Palestinian Governance

A majority of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza have had a limited form of self-government since 1994, though over time they have faced steadily increasing constraints on even this limited autonomy. Some constraints result from continued Israeli military control, and others are internal, including the deep ideological, political, and geographic divide between the West Bank and Hamas-ruled Gaza.

Despite some assessments in the international community that the Palestinian Authority–the recognized body established by the Oslo peace Accords–is ready for statehood, overcoming current constraints will be essential if a state is to emerge that is functional and part of a negotiated agreement with Israel.

President Mahmud Abbas, center, meets with the newly announced government (Fadi Arouri/AFP/Getty Images, 2019)

October 7th Update

None of the U.S. allies in the region are willing to contribute any money to the rebuilding of Gaza without a political process that returns Gaza to Palestinian governance and establishes a pathway towards a Two-State Solution. Likewise, to be in a position to participate in the governance of Gaza, the Palestinian Authority is being asked to substantially reform itself, eliminate its prisoner payment system, and implement transparency, education and democratic reforms to name a few. While Israel will not countenance a role for Hamas in the future governance of Gaza, Palestinians assert that national religious voices – label them Hamas or something else – must be included within the Palestinian governing structure if it is to enjoy legitimacy in Gaza after the war.

BACKGROUND

From 1948-1967, Palestinians in the West Bank and East Jerusalem lived under Jordanian control and Palestinians in Gaza lived under Egyptian control. From 1967 until the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993, all Palestinians in the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem lived under Israeli control.

Following Israel’s annexation of East Jerusalem in 1967 (reaffirmed in 1980), Palestinians there were not fully absorbed into Israel. Although enjoying some rights as “residents” of Jerusalem, for the most part this Palestinian sub-population has a reality all its own: not fully part of Israel and not fully part of the self-governing framework for Palestinians in the West Bank.

Israeli leaders and soldiers after the capture of the Temple Mount/Haram Al-Sharif in the Old City of Jerusalem (Hulton Archive/Getty Images, 1967)

Palestinian political institutions, most notably the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), existed largely in exile. Although the principle focus was waging armed struggle and violence against Israel, groups like the PLO (created in 1964) did maintain some degree of connectivity with the local population and did maintain limited social welfare programs with Palestinian populations, especially the refugee population in surrounding countries.

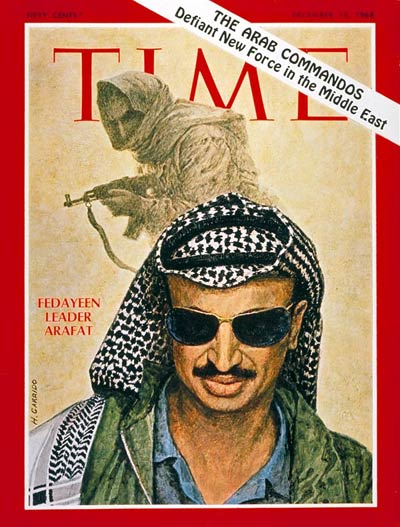

Yasser Arafat on the cover of Time magazine (1968)

Yasser Arafat at the UN (1974)

Left: Yasser Arafat on the cover of Time magazine (1968)

Right: Yasser Arafat at the UN (1974)

On the question of governance, there are two important inflection points to keep in mind. First, the notion of Palestinian autonomy as an interim stage toward resolving the conflict was first introduced as part of the 1978 Camp David Peace Accords between Israel and Egypt.

Expected to last five years, and intended to build confidence and political support for a permanent negotiated settlement, the proposal embedded in the Israeli-Egyptian peace process did not catch on at the time. PLO leaders, and other Arabs, opposed the idea and continued acts of violence and terrorism against Israel.

Deeply opposed to Egypt’s peace treaty, Palestinian leaders continued to refuse to recognize Israel. With the end of the Cold War, the U.S.-led victory in the first Gulf War and decisions by Palestinian leaders to end violence and recognize Israel, a second inflection point emerged. Following the 1991 Madrid Peace Conference, which launched the first direct peace talks between Israel and all of its Arab neighbors, and then the 1993 Israeli-Palestinian Oslo agreement, Palestinian autonomy again became a focus of diplomacy.

Borrowing this earlier idea from the Israel-Egypt peace process, Israeli and Palestinian leaders designed a self-governing framework that was intended to 1) reinforce mutual recognition, 2) build trust for later stages of peacemaking, 3) produce tangible economic and social benefits for Palestinians in the territories, and 4) provide Palestinians with a significant measure of self-governance and allow Israel to withdraw a large measure of its military control over their lives.

Palestinian autonomy officially began in 1994 with the Israeli withdrawals from populated areas in Gaza and the West Bank town of Jericho, which were led by a newly created “Palestinian Authority,” led by Palestinian leaders who returned from exile. From the start, Palestinians maintained a dual structure of newly created self-governing institutions and political parties, like the PLO, which continued to control areas excluded from the autonomy framework, like foreign affairs and diplomacy.

Israel and the Palestinian Territories

Through a series of interim peace agreements concluded over several years, the Israeli military withdrew from most Palestinian cities and towns, and the Palestinian Authority expanded its reach.

The Oslo process envisioned an expansive framework of Palestinian autonomy, covering vast areas from policing and intelligence, to education, trade and social welfare. The concept was also premised on close cooperation with Israel, in virtually all fields, from the economy to security.

