit, held by Hamas, as well as a ceasefire between Hamas and Israel.

Another example of insider religious mediators operating behind the scenes in hostage situations is the Siege of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, from April 2 to May 10, 2002, only months after the Alexandria Summit. Canon White describes in great detail how he, together with Rabbi Melchior and other insider religious mediators who had participated in the summit, engaged in intense shuttle diplomacy between the various religious and political leaders until it was resolved.66 See Maring, “War Junkie,” pp 93-95.

Perhaps the most profound example of the RPI’s insider religious mediators mitigating crisis situations took place after two Muslim ‘Palestinians of ‘48’/Israeli- Arabs killed two Israeli police officers on the Temple Mount/Al-Aqsa Mosque on July 14, 2017. Israeli police subsequently put up cameras and metal detectors at the entrance to the Temple Mount/Al-Aqsa, which led to calls of violence in what became known as the Temple Mount/Al-Aqsa Crisis.67 See Mason, Simon J.A. “Local Mediation with Religious Actors in Israel-Palestine.” In CSS Analyses in Security Policy, 281, p. 4, Apr. 2021.The installation caused great offense to the Muslim world and the situation was inflamed by extremists who wanted, according to Rabbi Melchior, to use the sensitivity of the site for Jews and Muslims “to create a world war, a clash of civilizations.” Riots broke out on the Temple Mount/Al-Aqsa in East Jerusalem and in the West Bank, with several fatalities. Since the Israeli government had no channels of communication with senior Palestinian religious leaders, they were unable to defuse the rage. The Jerusalem Police, who had a good relationship with Mosaica due to years of receiving cultural sensitivity training from Mosaica’s Center for Conflict Resolution through an Agreement, appealed to Rabbi Melchior, the President of Mosaica, for help. The police knew of his relationships with senior Islamic leaders (in part thanks to Rabbi Melchior’s 2014 intervention in the mixed cities, as discussed above). These relationships enabled him, together with the other senior insider mediators, to meet the leaders of the Waqf, or the Muslim authority, responsible for overseeing the Al-Aqsa Mosque. According to Rabbi Melchior, they negotiated non-stop for a week in order to come to a solution “before the whole Middle East went up in flames.”68 Ibid. Finally, they forged an agreement “with the support of a lot of players in the Muslim world and the Israeli police” that was also “approved by the Israeli cabinet.” The metal detectors were removed, and the Waqf successfully reclaimed responsibility for ensuring quiet as before.69 See interview of Rabbi Melchior with Israeli journalist Aharon Barnea, 6 Aug. 2017, uploaded by Israeli Knesset TV Channel, “אהרן ברנע מראיין את הרב מיכאל מלכיאור” [“Aharon Barnea Interviews Rabbi Michael Melchior”], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f0gSUL6m3f8.

The intervention provides a rare example of the very sensitive process of insider religious mediation being shared with the press, demonstrating the significance of the role the RPI can play in a crisis-situation.70 Nachshoni, Kobi. “Israeli-Palestinian peace initiative helped resolve Temple Mount standoff,” 29 Jul. 2017, https://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-4995939,00.htmlThe intervention was, however, strongly criticized by the deputy chairman of the Northern Branch of the Islamic Movement, Sheikh Kamal Khatib.71 “القدس الفاضحة!!!!” [“Jerusalem the Scandalous”], https://www.mawteni48.com/archives/2415. Both Sheikh Imad and Dr. Nasser later denied Sheikh Khatib’s accusation that they had been involved in mediating the crisis. See “حماس اﻟﻀﻔﺔ ﻏﺎﺿﺒﺔ ﻋﲆ اﻟﻈﻬﻮر اﻟﺪﺣﻼني ﰲ ﻏﺰة,” [Hamas of the West Bank Fumes at Dahlan’s Appearance in Gaza”], 29 Jul. 2017, https://nn.najah.edu/news/Report-1/2017/07/29/41727/.

Muslim worshiper praying outside Al-Aqsa (Ynet News, 2017)