Setting up and operating a Palestinian self-governing authority was more complex than anticipated. Not only was the returning PLO leadership not well versed in managing public institutions, but early waves of Palestinian terrorism and continued Israeli military control left the Palestinian population increasingly facing extended closures and lockdowns.

With the collapse of the peace process in 2000 and the outbreak of the Second Intifada, massive waves of violence unfolded, with staggering civilian casualties in both societies. The Israeli military returned to the areas it had previously withdrawn from and Israel built a “separation barrier” following dozens of Palestinian terrorist attacks against Israelis in the early 2000s. Many expected the Palestinian Authority would collapse, but throughout these tumultuous years there was a basic, if informal consensus that Palestinian self-governing institutions should remain intact.

For many years, corruption and inefficiencies also plagued Palestinian public institutions, though performance improved measurably over time, particularly with increasing pressure from international donors in the early 2000s. By 2011, the United Nations envoy declared that Palestinians were ready for statehood, a view echoed by the World Bank, IMF and other members of the international community around this time.1 See Joel Greenberg, “U.N. Report Says Palestinian Authority Ready for Statehood,” Washington Post, April 12,

2011. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/un-report-palestinian-authority-ready-for-statehood/2011/04/12/AFoKaUSD_story.html

But major constraints on self-governance have only grown with time, the most serious of which have been the surprise Hamas victory in Palestinian legislative elections in 2006 followed by the group’s violent takeover of the Gaza Strip the next year, causing a serious political, ideological and geographic split and eliminating much of the Palestinian Authority’s reach in the heavily populated coastal enclave.

SCOPE OF SELF GOVERNANCE TODAY

Palestinian self governance is strongest and most reliable in the West Bank, and in the areas of education, health, welfare, public finance and municipal services. Security is an important sector as well, though highly constrained.

Palestinian governance is dramatically weaker in Gaza, where the population is much poorer, under the control of the terrorist group Hamas, more impacted by repeated rounds of violence with Israel, and therefore more reliant on emergency humanitarian assistance, provided principally by the United Nations.

List of PA ministries as of 2019

Below are several examples of areas in which Palestinians exercise a fair degree of autonomy.

Education

The Palestinian Authority supports a vast network of schools and universities, where a majority of Palestinian young people in the West Bank study. The education sector, in terms of content, curriculum, hiring, and infrastructure, is widely seen as the area in which Palestinians exert the greatest degree of autonomy. A U.N. school network continues to serve part of the refugee population in the West Bank, and increasingly large swaths of the Palestinian population in the impoverished Gaza Strip.

Health

The Palestinian Authority supports a wide network of health clinics and hospitals, and maintains working relations with Israel in terms of the provision of Israeli care for Palestinians when care is unavailable in the territories. Palestinian health care institutions in East Jerusalem are partially affiliated with this system. Some important health institutions continue to be run by international donors, but in coordination with the Palestinian Authority.

People walk outside of the Augusta Victoria hospital in East Jerusalem (AFP, 2018)

Municipal Services

The Palestinian Authority manages a wide range of municipal services, from trash collection to permitting, but these are also constrained by the realities of Israeli military control over a majority of West Bank land.

Security/Policing/Rule of Law

Palestinians are not in control of their national security, but they do exercise a fair degree of autonomy in terms of local policing, justice and the rule of law. Palestinian courts and prosecutors operate and are accountable to PA leaders. The U.S. plays a quiet, yet central role in Palestinian-Israeli security cooperation, as part of a program established by President George W. Bush and funded by the U.S. Congress.

Palestinian police (Interpol)

Palestinian security forces enforce COVID-19 lockdown (AFP, 2020)

Left: Palestinian police (Interpol)

Right: Palestinian security forces enforce COVID-19 lockdown (AFP, 2020)

LIMITATIONS

Limitations by agreement

By agreement with Israel, the Palestinian Authority accepted stringent limitations on its security services (both scope and weaponry) and its conduct of foreign relations. The PA also entered into a customs arrangement with Israel whereby imported goods pass through Israel, which collects and passes along custom duties, though these have been suspended in times of tension. For practical reasons, Palestinians also accepted constraints in areas like monetary policy and do not have their own currency.

Limited reach

The Palestinian Authority’s limited self-governance does not extend to Palestinians in East Jerusalem and, since 2007, to most of the population in Gaza. Neither does the PA represent the large Palestinian populations in neighboring countries, which are represented by local governments and a variety of Palestinian political parties, including the PLO.

Settlements/settlers

Israeli measures to protect settlements and ensure their connectivity with Israel also place a variety of constraints on Palestinian self-governance, including restricting freedom of movement and the use of natural resources, especially in adjoining areas. A common complaint of Palestinians is that Israeli settlements continue to expand.

Israeli restrictions on land use

Other than most Palestinian cities and towns (known as areas “A” and “B”)—which is 40 percent of the West Bank—Israel controls land use and places restrictions on Palestinian development, including roads, housing and infrastructure.

Palestinian Elections

The Palestinian Authority Executive and the Legislative Council, elected in 2005 and 2006 respectively, are a decade past their initial term. Palestinian elections require consent from the PA, Hamas and Israel (to enable Palestinians in East Jerusalem to vote) in order to take place. Since 2006, despite many agreements between Hamas and Fatah, no election has been conducted. these failures continue to rode democratic legitimacy of Palestinian self-governance.

Despite many attempts to hold elections after the political split between Hamas and Fatah, the most recent being in May 2021, but the parties have been unable or unwilling to hold further parliamentary or presidential elections.

DIGGING DEEPER

*These materials are provided for reference purposes, with no intention of endorsement.